What now for Operation Grange?

The Complete Mystery of Madeleine McCann™ :: British Police / Government Interference :: 'Operation Grange' set up by ex-Prime Minister David Cameron

Page 1 of 1 • Share

What now for Operation Grange?

What now for Operation Grange?

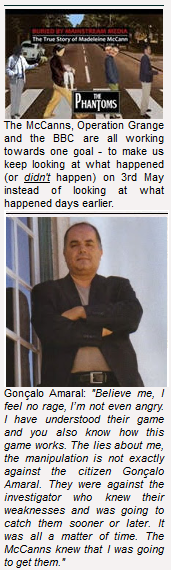

It looks as if Theresa May's days at no.10 are numbered, the Conservative party are on the brink of collapse and Labour are following suit - what does this mean for Operation Grange and the McCanns?

Grange was set up only because Rebekah Brooks threatened Theresa May with a week of bad headlines.

Has Brooks Made any further threats to Mrs May or to anyone else? Why is money constantly being thrown at this charade?

We saw similar traits with the McCanns paying Bell Pottinger £500,000 to keep them in the press. Have they made anymore such payments to anyone?

But, with May no longer at no.10 and a change of Government, will Grange continue? Will McCann support continue?

If Brooks is continuing with her threats, who will she blackmail? Will she get away with it?

Could this be the end?

Grange was set up only because Rebekah Brooks threatened Theresa May with a week of bad headlines.

Has Brooks Made any further threats to Mrs May or to anyone else? Why is money constantly being thrown at this charade?

We saw similar traits with the McCanns paying Bell Pottinger £500,000 to keep them in the press. Have they made anymore such payments to anyone?

But, with May no longer at no.10 and a change of Government, will Grange continue? Will McCann support continue?

If Brooks is continuing with her threats, who will she blackmail? Will she get away with it?

Could this be the end?

Re: What now for Operation Grange?

Re: What now for Operation Grange?

Frankly I don't believe a change in administration will make the slightest bit of difference.

Whatever it is that's being so strenuously protected, extends way beyond specific government individuals. It can only be a syndicate and syndicates of this nature aren't so easily dismantled.

As fast as a hole appears it's plugged. It's not difficult to catch a criminal, or a small group of criminals but try to expose a multi-national criminal force and you're looking for trouble.

Look what happened to poor old Dr David Kelly - and he's just one of many who died under mysterious circumstances in pursuit of truth.

Remember - there's no such thing as an honest politician, they all have skeletons hidden away.

Whatever it is that's being so strenuously protected, extends way beyond specific government individuals. It can only be a syndicate and syndicates of this nature aren't so easily dismantled.

As fast as a hole appears it's plugged. It's not difficult to catch a criminal, or a small group of criminals but try to expose a multi-national criminal force and you're looking for trouble.

Look what happened to poor old Dr David Kelly - and he's just one of many who died under mysterious circumstances in pursuit of truth.

Remember - there's no such thing as an honest politician, they all have skeletons hidden away.

Guest- Guest

Re: What now for Operation Grange?

Re: What now for Operation Grange?

Vanity Fair: Untangling Rebekah Brooks

January 2012

Rebekah Brooks was running the News of the World at 31, and Rupert Murdoch’s entire British newspaper empire at 41. A virtual member of the Murdoch family, close to Prime Ministers Blair, Brown, and Cameron, she relished her power—until the phone-hacking scandal took her down. Talking to Brooks’s former colleagues and friends, Suzanna Andrews uncovers the woman wrapped in the enigma, the keys to her meteoric rise, and the latest object of her incandescent ambition.

n the days after the June 2009 wedding party that took place at the 284-acre Sarsden estate, 75 miles northwest of London in the Oxfordshire countryside, it would be noted by the British press how remarkable it was, considering who the guests were, that the bride had managed to keep the event a secret from the media. There were no tabloid journalists hanging around the nearby village of Churchill, no paparazzi hiding in the bushes on the morning of June 13, the day Rebekah Wade, the editor of The Sun, Britain’s largest daily newspaper, celebrated her marriage to the former racehorse trainer and “international playboy” Charles Patrick Evelyn Brooks.

The prime minister, Gordon Brown, and his wife, Sarah, attended, as did David Cameron, the Conservative Party leader and prime minister–to–be, and his wife, Samantha. Rupert Murdoch, *The Sun’*s owner, had flown in. Murdoch’s daughter Elisabeth and her husband, the P.R. man Matthew Freud, who had helped to orchestrate the “media blackout,” had driven over from Burford Priory, their $7 million, 22-bedroom country home, 15 miles away. The guest list attested to the power Rebekah Wade had achieved, at the age of just 41, as the editor of The Sun, a tabloid with three million readers, and as the first woman to hold that job. But it also attested to her charm, “her warmth,” her “gregariousness,” and “her straightforward, sympathetic manner,” because the guests were also close friends. Sarah Brown had her for “sleepovers” at Chequers, the prime minister’s country retreat. David Cameron was so close he reportedly signed his letters to her “Love, David.”

That the media blackout had been so successful was even more surprising, considering that, by 2009, Wade had become something of a celebrity herself, with her first husband, Ross Kemp, a star of the hugely popular soap opera EastEnders, and then with Charlie Brooks. Endlessly written about and photographed—at Ascot, sitting in the royal box at Wimbledon, helicoptering to the Glastonbury Festival—she was instantly recognizable with her pile of red ringleted hair. In the competitive, ruthless, often cruel, and largely male culture of the British tabloids, Wade stood out. She spoke French, and had attended the Sorbonne; she and Charlie Brooks were at the center of the social scene in Chipping Norton—the weekend hub of the wealthy and powerful in Oxfordshire.

The wedding party at Sarsden’s lake—where, according to a friend, Brooks’s father had proposed to his mother—was, as one guest recalls, “incredibly romantic and lavish.” It was “all very Disney-esque, where everything looks right.” And at the time, everything was going right for Rebekah Wade—now Rebekah Brooks. In just 20 years she had gone from being a secretary at one of Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers to running his Sunday tabloid, the News of the World, at the age of 31, to running The Sun at 34. Her ambition had been described by the British media as “terrifying” and “phosphorescent,” but in her ascent up the ladder, it seemed she had never put a foot wrong. And just 10 days after her wedding party, she would climb even higher, when, on June 23, she was promoted to C.E.O. of News International, Murdoch’s newspaper empire in the U.K., which would make her one of the most powerful women in Britain.

As the 200 guests sipped champagne by the lake that day, few could imagine how fast Rebekah Brooks would fall. On July 15, 2011, two years after she became C.E.O., Brooks resigned. Two days later she was arrested “in connection with allegations of corruption and phone hacking” and interrogated by Scotland Yard detectives for nine hours before she was released on bail. Almost overnight—ever since it was revealed in early July that employees of the News of the World had hacked into the cell phone of Milly Dowler, a missing 13-year-old who was found murdered in 2002—Rebekah Brooks seemed to have become the most reviled woman in Britain, the woman at the center of what had begun as a phone-hacking scandal but has spread to include allegations of bribes to police, e-mail hacking, surveillance by private detectives of politicians and lawyers, and questions about a massive cover-up at News International. No charges have been filed against Brooks, and there have been no specific allegations of criminal wrongdoing against her, but the intensity of the anger toward Brooks has been accompanied by a growing number of questions as the judicial and parliamentary investigations have expanded and the extent of her influence has slowly emerged.

Brooks was the woman almost everybody had heard of, but about whom almost nothing was known. She rarely spoke in public or gave interviews, and when she did, she revealed nothing about herself. She was said to be closer to Rupert Murdoch than any of his six children, but of that relationship she never uttered a word, leaving it to Murdoch to raise questions about his own grip on reality in a remark he made on July 10. In an effort to stem the public rage, he had just shut the 168-year-old News of the World and put 280 people out of work. While walking with Brooks in Mayfair, he was asked by a reporter what his top priority was. Looking at Brooks with what seemed like deep affection, he answered, “This one.” It was a stupefying remark, but what Rebekah Brooks thought of it, no one could tell. She just smiled at the cameras, the cryptic Mona Lisa smile that could be seen in so many of her photographs—“as if she knows something she’s not telling,” says one journalist.

But that smile wasn’t on display on July 19 as Brooks told the parliamentary committee investigating the hacking scandal that she had never “condoned or sanctioned” hacking or even known that it was taking place at the News of the World while she was the editor. She said she had learned about the allegations that Milly Dowler’s phone had been hacked only when they were revealed in a story in The Guardian two weeks earlier. At the hearing she appeared exhausted, her trademark hair stringy and disheveled, but she testified calmly and coolly for nearly two hours. She said she had never met or had any dealings with Glenn Mulcaire, the private investigator whose files, seized by the police in 2006, would trigger the national scandal with some 11,000 pages of notes and 690 audiotapes, indicating that nearly 6,000 people—including politicians, celebrities, police officers, and crime victims—may have had their phones hacked by the News of the World.

Like Rupert Murdoch and his son James, who both testified before her that day, Brooks would say there were facts she could not recall, matters she could not discuss, issues for which she had not been responsible. But her testimony was more impressive—she didn’t fumble like Rupert Murdoch, showed none of the testy defensiveness of James. Some would say her testimony was “masterful” and “deft.” Critics would go so far as to suggest that she had hired a makeup artist in order to make her appear so wan and worn. “She looked so vulnerable,” says one prominent author. She was “amazing,” says a woman who has known Brooks for more than a decade. “Here she is, the most hated woman in Britain, on national television, and the only sign that she was nervous was that she blinked a little more than usual,” says this friend. “She is completely nerveless.” But her testimony would also raise a question: if she knew as little as she said she did, how had she risen to such power?

Road to Ambition

In the many press accounts of Brooks’s life there would be a number of facts on which everyone seemed to agree. She was born Rebekah Mary Wade in 1968 in Warrington, a town in the North of England situated between Liverpool and Manchester. She was an only child, and growing up she had lived in a tiny village south of Warrington.

She went to the area high school, Appleton Hall County Grammar, and studied French. She had been so passionate about becoming a journalist that when she was 14 she began to spend her weekends and school holidays at the local newspaper “making tea,” she once said, “and helping out.” Although she later attended the London College of Printing, after high school she took off for Paris, where she worked for a French architecture magazine.

Frequent mentions of her Sorbonne education would come later, after she became editor of The Sun, in 2003. One or two press stories over the years would note that Brooks appeared only to have taken a class at the Sorbonne, not studied for a degree. However, few questions were asked, even by her friends. “She never introduced us to people from her past,” says one. “That was a little creepy, as if there was no past.” Only recently did the media begin to focus on what the BBC referred to as her “startlingly brief and opaque” biography in Who’s Who. It was not that Brooks ever lied. She simply “allowed myths to grow and never challenged them,” says Roy Greenslade, the media commentator, who has known her for two decades.

Rebekah Wade was 20 years old in 1988 when she showed up at the Warrington office of The Post, a now defunct national tabloid. As Graham Ball, then the features editor, recalled to the BBC, she approached him and said, “I am going to come and work with you on the features desk as the features secretary or administrator.” He told her that would be impossible, as he was moving the next week to work in the paper’s London office. On the following Monday, he showed up at his new London office “and there she was.” As another editor recalled, she was a “skinny, hollow-eyed” young woman, who was “very, very, very ambitious,” and prepared to go to great lengths “to get on.”

In 1989, after The Post folded, Wade got a job as a secretary at the News of the World. She would soon move to the paper’s Sunday magazine, where she wrote for the TV soap-opera section. At some point Wade caught the eye of Piers Morgan, the editor of the News of the World, and now the host of CNN’s Piers Morgan Tonight. In his 2005 book The Insider, he would recount with gusto the thoroughness with which Wade arranged to bug a hotel room in advance of a 1994 meeting between the paper’s editors and Princess Diana’s lover, James Hewitt. Taken with Wade, Morgan promoted her rapidly—too rapidly, some say. By 1995, when he left to become editor of the Daily Mirror, the 27-year-old Wade was the deputy editor of the News of the World.

Paul McMullan first met Wade in 1994, when she was still features editor. McMullan recalls how inexperienced she was. “She’d never done an investigation or written a news story,” he says, and she had little understanding of what went into the reporting of one. A former deputy to Wade, he is today a central figure in the hacking scandal, one of the few journalists to not only publicly admit that hacking was widely practiced but also to defend it. “I think you can do anything to get at the truth,” McMullan says. “The criticism is we did it so badly and so often under her stewardship it became ridiculous.” In the 90s, though, outright phone hacking was not that prevalent. Before digital-cell-phone technology became common, listening in on cell-phone conversations was done with scanners. It was, McMullan has said, why it was so easy for reporters to listen in on Princess Diana’s phone calls, for example. Just as widespread among newspapers, he says, was the use of private investigators to get unpublished phone numbers and addresses—and sometimes for such other “dark arts” as getting medical and financial records, and for surveillance.

McMullan says that Wade knew about the use of private investigators—“Impossible not to,” he says. “I was deputy features editor. I ran the same department that she did, and every week we’d see the bills from the private investigators: £2,000, £4,000.” However, he can’t be sure she always knew what they were doing.

“She was quite sweet in those days,” says McMullan. “She knew she was out of her depth and would rely on other people to make her shine. And, funnily enough, it was because she was so hopeless, we wanted to protect her as our boss when we would find out she didn’t know what she was doing,” he recalls. “So that worked, as one management style, if you like.”

“She’d get you to do things,” says another former News of the World reporter. “She had this charisma, this magnetic attraction,” he says. “She would praise to high heaven, make you feel like you were on top of the world. It was only afterwards that you realized you were manipulated.” In a largely male tabloid world—a business in which Brooks was once asked at a corporate golf gathering to sew a senior executive’s button back on his shirt, which she did—perceptions counted for a lot.

“She was very tactile, touching you on the arm, looking straight into your eyes as though there was no one more important in the room,” this former News reporter says. “From the way she acted, you would think she wanted to sleep with you.” But “no,” he says, “she didn’t want to sleep with the help; she was way too up the scale for that.”

She worked nonstop. “She was going at 150 all day,” this man recalls. “She was very intense. I thought she was a very insecure woman, actually, desperate for a lot of love and attention,” he says. “I was quite friendly with her at some point, as friendly as anyone can get with her, and in her quieter moments she would say, ‘No one loves me; I’m in a battle here.’ ” But even then, she was careful. Even out drinking after work, “she did not get pissed, ever. She never let her guard down,” and never spoke about her past. Like others, he wondered. “In the early days she used this accent, a girls’-school accent, meaning she’d been poshly educated, but every now and again the accent would slip and you’d realize: Oh, yeah.” There were rumors of a father who “was absent or who left,” of some kind of abandonment or “betrayal” that was felt deeply by her mother in particular, with whom Wade was, and still is, extremely close. But no one pressed.

Some believed her father was a vicar, or otherwise well-to-do, although, according to a copy of Brooks’s birth certificate, her father, John Robert Wade, was a tugboat deckhand. At some point, he became a gardener. In an interview with the BBC last summer, Brooks’s childhood friend Louise Weir would say that Brooks’s parents had a tree-pruning business that was so prosperous it afforded the family enviable vacations, and a personalized license plate for her mother, Deborah. When contacted, Weir was agitated, said she had been harassed by the media, and hung up the phone. But she told the BBC the Wades had been a churchgoing family. Rebekah, she said, was “a typical Gemini. She’s got her lovely fluffy side and her angry side She’s always been able to get what she wants out of people, even if they don’t really like her.”

In July 1996, a brief article appeared in the local Warrington Guardian. The occasion was Rebekah Wade’s engagement to Ross Kemp, whom she had met the year before at a golf tournament. The paper gushed about rumors that Wade’s engagement ring had cost $30,000. It also interviewed her father. John Wade was still living in Hatton, the small village where he and his then wife Deborah had been living when their daughter, Rebekah, was born. He said that he had no idea who Ross Kemp was, because he rarely watched television. However, he was “looking forward” to having Kemp visit him and his wife, Barbara, whom he’d married when Rebekah was 20. “The first time I knew of the engagement was when Rebekah rang to tell me she was getting married. It was quite a surprise,” he told the paper. Six weeks later, in September 1996, Wade died, at the age of 50. According to his death certificate, the cause was cirrhosis of the liver, so severe it had led to hepatic failure.

The Fantasy Daughter

When people who know Rupert Murdoch speak of his feelings for Rebekah Brooks, they use very emotional language: He “adores her,” “is devoted to her,” “is besotted with her.” The affection is clear in video clips and photographs of the two of them together—smiling into each other’s eyes, his arm around her, Brooks leaning in toward him. By most accounts, Rebekah Wade met Rupert Murdoch sometime in the mid-1990s, but it was not until the beginning of 1998 that people began to remark at how close they had become.

That January, Wade left the News of the World to become deputy editor of The Sun. It was a huge promotion—made by Murdoch despite the qualms of *The Sun’*s editor, Stuart Higgins. And almost from the moment she got that job, it was obvious to many that the job she wanted next was Higgins’s. Indeed, in May of that year Alastair Campbell, then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s press secretary, wrote in his diary—which was later published as Power & the People—of an “odd” party that Wade gave at the Belvedere, in Holland Park, “where you felt Stuart was being prepared for departure and her for his job.” But the following month the editorship of The Sunwent instead to David Yelland, the deputy editor of the New York Post. Although, as one former Blair adviser recalls, “she is too clever to have allowed herself to look insubordinate,” it was an open secret that she disliked Yelland, whose life, one News International executive recalls, “was made sort of miserable.” Two years later, in 2000, Murdoch once again promoted Wade. In a move that still baffles people, he suddenly fired Phil Hall, the respected editor of the News of the World, and gave his job to Wade. In 2003, when David Yelland resigned from The Sun, Murdoch installed Wade as the paper’s editor—the job, she would tell the staff on her first day, she had “dreamed of” ever since she was a child.

Although Murdoch has four daughters, two of them grown, over the years he has seemed closer to Brooks than to any of them. She was, people say, like the fantasy daughter, the daughter he always wished he had—the one who never argued with him, who devoted her life to pleasing him. They reportedly swim together in the mornings when he is in London. She fusses over him at dinner parties—making sure he’s eating, that his wineglass is full. “She’s very attentive,” says one News International executive.

“When she wants someone, she will woo them so intensely—there will be invitations, the sharing of confidences,” says a former friend. “She wraps herself around you.” Much as she apparently learned to play golf because one of her bosses did, she learned to sail because Murdoch enjoyed sailing, as does his family, including his older son, Lachlan, on whose yacht Rebekah reportedly spent the New Year’s holiday in 2002.

“It isn’t just Rupert who is in love with her; it’s also James and the family,” says one former News Corp. executive who has known the Murdochs for decades. While her relationship with Murdoch’s younger son, James, became closer in late 2007, when he was put in charge of News International, Wade had been friends with Elisabeth for more than a decade. In 2001, she was not only a guest at Elisabeth’s wedding to Matthew Freud, but among a select group invited to her bridal shower. The two spent weekends together in Chipping Norton. “They were all over each other in the country,” says a friend. In many ways, Brooks had become a member of the Murdoch family, which, says one Murdoch executive, “has been key in her rise.”

If to some in the Murdoch empire she was “the impostor daughter,” Brooks did share, more than any of his actual children, one of Murdoch’s great passions. “She was the one who expressed his love for newspapers,” says one newspaper executive. While many at News Corp. would be happy to sell the newspapers, says one former executive, and Murdoch’s children have not appeared to share his enthusiasm for the business, Brooks was as passionate about newspapers as Murdoch. He saw her as a “great campaigning editor.” Indeed, he supported one of her most controversial campaigns, the 2000 “Name & Shame” series for the News of the World, which was prompted by the murder of eight-year-old Sarah Payne by a registered sex offender. For two weeks, she published photographs, names, and the whereabouts of convicted pedophiles. In the process, she became very close to the child’s mother, Sara Payne, at one point giving her a company cell phone, which, according to investigators, may have been hacked, an allegation that Brooks said was “abhorrent.”

Murdoch loved Rebekah Wade’s “fantastic drive,” says one executive. More than anything, he loved the fact that her whole life was wrapped up in his beloved papers; when she was scooped by a rival, she could go into dark funks, so much so that on one occasion, when she was beaten to a story by the Mirror, Murdoch reportedly called Les Hinton, who at the time was the executive in charge of the U.K. newspaper business, to ask, “Is she all right?”

And at every turn, she gave him the papers he wanted. A co-founder of Women in Journalism, an organization to help promote women’s careers in the field, Wade—along with Murdoch’s former wife Anna—was reported to be personally offended by *The Sun’*s “Page 3,” which daily features photographs of bare-breasted women. But they were what Murdoch wanted, and so she continued to run the photos, and defended them roundly. In 2004, in response to criticisms of “Page 3” from Clare Short, a former Cabinet minister, Wade ran a “Hands Off Page 3” campaign which included running a photograph of Short’s head on a flabby, naked female body, and describing Short as “fat,” “ugly,” “short on looks,” and “short on brains.”

The Power and the Story

That July, six months after her savaging of Clare Short, Wade threw a 40th-birthday party for Ross Kemp. Cherie Blair came, as did Gordon Brown, then chancellor of the Exchequer, along with David Blunkett, the home secretary, and Lord Stevens, then chief of Scotland Yard. The star of Britain’s most popular television soap, Kemp was a big celebrity, and her relationship with him had helped catapult Wade into the limelight. But they had not come because of Kemp; the power now was hers—courtesy of Rupert Murdoch. At the News of the World and The Sun she ran not only two of Britain’s biggest newspapers but also ones that could, and did, destroy people’s lives and careers, frequently with a political agenda devoted to advancing Murdoch’s interests in Britain—particularly his profitable satellite-television business. The threat was always implicit: Stand in Murdoch’s way and the papers will retaliate. “Everybody was afraid,” says one prominent newspaper editor. To many it was “just a fact of life,” says this editor, “that you had to give in to them.” It was a fear that would reach into the highest levels of British politics, and among his many editors, none would be perceived as a more enthusiastic political partner to Murdoch than Wade.

She was not known to have strong political opinions. “Rebekah wore her politics lightly,” says one man, who adds that in the 15 years he has known her “I never heard her offer an opinion about anything in politics. She was interested in power.” And, it seemed, enjoyed wielding it.

She had gotten her first political toehold through Tony Blair—the prime minister now regarded as perhaps the most obsequious in his relationship to Murdoch. Wade met Blair through Kemp, who was a major Labour Party supporter and fund-raiser, but it was Alastair Campbell, an old friend of hers from his days as a tabloid journalist, who would really open doors to Downing Street for her. “The relationship between Alastair and Rebekah was a singularly close one,” recalls Lance Price, a former Blair spokesperson. Although she was just the deputy editor of the News of the World in 1997 when Blair was elected, largely because of Campbell, she had special access.

Wade became close to Blair and to his wife, Cherie—a “friendship” that would cool but continue even after the police discovered in 2002 that News reporters were planning to set Cherie up by taping a conversation between her and the boyfriend of her “life coach.” He had helped find the Blairs’ eldest son an apartment at a reduced price—an apparent favor to the prime minister, it eventually became a major story. The News would lambaste Cherie as “foolish” and “arrogant,” but Wade’s dinners and meetings with Tony Blair continued, perhaps encouraged by an editorial that appeared during her first week as editor of The Sun, a month after the swipe at his wife: “New Labour have had a good run for their money—your money, actually. But it’s time to say we’re very disappointed.” The Sun did not withdraw its backing for Blair; it was just a little reminder of who buttered his bread.

In a remarkable feat of social and emotional gymnastics, Wade would also become friendly with Gordon Brown. As chancellor of the Exchequer before he became prime minister, in 2007, Brown had a famously touchy relationship with Blair—which, according to Lord John Prescott, Wade deftly mined.

Deputy prime minister at the time, Prescott now recalls how “Rebekah Wade used to have dinner with Blair and Brown and play them off against each other.” He is still shocked at how easy it was. “If Blair wanted to know what Brown was doing, she’d fix the dinner up and then tell him,” he recalls. “They used to use her for intelligence on the other.” It was artful, he says, the way she made each man think that she was on his side. “I used to say, ‘Why are you listening to that bloody woman?’ It was all about Murdoch,” says Prescott, who is among the politicians who were hacked by the News—in his case, in 2006, following the exposure of an extramarital affair with his secretary.

As she did with Cherie Blair, Wade also became very close to Sarah Brown. It was something people would note—the intimacy of her friendships with the powerful as she befriended their husbands, wives, and children. That was “the nature of how she operates,” says Roy Greenslade. “She gets that close to people. It’s not simply a business thing—it’s a personal thing. It’s domestic.” But Wade’s friendship with the Browns did not stop her, in the fall of 2006, from phoning them with upsetting news. The Sun had discovered from an informant that the Browns’ infant son had cystic fibrosis, and the paper was going to run the story the next day. Which it did, on the cover, with the screaming headline chancellor’s baby has cystic fibrosis. The Browns, who had already lost a baby daughter and were still coming to terms with the news of their son’s illness, were devastated. It is this story—along with the revelation that Gordon Brown’s phone may have been hacked by the News of the World and his financial records accessed by Murdoch’s Sunday Times—that today particularly horrifies people. “If that doesn’t make your skin crawl, the evilness of it, what does?” says a Murdoch observer. It was a measure of Murdoch’s political power, and Rebekah Wade’s, that Gordon Brown was among the guests at her wedding three years later.

Not that this bit of fealty made any difference. That September, on the day Brown was to make a major speech, The Sun’s headline would read: labour’s lost it. *The Sun’*s sudden switch of allegiance from the Labour Party to David Cameron’s Conservatives shocked the British political establishment. To some, it was a typically cynical Murdochian move of backing the likely winner, but by then Brooks had also grown very close to Cameron, according to a friend of both Brooks’s and Cameron’s. Her deputy—then successor—at the News, and her close friend, Andy Coulson, had gone to work as Cameron’s media adviser after resigning from the News in 2007 following the hacking convictions of the paper’s royals editor, Clive Goodman, and the private investigator Glenn Mulcaire. The Conservative leader was also Brooks’s neighbor in Oxfordshire, and Charlie Brooks had gone to Eton with Cameron’s brother. Cameron dined at the Brooks’s home on weekends. And he was a guest at the annual New Year’s Eve bash, thrown by the Brookses with several other couples from the Oxfordshire set.

Within a week of Cameron’s election, in May 2010, Rupert Murdoch paid a visit to 10 Downing Street for a private meeting with the new prime minister. In July he visited again, shortly after his company made its bid to control BSkyB. What they discussed is anybody’s guess, but that same month Cameron’s administration criticized the BBC—the chief competitor to Murdoch’s BSkyB and a longtime Murdoch bête noire—for “extraordinary and outrageous” waste and proposed reducing its budget.

Absence and Malice

In the spring of 2009, Wade divorced Kemp. They had been separated for nearly two and a half years. In court papers, Kemp reportedly admitted to infidelity. “The relationship with Ross was very stressful,” says a friend. The tensions had briefly made headlines in 2005—and caused much giggling in London—when Rebekah was arrested at four in the morning for assaulting Kemp and giving him a fat lip. No charges were filed, and, as the press reported, she emerged from an eight-hour stint in jail and went straight to the office—wearing a designer suit Rupert Murdoch had sent to the police station.

By then, Wade’s relationship with Murdoch had become “an issue,” says one executive. “She could say and do what she liked,” this person says. As she rose up the ranks, she had become increasingly imperious. She could be rude and abrasive, in one instance reportedly throwing an ashtray at the staff on the newsdesk when a rival paper scooped them. “She was intimidating,” says this executive. “She deeply resented certain people and was ruthless,” says another, who recalls being warned by his boss “not to cross Rebekah.” As far back as 2001, “the power had gone to her head,” says Paul McMullan, who resigned from the News of the World late that year. “She became Cruella de Vil. I didn’t need that.”

What many former staffers now say is that, under Wade, the pressures on the newsroom were intense, particularly at the News. As her deputy, Andy Coulson was as driven and competitive as she was, and he set the pace of the office even while Wade was editor. Unlike most tabloid editors, who constantly roamed their newsrooms, she was frequently away, meeting and dining with politicians and other influential people. One of her dinner partners, according to a former police investigator, was John Yates, the senior Scotland Yard official who was forced to resign last summer, in large part due to the fact that, in 2009, he told Parliament that there was no evidence of widespread hacking by the News in the files seized from Mulcaire—the same files that investigators for a judicial-review committee recently determined contained evidence that the phones of 5,795 people may have been hacked by some 28 News employees.

Wade’s absence from the newsroom may have set up a situation where things could occur that she didn’t know about. She was on vacation in April 2002 when the News of the World published the first story that referenced messages that had been left on Milly Dowler’s cell phone. The story was quickly pulled and re-written, which is why many people didn’t notice it then—including Brooks, who told Parliament in July that vetting the story’s sourcing would have been the responsibility of her subordinates. Paul McMullan, who was covering the Dowler story for the Sunday Express, is among those who believe that Brooks was probably accurate on this point. “I don’t think they’d have bothered telling her, ‘This is where we got it from.’ ” Roy Greenslade says it is “possible that, although she should have known [that hacking was going on], she genuinely didn’t know, because I don’t think she knew how stories arrived most of the time.” Or what her staff was doing.

Today, the accusations against News International go way beyond anything that Brooks would have had responsibility for as the editor of The Sun and the News of the World. As of mid-December, 19 people have been arrested, nearly all in connection with allegations of either hacking, bribes paid to police, or both. Among those was Andy Coulson, who was forced to resign from Cameron’s government in January 2011. In recent public testimony Paul McMullan alleged that Coulson not only knew about phone hacking but “brought the practice wholesale with him when he became deputy editor” of the News, and called Brooks and Coulson “the scum of journalism.” Politicians and lawyers investigating News International describe a company whose entire culture may have been corrupted by an ingrained sense that they were above the law, that they could get away with anything. Which made believable recent testimony by the singer Charlotte Church that—despite the denials of her agent that she was offered a fee—when she was 13, she gave up $159,000 for performing at Murdoch’s 1999 wedding to Wendi Deng in expectation of favorable treatment by his papers. And yet, his tabloids would hound Church and her family, to the point that, she said, her mother attempted suicide. Among the harshest characterizations would come from the Labour M.P. Tom Watson, one of Murdoch’s leading critics, who in a November parliamentary hearing referred to News International as “a criminal enterprise.”

But if Brooks didn’t know about the alleged wrongdoing when it occurred, her elevation in June 2009 to C.E.O. put her in the position, many believe, where, if she didn’t know then, she should have.

That June, though, it seemed as though everything had come together perfectly for Brooks. In the 18 months since James Murdoch had taken the helm at News International, she had made herself as indispensable to him as she had to his father, and, with Rupert Murdoch’s blessing, James had rewarded her with the promotion to C.E.O. On the personal front as well, she was said by friends to be “blissful” in her relationship with Charlie Brooks. If Kemp, as one friend says, had been “the perfect husband for a tabloid editor,” Brooks was “the perfect husband for a C.E.O.” Although his family was not as wealthy as it had once been, the Brookses were genuinely “posh,” listed in Burke’s Peerage and said to be descendants of the 14th-century king Edward III.

Five years older than Wade, Brooks, now 48, had never been married when the two met at the Chipping Norton home of a mutual friend. They began seeing each other in early 2007. Warm, easygoing, and unambitious, Brooks was, according to friends, Wade’s opposite, and a perfect foil for her intensity. He’d been a racehorse trainer, dabbled in sports marketing, and run a mail-order sex-toy company. He had also tried his hand at writing, and in April 2009 came out with his first novel, Citizen, which was published by Rupert Murdoch’s HarperCollins.

Brooks, friends say, was devoted to Wade. And she to him. She was stunned, one friend recalls, when Brooks handed her his BlackBerry one day, and asked her to see if the tech specialists at News International could repair it. “She felt quite fantastic to have somebody who had no secrets,” says this friend, “someone she could trust completely” and “somebody who trusted her.” People were surprised when Wade took Brooks’s name after their wedding—something she had not done during her marriage to Kemp. Overnight, Rebekah Wade was gone, replaced by “Mrs. Brooks.”

The first sign of trouble came four weeks after her wedding. On July 8, The Guardian revealed that News International had made payments of more than $2 million to several people to settle claims that their phones had been hacked—including Gordon Taylor, the head of the football players’ union. It was the first public indication that the hacking had gone beyond one “rogue” reporter, as News International had referred to Clive Goodman, the former royals editor, who had been convicted of hacking the phones of members of the royal family. In a letter to Parliament, Brooks took issue with that story and other revelations in The Guardian, which, she wrote, “has substantially and likely deliberately misled the British public.”

During the next two years she would staunchly defend News International. When Parliament invited her to testify in late 2009, she declined. Even after it issued a report in early 2010 assailing News International executives for their “collective amnesia” in their repeated denials of widespread hacking, she stood firm. She revealed nothing about the growing tensions within News International, particularly as the relationship between Rupert and James began to fray. Described by sources close to the Murdochs as the “go-between” in an increasingly fraught father-son relationship, Brooks was now under pressure to please and protect not only Rupert but also James, who had both taken the position that they had no idea what was going on inside their company, and particularly James, passing blame on to subordinates.

Family Affair

In May 2010, according to testimony by James, News International’s chief attorney, Tom Crone, authorized the use of a private investigator to follow Mark Lewis and Charlotte Harris, two lawyers who represented the growing number of hacking victims who were suing the company— Lewis going on to represent Milly Dowler’s parents. The surveillance was part of an effort to get dirt on the lawyers’ private lives. Although Brooks is said to have been close to Crone, and he reported directly to her, there has been no suggestion that she knew about this—or about the surveillance of News International’s big critic, the Labour M.P. Tom Watson, which took place in the fall of 2009.

But she appears to have known, as far back as 2006, that the hacking at the News of the World went beyond one “rogue” reporter who covered the royal family. As she told Parliament in July, that was when the police informed her that as editor of The Sun she, too, had been hacked by the News, a fact she said she relayed to News International executives at the time.

By February 2010, Brooks may have understood that the hacking was even more widespread. That month she quietly arranged a $1 million payout to Max Clifford, a veteran London P.R. agent who was suing News International for hacking—not only putting an end to his lawsuit against the company, but also preventing the public disclosure, ordered by a judge, of evidence of more extensive hacking.

Recently, Neville Thurlbeck, one of the News reporters implicated in the hacking scandal, said that in July 2009 he had prepared “a dossier” which implicated “an executive.” He claimed he had tried to get the file to James Murdoch and to Brooks but was rebuffed by people close to them. “I had a warm and trusting relationship with Rebekah,” he wrote in an article for the Press Gazette in November, blaming himself for not trying harder to get his dossier to Brooks. If this account is accurate, then—considering Thurlbeck’s key role in the hacking scandal and the investigations—what is striking is that Brooks does not appear to have ever spoken to him.

She does, however, appear to have spoken to a Scotland Yard detective chief superintendent named David Cook. Although she would tell Parliament in July that she did not recall the meeting, it seems from published reports and interviews with Cook himself and his attorney, Mark Lewis, that the meeting took place in early January 2003. Cook was the lead investigator in a brutal unsolved murder of a private investigator who had been found with an ax in his head in 1987. Cook had asked for the meeting because, several months earlier, his family had been followed and photographed by people hired by the News of the World. Cook’s mail had also been tampered with. The police investigation had allegedly found evidence that the surveillance had been ordered by one of the News’s top editors, Alex Marunchak, as a favor to two of the suspects in the case: Jonathan Rees and Sid Fillery, private investigators whose firm, Southern Investigations, had worked for the News.

The firm also did work for numerous media outlets, and the meeting shines a light on the questions that have been raised today, both in Parliament and in a government judicial review, about the practices and ethics of the British press in general. There is no evidence that Brooks had any prior knowledge of what was going on, but the police suspected that “News of the World staff were guilty of interference and party to using unlawful means to attempt to discredit a police officer and his wife,” according to the M.P. Tom Watson.

When Brooks heard from Cook about the surveillance, her response, Cook says, was that she had no idea that it had gone on, but if so it was “in the public interest”—a common justification used by the media in Britain for many of the more questionable reporting practices and privacy intrusions. This, she said, was because Cook was rumored to be having an affair with a television personality, a remarkable response considering that the woman, Jacqui Hames, was Cook’s wife.

Brooks also told Parliament in July that she had not heard of the private investigator Jonathan Rees until a few months earlier. “She sat there in front of that parliamentary committee and said she couldn’t remember what happened,” says Cook, who insists that during his 2003 meeting with Brooks he specifically mentioned Jonathan Rees. He also says that he read her a witness statement that alleged that in the late 80s—before Brooks worked at News International—Southern Investigations had paid some of Alex Marunchak’s credit-card bills and the school tuition for one of his children. According to Cook, Brooks “became very defensive about Marunchak, saying how since he’d moved to the Irish desk, sales there had gone up and he was doing such a great job.” Cook says he was stunned, but he didn’t press any further. He recalls “being told beforehand by a senior officer, ‘Remember, she is very close to Sir John Stevens,’ ” then the head of Scotland Yard. “I took that as a warning,” says Cook.

What Brooks did next isn’t clear. In September, Tom Crone, the top lawyer at News International, told Parliament that he was never aware of the surveillance of David Cook, which would suggest that she did not inform her legal manager about the meeting. There does not appear to have been any reaction at the News of the World. Marunchak remained at the paper until 2006. Jonathan Rees was rehired by the News in 2005 when he was released from prison after serving time for planting cocaine on a client’s wife. And recently Cook learned that his phone had been hacked by Glenn Mulcaire, who allegedly may have also been commissioned by one of Brooks’s editors to search his financial records.

Rebekah Brooks may have simply forgotten the meeting. Just five days after it took place, she left the News of the World to become the editor of The Sun, the job she’d wanted so badly. In all the excitement of ambition rewarded, her interest in the murky activities of her staff may have waned.

Right to the end, Rupert Murdoch stood by her. It was only under “intense pressure,” says a family confidante, that he finally caved in and accepted her resignation on July 15, reportedly telling her to just take a “leave, travel around the world.” As it was, her severance of $2.7 million would cause yet more ire, along with the fact that she still has her chauffeur-driven Mercedes, courtesy of News International, along with an office in downtown London. If she was the perfect daughter, Murdoch was the perfect father. But his loyalty to Brooks, and that of his family—James in particular, who finds himself under increasing scrutiny—will be tested as the investigation, which seems to yield new revelations daily, intensifies.

Off to the Races

For Brooks, there was a brief period of depression in the wake of the arrest, friends say, a spell of humiliation, when she refused invitations and remained almost secluded at her home in Oxfordshire, venturing out only with her trademark hair rolled into a bun so people wouldn’t recognize her. But that flirtation with pain and the possibility of failure may be ending. In late November, Brooks was photographed—holding a copy of The Sun, no less—at the Newbury races with Charlie, who has recently announced his return to the horse-training business. And she has re-appeared on the dinner circuit, where, if the hacking scandal is mentioned, Brooks is now among the “victims”—obviously, says one loyal friend, “because she was hacked more than anybody else.” And there are signs that she will soon be emerging publicly in a philanthropic role, as suggested by a story that made its way into the British papers in November about her lunch at Boisdale, in Belgravia, with General Sir Mike Jackson, the former head of the British military, to discuss plans for a February charity event.

But she’s not off the hook yet. There may be more inquiries and litigation ahead, and Brooks is still awaiting the outcome of the police investigation, which will determine whether or not criminal charges will be brought against her. Last month, Scotland Yard significantly lowered its victim estimates, announcing that it believed only about 800 people had actually been hacked. The other 5,000 names in Glenn Mulcaire’s notebook were, it said, “potential targets” and are “unlikely to have been hacked.” But there’s still the mystery of the laptop and iPad, found in the trash in a parking garage near her home the day after she was arrested. Charlie Brooks said they were his, yet five months later, the police had still refused to release them.

And then there is the baby. As her public-relations firm, Bell Pottinger, announced recently, Rebekah and Charlie Brooks are to be the proud parents of a baby girl, due next month via a surrogate mother, rumored to be a relative. Some critics question the timing of the annoucement, seeing it as a bid by Rebekah Brooks to gain sympathy, but they are being churlish. Having a baby, friends say, has, like having the editorship of The Sun, long been one of her ambitions.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

January 2012

Rebekah Brooks was running the News of the World at 31, and Rupert Murdoch’s entire British newspaper empire at 41. A virtual member of the Murdoch family, close to Prime Ministers Blair, Brown, and Cameron, she relished her power—until the phone-hacking scandal took her down. Talking to Brooks’s former colleagues and friends, Suzanna Andrews uncovers the woman wrapped in the enigma, the keys to her meteoric rise, and the latest object of her incandescent ambition.

n the days after the June 2009 wedding party that took place at the 284-acre Sarsden estate, 75 miles northwest of London in the Oxfordshire countryside, it would be noted by the British press how remarkable it was, considering who the guests were, that the bride had managed to keep the event a secret from the media. There were no tabloid journalists hanging around the nearby village of Churchill, no paparazzi hiding in the bushes on the morning of June 13, the day Rebekah Wade, the editor of The Sun, Britain’s largest daily newspaper, celebrated her marriage to the former racehorse trainer and “international playboy” Charles Patrick Evelyn Brooks.

The prime minister, Gordon Brown, and his wife, Sarah, attended, as did David Cameron, the Conservative Party leader and prime minister–to–be, and his wife, Samantha. Rupert Murdoch, *The Sun’*s owner, had flown in. Murdoch’s daughter Elisabeth and her husband, the P.R. man Matthew Freud, who had helped to orchestrate the “media blackout,” had driven over from Burford Priory, their $7 million, 22-bedroom country home, 15 miles away. The guest list attested to the power Rebekah Wade had achieved, at the age of just 41, as the editor of The Sun, a tabloid with three million readers, and as the first woman to hold that job. But it also attested to her charm, “her warmth,” her “gregariousness,” and “her straightforward, sympathetic manner,” because the guests were also close friends. Sarah Brown had her for “sleepovers” at Chequers, the prime minister’s country retreat. David Cameron was so close he reportedly signed his letters to her “Love, David.”

That the media blackout had been so successful was even more surprising, considering that, by 2009, Wade had become something of a celebrity herself, with her first husband, Ross Kemp, a star of the hugely popular soap opera EastEnders, and then with Charlie Brooks. Endlessly written about and photographed—at Ascot, sitting in the royal box at Wimbledon, helicoptering to the Glastonbury Festival—she was instantly recognizable with her pile of red ringleted hair. In the competitive, ruthless, often cruel, and largely male culture of the British tabloids, Wade stood out. She spoke French, and had attended the Sorbonne; she and Charlie Brooks were at the center of the social scene in Chipping Norton—the weekend hub of the wealthy and powerful in Oxfordshire.

The wedding party at Sarsden’s lake—where, according to a friend, Brooks’s father had proposed to his mother—was, as one guest recalls, “incredibly romantic and lavish.” It was “all very Disney-esque, where everything looks right.” And at the time, everything was going right for Rebekah Wade—now Rebekah Brooks. In just 20 years she had gone from being a secretary at one of Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers to running his Sunday tabloid, the News of the World, at the age of 31, to running The Sun at 34. Her ambition had been described by the British media as “terrifying” and “phosphorescent,” but in her ascent up the ladder, it seemed she had never put a foot wrong. And just 10 days after her wedding party, she would climb even higher, when, on June 23, she was promoted to C.E.O. of News International, Murdoch’s newspaper empire in the U.K., which would make her one of the most powerful women in Britain.

As the 200 guests sipped champagne by the lake that day, few could imagine how fast Rebekah Brooks would fall. On July 15, 2011, two years after she became C.E.O., Brooks resigned. Two days later she was arrested “in connection with allegations of corruption and phone hacking” and interrogated by Scotland Yard detectives for nine hours before she was released on bail. Almost overnight—ever since it was revealed in early July that employees of the News of the World had hacked into the cell phone of Milly Dowler, a missing 13-year-old who was found murdered in 2002—Rebekah Brooks seemed to have become the most reviled woman in Britain, the woman at the center of what had begun as a phone-hacking scandal but has spread to include allegations of bribes to police, e-mail hacking, surveillance by private detectives of politicians and lawyers, and questions about a massive cover-up at News International. No charges have been filed against Brooks, and there have been no specific allegations of criminal wrongdoing against her, but the intensity of the anger toward Brooks has been accompanied by a growing number of questions as the judicial and parliamentary investigations have expanded and the extent of her influence has slowly emerged.

Brooks was the woman almost everybody had heard of, but about whom almost nothing was known. She rarely spoke in public or gave interviews, and when she did, she revealed nothing about herself. She was said to be closer to Rupert Murdoch than any of his six children, but of that relationship she never uttered a word, leaving it to Murdoch to raise questions about his own grip on reality in a remark he made on July 10. In an effort to stem the public rage, he had just shut the 168-year-old News of the World and put 280 people out of work. While walking with Brooks in Mayfair, he was asked by a reporter what his top priority was. Looking at Brooks with what seemed like deep affection, he answered, “This one.” It was a stupefying remark, but what Rebekah Brooks thought of it, no one could tell. She just smiled at the cameras, the cryptic Mona Lisa smile that could be seen in so many of her photographs—“as if she knows something she’s not telling,” says one journalist.

But that smile wasn’t on display on July 19 as Brooks told the parliamentary committee investigating the hacking scandal that she had never “condoned or sanctioned” hacking or even known that it was taking place at the News of the World while she was the editor. She said she had learned about the allegations that Milly Dowler’s phone had been hacked only when they were revealed in a story in The Guardian two weeks earlier. At the hearing she appeared exhausted, her trademark hair stringy and disheveled, but she testified calmly and coolly for nearly two hours. She said she had never met or had any dealings with Glenn Mulcaire, the private investigator whose files, seized by the police in 2006, would trigger the national scandal with some 11,000 pages of notes and 690 audiotapes, indicating that nearly 6,000 people—including politicians, celebrities, police officers, and crime victims—may have had their phones hacked by the News of the World.

Like Rupert Murdoch and his son James, who both testified before her that day, Brooks would say there were facts she could not recall, matters she could not discuss, issues for which she had not been responsible. But her testimony was more impressive—she didn’t fumble like Rupert Murdoch, showed none of the testy defensiveness of James. Some would say her testimony was “masterful” and “deft.” Critics would go so far as to suggest that she had hired a makeup artist in order to make her appear so wan and worn. “She looked so vulnerable,” says one prominent author. She was “amazing,” says a woman who has known Brooks for more than a decade. “Here she is, the most hated woman in Britain, on national television, and the only sign that she was nervous was that she blinked a little more than usual,” says this friend. “She is completely nerveless.” But her testimony would also raise a question: if she knew as little as she said she did, how had she risen to such power?

Road to Ambition

In the many press accounts of Brooks’s life there would be a number of facts on which everyone seemed to agree. She was born Rebekah Mary Wade in 1968 in Warrington, a town in the North of England situated between Liverpool and Manchester. She was an only child, and growing up she had lived in a tiny village south of Warrington.

She went to the area high school, Appleton Hall County Grammar, and studied French. She had been so passionate about becoming a journalist that when she was 14 she began to spend her weekends and school holidays at the local newspaper “making tea,” she once said, “and helping out.” Although she later attended the London College of Printing, after high school she took off for Paris, where she worked for a French architecture magazine.

Frequent mentions of her Sorbonne education would come later, after she became editor of The Sun, in 2003. One or two press stories over the years would note that Brooks appeared only to have taken a class at the Sorbonne, not studied for a degree. However, few questions were asked, even by her friends. “She never introduced us to people from her past,” says one. “That was a little creepy, as if there was no past.” Only recently did the media begin to focus on what the BBC referred to as her “startlingly brief and opaque” biography in Who’s Who. It was not that Brooks ever lied. She simply “allowed myths to grow and never challenged them,” says Roy Greenslade, the media commentator, who has known her for two decades.

Rebekah Wade was 20 years old in 1988 when she showed up at the Warrington office of The Post, a now defunct national tabloid. As Graham Ball, then the features editor, recalled to the BBC, she approached him and said, “I am going to come and work with you on the features desk as the features secretary or administrator.” He told her that would be impossible, as he was moving the next week to work in the paper’s London office. On the following Monday, he showed up at his new London office “and there she was.” As another editor recalled, she was a “skinny, hollow-eyed” young woman, who was “very, very, very ambitious,” and prepared to go to great lengths “to get on.”

In 1989, after The Post folded, Wade got a job as a secretary at the News of the World. She would soon move to the paper’s Sunday magazine, where she wrote for the TV soap-opera section. At some point Wade caught the eye of Piers Morgan, the editor of the News of the World, and now the host of CNN’s Piers Morgan Tonight. In his 2005 book The Insider, he would recount with gusto the thoroughness with which Wade arranged to bug a hotel room in advance of a 1994 meeting between the paper’s editors and Princess Diana’s lover, James Hewitt. Taken with Wade, Morgan promoted her rapidly—too rapidly, some say. By 1995, when he left to become editor of the Daily Mirror, the 27-year-old Wade was the deputy editor of the News of the World.

Paul McMullan first met Wade in 1994, when she was still features editor. McMullan recalls how inexperienced she was. “She’d never done an investigation or written a news story,” he says, and she had little understanding of what went into the reporting of one. A former deputy to Wade, he is today a central figure in the hacking scandal, one of the few journalists to not only publicly admit that hacking was widely practiced but also to defend it. “I think you can do anything to get at the truth,” McMullan says. “The criticism is we did it so badly and so often under her stewardship it became ridiculous.” In the 90s, though, outright phone hacking was not that prevalent. Before digital-cell-phone technology became common, listening in on cell-phone conversations was done with scanners. It was, McMullan has said, why it was so easy for reporters to listen in on Princess Diana’s phone calls, for example. Just as widespread among newspapers, he says, was the use of private investigators to get unpublished phone numbers and addresses—and sometimes for such other “dark arts” as getting medical and financial records, and for surveillance.

McMullan says that Wade knew about the use of private investigators—“Impossible not to,” he says. “I was deputy features editor. I ran the same department that she did, and every week we’d see the bills from the private investigators: £2,000, £4,000.” However, he can’t be sure she always knew what they were doing.

“She was quite sweet in those days,” says McMullan. “She knew she was out of her depth and would rely on other people to make her shine. And, funnily enough, it was because she was so hopeless, we wanted to protect her as our boss when we would find out she didn’t know what she was doing,” he recalls. “So that worked, as one management style, if you like.”

“She’d get you to do things,” says another former News of the World reporter. “She had this charisma, this magnetic attraction,” he says. “She would praise to high heaven, make you feel like you were on top of the world. It was only afterwards that you realized you were manipulated.” In a largely male tabloid world—a business in which Brooks was once asked at a corporate golf gathering to sew a senior executive’s button back on his shirt, which she did—perceptions counted for a lot.

“She was very tactile, touching you on the arm, looking straight into your eyes as though there was no one more important in the room,” this former News reporter says. “From the way she acted, you would think she wanted to sleep with you.” But “no,” he says, “she didn’t want to sleep with the help; she was way too up the scale for that.”

She worked nonstop. “She was going at 150 all day,” this man recalls. “She was very intense. I thought she was a very insecure woman, actually, desperate for a lot of love and attention,” he says. “I was quite friendly with her at some point, as friendly as anyone can get with her, and in her quieter moments she would say, ‘No one loves me; I’m in a battle here.’ ” But even then, she was careful. Even out drinking after work, “she did not get pissed, ever. She never let her guard down,” and never spoke about her past. Like others, he wondered. “In the early days she used this accent, a girls’-school accent, meaning she’d been poshly educated, but every now and again the accent would slip and you’d realize: Oh, yeah.” There were rumors of a father who “was absent or who left,” of some kind of abandonment or “betrayal” that was felt deeply by her mother in particular, with whom Wade was, and still is, extremely close. But no one pressed.

Some believed her father was a vicar, or otherwise well-to-do, although, according to a copy of Brooks’s birth certificate, her father, John Robert Wade, was a tugboat deckhand. At some point, he became a gardener. In an interview with the BBC last summer, Brooks’s childhood friend Louise Weir would say that Brooks’s parents had a tree-pruning business that was so prosperous it afforded the family enviable vacations, and a personalized license plate for her mother, Deborah. When contacted, Weir was agitated, said she had been harassed by the media, and hung up the phone. But she told the BBC the Wades had been a churchgoing family. Rebekah, she said, was “a typical Gemini. She’s got her lovely fluffy side and her angry side She’s always been able to get what she wants out of people, even if they don’t really like her.”

In July 1996, a brief article appeared in the local Warrington Guardian. The occasion was Rebekah Wade’s engagement to Ross Kemp, whom she had met the year before at a golf tournament. The paper gushed about rumors that Wade’s engagement ring had cost $30,000. It also interviewed her father. John Wade was still living in Hatton, the small village where he and his then wife Deborah had been living when their daughter, Rebekah, was born. He said that he had no idea who Ross Kemp was, because he rarely watched television. However, he was “looking forward” to having Kemp visit him and his wife, Barbara, whom he’d married when Rebekah was 20. “The first time I knew of the engagement was when Rebekah rang to tell me she was getting married. It was quite a surprise,” he told the paper. Six weeks later, in September 1996, Wade died, at the age of 50. According to his death certificate, the cause was cirrhosis of the liver, so severe it had led to hepatic failure.

The Fantasy Daughter

When people who know Rupert Murdoch speak of his feelings for Rebekah Brooks, they use very emotional language: He “adores her,” “is devoted to her,” “is besotted with her.” The affection is clear in video clips and photographs of the two of them together—smiling into each other’s eyes, his arm around her, Brooks leaning in toward him. By most accounts, Rebekah Wade met Rupert Murdoch sometime in the mid-1990s, but it was not until the beginning of 1998 that people began to remark at how close they had become.

That January, Wade left the News of the World to become deputy editor of The Sun. It was a huge promotion—made by Murdoch despite the qualms of *The Sun’*s editor, Stuart Higgins. And almost from the moment she got that job, it was obvious to many that the job she wanted next was Higgins’s. Indeed, in May of that year Alastair Campbell, then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s press secretary, wrote in his diary—which was later published as Power & the People—of an “odd” party that Wade gave at the Belvedere, in Holland Park, “where you felt Stuart was being prepared for departure and her for his job.” But the following month the editorship of The Sunwent instead to David Yelland, the deputy editor of the New York Post. Although, as one former Blair adviser recalls, “she is too clever to have allowed herself to look insubordinate,” it was an open secret that she disliked Yelland, whose life, one News International executive recalls, “was made sort of miserable.” Two years later, in 2000, Murdoch once again promoted Wade. In a move that still baffles people, he suddenly fired Phil Hall, the respected editor of the News of the World, and gave his job to Wade. In 2003, when David Yelland resigned from The Sun, Murdoch installed Wade as the paper’s editor—the job, she would tell the staff on her first day, she had “dreamed of” ever since she was a child.

Although Murdoch has four daughters, two of them grown, over the years he has seemed closer to Brooks than to any of them. She was, people say, like the fantasy daughter, the daughter he always wished he had—the one who never argued with him, who devoted her life to pleasing him. They reportedly swim together in the mornings when he is in London. She fusses over him at dinner parties—making sure he’s eating, that his wineglass is full. “She’s very attentive,” says one News International executive.

“When she wants someone, she will woo them so intensely—there will be invitations, the sharing of confidences,” says a former friend. “She wraps herself around you.” Much as she apparently learned to play golf because one of her bosses did, she learned to sail because Murdoch enjoyed sailing, as does his family, including his older son, Lachlan, on whose yacht Rebekah reportedly spent the New Year’s holiday in 2002.

“It isn’t just Rupert who is in love with her; it’s also James and the family,” says one former News Corp. executive who has known the Murdochs for decades. While her relationship with Murdoch’s younger son, James, became closer in late 2007, when he was put in charge of News International, Wade had been friends with Elisabeth for more than a decade. In 2001, she was not only a guest at Elisabeth’s wedding to Matthew Freud, but among a select group invited to her bridal shower. The two spent weekends together in Chipping Norton. “They were all over each other in the country,” says a friend. In many ways, Brooks had become a member of the Murdoch family, which, says one Murdoch executive, “has been key in her rise.”

If to some in the Murdoch empire she was “the impostor daughter,” Brooks did share, more than any of his actual children, one of Murdoch’s great passions. “She was the one who expressed his love for newspapers,” says one newspaper executive. While many at News Corp. would be happy to sell the newspapers, says one former executive, and Murdoch’s children have not appeared to share his enthusiasm for the business, Brooks was as passionate about newspapers as Murdoch. He saw her as a “great campaigning editor.” Indeed, he supported one of her most controversial campaigns, the 2000 “Name & Shame” series for the News of the World, which was prompted by the murder of eight-year-old Sarah Payne by a registered sex offender. For two weeks, she published photographs, names, and the whereabouts of convicted pedophiles. In the process, she became very close to the child’s mother, Sara Payne, at one point giving her a company cell phone, which, according to investigators, may have been hacked, an allegation that Brooks said was “abhorrent.”

Murdoch loved Rebekah Wade’s “fantastic drive,” says one executive. More than anything, he loved the fact that her whole life was wrapped up in his beloved papers; when she was scooped by a rival, she could go into dark funks, so much so that on one occasion, when she was beaten to a story by the Mirror, Murdoch reportedly called Les Hinton, who at the time was the executive in charge of the U.K. newspaper business, to ask, “Is she all right?”

And at every turn, she gave him the papers he wanted. A co-founder of Women in Journalism, an organization to help promote women’s careers in the field, Wade—along with Murdoch’s former wife Anna—was reported to be personally offended by *The Sun’*s “Page 3,” which daily features photographs of bare-breasted women. But they were what Murdoch wanted, and so she continued to run the photos, and defended them roundly. In 2004, in response to criticisms of “Page 3” from Clare Short, a former Cabinet minister, Wade ran a “Hands Off Page 3” campaign which included running a photograph of Short’s head on a flabby, naked female body, and describing Short as “fat,” “ugly,” “short on looks,” and “short on brains.”

The Power and the Story

That July, six months after her savaging of Clare Short, Wade threw a 40th-birthday party for Ross Kemp. Cherie Blair came, as did Gordon Brown, then chancellor of the Exchequer, along with David Blunkett, the home secretary, and Lord Stevens, then chief of Scotland Yard. The star of Britain’s most popular television soap, Kemp was a big celebrity, and her relationship with him had helped catapult Wade into the limelight. But they had not come because of Kemp; the power now was hers—courtesy of Rupert Murdoch. At the News of the World and The Sun she ran not only two of Britain’s biggest newspapers but also ones that could, and did, destroy people’s lives and careers, frequently with a political agenda devoted to advancing Murdoch’s interests in Britain—particularly his profitable satellite-television business. The threat was always implicit: Stand in Murdoch’s way and the papers will retaliate. “Everybody was afraid,” says one prominent newspaper editor. To many it was “just a fact of life,” says this editor, “that you had to give in to them.” It was a fear that would reach into the highest levels of British politics, and among his many editors, none would be perceived as a more enthusiastic political partner to Murdoch than Wade.

She was not known to have strong political opinions. “Rebekah wore her politics lightly,” says one man, who adds that in the 15 years he has known her “I never heard her offer an opinion about anything in politics. She was interested in power.” And, it seemed, enjoyed wielding it.

She had gotten her first political toehold through Tony Blair—the prime minister now regarded as perhaps the most obsequious in his relationship to Murdoch. Wade met Blair through Kemp, who was a major Labour Party supporter and fund-raiser, but it was Alastair Campbell, an old friend of hers from his days as a tabloid journalist, who would really open doors to Downing Street for her. “The relationship between Alastair and Rebekah was a singularly close one,” recalls Lance Price, a former Blair spokesperson. Although she was just the deputy editor of the News of the World in 1997 when Blair was elected, largely because of Campbell, she had special access.

Wade became close to Blair and to his wife, Cherie—a “friendship” that would cool but continue even after the police discovered in 2002 that News reporters were planning to set Cherie up by taping a conversation between her and the boyfriend of her “life coach.” He had helped find the Blairs’ eldest son an apartment at a reduced price—an apparent favor to the prime minister, it eventually became a major story. The News would lambaste Cherie as “foolish” and “arrogant,” but Wade’s dinners and meetings with Tony Blair continued, perhaps encouraged by an editorial that appeared during her first week as editor of The Sun, a month after the swipe at his wife: “New Labour have had a good run for their money—your money, actually. But it’s time to say we’re very disappointed.” The Sun did not withdraw its backing for Blair; it was just a little reminder of who buttered his bread.

In a remarkable feat of social and emotional gymnastics, Wade would also become friendly with Gordon Brown. As chancellor of the Exchequer before he became prime minister, in 2007, Brown had a famously touchy relationship with Blair—which, according to Lord John Prescott, Wade deftly mined.

Deputy prime minister at the time, Prescott now recalls how “Rebekah Wade used to have dinner with Blair and Brown and play them off against each other.” He is still shocked at how easy it was. “If Blair wanted to know what Brown was doing, she’d fix the dinner up and then tell him,” he recalls. “They used to use her for intelligence on the other.” It was artful, he says, the way she made each man think that she was on his side. “I used to say, ‘Why are you listening to that bloody woman?’ It was all about Murdoch,” says Prescott, who is among the politicians who were hacked by the News—in his case, in 2006, following the exposure of an extramarital affair with his secretary.

As she did with Cherie Blair, Wade also became very close to Sarah Brown. It was something people would note—the intimacy of her friendships with the powerful as she befriended their husbands, wives, and children. That was “the nature of how she operates,” says Roy Greenslade. “She gets that close to people. It’s not simply a business thing—it’s a personal thing. It’s domestic.” But Wade’s friendship with the Browns did not stop her, in the fall of 2006, from phoning them with upsetting news. The Sun had discovered from an informant that the Browns’ infant son had cystic fibrosis, and the paper was going to run the story the next day. Which it did, on the cover, with the screaming headline chancellor’s baby has cystic fibrosis. The Browns, who had already lost a baby daughter and were still coming to terms with the news of their son’s illness, were devastated. It is this story—along with the revelation that Gordon Brown’s phone may have been hacked by the News of the World and his financial records accessed by Murdoch’s Sunday Times—that today particularly horrifies people. “If that doesn’t make your skin crawl, the evilness of it, what does?” says a Murdoch observer. It was a measure of Murdoch’s political power, and Rebekah Wade’s, that Gordon Brown was among the guests at her wedding three years later.

Not that this bit of fealty made any difference. That September, on the day Brown was to make a major speech, The Sun’s headline would read: labour’s lost it. *The Sun’*s sudden switch of allegiance from the Labour Party to David Cameron’s Conservatives shocked the British political establishment. To some, it was a typically cynical Murdochian move of backing the likely winner, but by then Brooks had also grown very close to Cameron, according to a friend of both Brooks’s and Cameron’s. Her deputy—then successor—at the News, and her close friend, Andy Coulson, had gone to work as Cameron’s media adviser after resigning from the News in 2007 following the hacking convictions of the paper’s royals editor, Clive Goodman, and the private investigator Glenn Mulcaire. The Conservative leader was also Brooks’s neighbor in Oxfordshire, and Charlie Brooks had gone to Eton with Cameron’s brother. Cameron dined at the Brooks’s home on weekends. And he was a guest at the annual New Year’s Eve bash, thrown by the Brookses with several other couples from the Oxfordshire set.

Within a week of Cameron’s election, in May 2010, Rupert Murdoch paid a visit to 10 Downing Street for a private meeting with the new prime minister. In July he visited again, shortly after his company made its bid to control BSkyB. What they discussed is anybody’s guess, but that same month Cameron’s administration criticized the BBC—the chief competitor to Murdoch’s BSkyB and a longtime Murdoch bête noire—for “extraordinary and outrageous” waste and proposed reducing its budget.

Absence and Malice