Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Page 1 of 3 • Share

Page 1 of 3 • 1, 2, 3

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Crimewatch: dupers or duped?

The October edition of Crimewatch, focussing on the case of Madeleine McCann, featured new photofits of a potential suspect - only, they weren't new. According to the Sunday Times, they had been repressed by the McCanns themselves. The failure of the BBC to report this is extraordinary.

David Elstein

4 November 2013

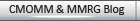

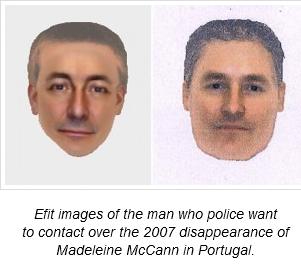

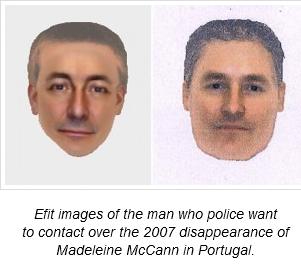

The newly released photofit in the Maddy McCann case

For nearly thirty years, Crimewatch has been a regular part of the schedule of the BBC’s main channel, BBC1. By using video reconstructions of unsolved crimes, and accepting help and advice from the UK’s police forces, it has contributed to the conviction of over one hundred major criminals, including murderers and rapists.

These days, Crimewatch no longer has a monthly slot, but it can still pull in a large audience. The October 14th edition, including a 25-minute report on the mysterious disappearance of 3-year-old Madeleine McCann during a family holiday in Portugal six years ago, attracted over 6.5 million viewers, along with a mass of publicity before and after transmission.

The occasion of the programme was the decision by Scotland Yard to present the main findings of its renewed efforts – involving a 37-strong investigative team – to find the child, prompted by an assurance given by Prime Minister David Cameron to Madeleine’s parents, Gerry and Kate, that the closing of the Portuguese investigation into the case would not be allowed to be the final word.

The programme item was curiously inept. Real footage of the McCann family was constantly intercut with shots of (not very) lookalikes: confusing and distracting at the same time. Towards the end, there was reference to a search for a number of long-haired men who had been seen hanging around the apartment block in the holiday resort: yet the only video the “reconstruction” managed to offer was of several men with close-cropped heads.

Much of the publicity the programme attracted centred on new electronic photofits that featured prominently in the programme. They had been generated in the course of interviews with an Irish family, the Smiths, who had also been on holiday in the Praia da Luz resort where the McCanns and some friends of theirs had gathered in April 2007.

Attentive viewers might have been puzzled as to how the Irish witnesses were able to provide such detailed images, six years after the event. We were not told. The interview with the detective leading the Scotland Yard inquiry did not touch on the subject.

The next day, October 15th, the Daily Express – part of the newspaper group owned by Richard Desmond which has paid out over half a million pounds to the McCanns in compensation for libellous stories about Madeleine’s disappearance – noted that these photofits were actually five years old, but had never been released publicly.

On October 27th, we learned more. The Sunday Times claimed that the photofits had actually been compiled in 2008 by a team of private investigators hired by the Find Madeleine Fund, which had been set up by the McCanns. The investigation had cost £500,000, and had been led by Henri Exton, a former head of MI5 undercover operations. But the company Exton had worked for, Oakley International, had fallen out with the McCanns.

Ostensibly, the dispute was over money, but the McCanns also imposed a ban on any publicising of the contents of the Exton report. According to the Sunday Times, it had contained criticisms of the evidence provided by the friends of the McCanns, and by the McCanns themselves, even raising the possibility that Madeleine might have died after wandering out of the family’s rented apartment through unsecured doors.

Over the years, the McCanns have issued seven different photofits, including one provided by their friend Jane Tanner, who thought she saw a man carrying a child at about 9.15 on the evening Madeleine disappeared. Exton discounted this sighting, and thought the Smith sighting, at about 10 pm, was the most significant. Yet the McCanns, despite passionately pursuing the quest to find their lost child, chose never to issue the Smith photofit.

The Scotland Yard team has now satisfied itself that the Tanner sighting can be excluded, agrees that the 10 pm timeline is the correct one and regards the Smith photofit as the most promising lead: five years after the McCanns themselves suppressed all this information, according to the Sunday Times.

Whatever their reasons for doing so, the McCanns are not accountable to the public, despite Gerry’s regular lectures on how the press in general should behave, and why a Royal Charter version of the Leveson recommendations is needed to keep newspapers honest and straightforward in their reporting.

The story in the Sunday Times also indicated that the Exton report included a section in which the father of the Smith family, Martin Smith, noted that his observation of how Gerry McCann used to carry Madeleine on his shoulder reminded him of the man he saw carrying a child at 10 pm on the night Madeleine disappeared. He does not think the man actually was Gerry, but it is not hard to work out why the leader of the Portuguese inquiry concluded that the McCanns were implicated in the disappearance. The McCanns are suing him for libel, and both the Portuguese police and Scotland Yard are satisfied they had no part in the disappearance, but fear of inciting more press speculation in the UK may explain the decision to suppress the entire Oakley report.

It is hard to believe that the Crimewatch team was ignorant of this history. It would have been incredibly unprofessional of them not even to ask how and when Scotland Yard had obtained the “new” photofits. The programme referred to the Irish family, and a “fresh” investigation, but the absence of any reference to “new” photofits strongly suggests that Crimewatch knew the background perfectly well.

Does this matter? Crimewatch occupies an uneasy space between entertainment and information. Its brief is undoubtedly one of public service, but it is not in the business of journalism. No journalist would go out of his way to mislead the public in the way this edition of Crimewatch managed to do.

The essence of Crimewatch is complicity: close co-operation with the police and the purported victims of crime, to the point of eliminating anything awkward that might get in the way of that joint endeavour. The Sunday Times quoted a source close to the McCanns as saying that release of the original Oakley investigation might have distracted the public from their objective of finding their child. Yet the bottom line of this story is that the parents deliberately withheld, for five years, the photofits that Scotland Yard now says are the most important evidence in the search for the supposed culprits. For any journalist, that would have been at least as important a fact to reveal to the public as the photofits themselves.

Yet the most important area of journalism in the UK – the BBC, which accounts for over 60% of all news consumption – has remained silent on the revelations in the Sunday Times. Even the BBC website, with over 900 stories related to the disappearance over the years, has not found room for that startling information (though you can find links to the Daily Star’s website, which repeated much of the Sunday Times material on October 28th). It would be dismaying if some kind of misguided loyalty to the non-journalists at Crimewatch was inhibiting the 8,000 BBC staff who work in its news division.

It is, of course, just possible that Crimewatch was itself duped by the McCanns: but I doubt it. Instead, the editor chose to join the McCanns in trying to dupe the public. Neither option shows the BBC in a good light. Whatever the failings over the two Newsnight items – the untransmitted one on Jimmy Savile, the transmitted one that libelled Lord McAlpine – no-one can argue that there was any definite intention to mislead the public. Sadly, the same cannot be said of October’s Crimewatch.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/ourbeeb/crimewatch-dupers-or-duped/

The October edition of Crimewatch, focussing on the case of Madeleine McCann, featured new photofits of a potential suspect - only, they weren't new. According to the Sunday Times, they had been repressed by the McCanns themselves. The failure of the BBC to report this is extraordinary.

David Elstein

4 November 2013

The newly released photofit in the Maddy McCann case

For nearly thirty years, Crimewatch has been a regular part of the schedule of the BBC’s main channel, BBC1. By using video reconstructions of unsolved crimes, and accepting help and advice from the UK’s police forces, it has contributed to the conviction of over one hundred major criminals, including murderers and rapists.

These days, Crimewatch no longer has a monthly slot, but it can still pull in a large audience. The October 14th edition, including a 25-minute report on the mysterious disappearance of 3-year-old Madeleine McCann during a family holiday in Portugal six years ago, attracted over 6.5 million viewers, along with a mass of publicity before and after transmission.

The occasion of the programme was the decision by Scotland Yard to present the main findings of its renewed efforts – involving a 37-strong investigative team – to find the child, prompted by an assurance given by Prime Minister David Cameron to Madeleine’s parents, Gerry and Kate, that the closing of the Portuguese investigation into the case would not be allowed to be the final word.

The programme item was curiously inept. Real footage of the McCann family was constantly intercut with shots of (not very) lookalikes: confusing and distracting at the same time. Towards the end, there was reference to a search for a number of long-haired men who had been seen hanging around the apartment block in the holiday resort: yet the only video the “reconstruction” managed to offer was of several men with close-cropped heads.

Much of the publicity the programme attracted centred on new electronic photofits that featured prominently in the programme. They had been generated in the course of interviews with an Irish family, the Smiths, who had also been on holiday in the Praia da Luz resort where the McCanns and some friends of theirs had gathered in April 2007.

Attentive viewers might have been puzzled as to how the Irish witnesses were able to provide such detailed images, six years after the event. We were not told. The interview with the detective leading the Scotland Yard inquiry did not touch on the subject.

The next day, October 15th, the Daily Express – part of the newspaper group owned by Richard Desmond which has paid out over half a million pounds to the McCanns in compensation for libellous stories about Madeleine’s disappearance – noted that these photofits were actually five years old, but had never been released publicly.

On October 27th, we learned more. The Sunday Times claimed that the photofits had actually been compiled in 2008 by a team of private investigators hired by the Find Madeleine Fund, which had been set up by the McCanns. The investigation had cost £500,000, and had been led by Henri Exton, a former head of MI5 undercover operations. But the company Exton had worked for, Oakley International, had fallen out with the McCanns.

Ostensibly, the dispute was over money, but the McCanns also imposed a ban on any publicising of the contents of the Exton report. According to the Sunday Times, it had contained criticisms of the evidence provided by the friends of the McCanns, and by the McCanns themselves, even raising the possibility that Madeleine might have died after wandering out of the family’s rented apartment through unsecured doors.

Over the years, the McCanns have issued seven different photofits, including one provided by their friend Jane Tanner, who thought she saw a man carrying a child at about 9.15 on the evening Madeleine disappeared. Exton discounted this sighting, and thought the Smith sighting, at about 10 pm, was the most significant. Yet the McCanns, despite passionately pursuing the quest to find their lost child, chose never to issue the Smith photofit.

The Scotland Yard team has now satisfied itself that the Tanner sighting can be excluded, agrees that the 10 pm timeline is the correct one and regards the Smith photofit as the most promising lead: five years after the McCanns themselves suppressed all this information, according to the Sunday Times.

Whatever their reasons for doing so, the McCanns are not accountable to the public, despite Gerry’s regular lectures on how the press in general should behave, and why a Royal Charter version of the Leveson recommendations is needed to keep newspapers honest and straightforward in their reporting.

The story in the Sunday Times also indicated that the Exton report included a section in which the father of the Smith family, Martin Smith, noted that his observation of how Gerry McCann used to carry Madeleine on his shoulder reminded him of the man he saw carrying a child at 10 pm on the night Madeleine disappeared. He does not think the man actually was Gerry, but it is not hard to work out why the leader of the Portuguese inquiry concluded that the McCanns were implicated in the disappearance. The McCanns are suing him for libel, and both the Portuguese police and Scotland Yard are satisfied they had no part in the disappearance, but fear of inciting more press speculation in the UK may explain the decision to suppress the entire Oakley report.

It is hard to believe that the Crimewatch team was ignorant of this history. It would have been incredibly unprofessional of them not even to ask how and when Scotland Yard had obtained the “new” photofits. The programme referred to the Irish family, and a “fresh” investigation, but the absence of any reference to “new” photofits strongly suggests that Crimewatch knew the background perfectly well.

Does this matter? Crimewatch occupies an uneasy space between entertainment and information. Its brief is undoubtedly one of public service, but it is not in the business of journalism. No journalist would go out of his way to mislead the public in the way this edition of Crimewatch managed to do.

The essence of Crimewatch is complicity: close co-operation with the police and the purported victims of crime, to the point of eliminating anything awkward that might get in the way of that joint endeavour. The Sunday Times quoted a source close to the McCanns as saying that release of the original Oakley investigation might have distracted the public from their objective of finding their child. Yet the bottom line of this story is that the parents deliberately withheld, for five years, the photofits that Scotland Yard now says are the most important evidence in the search for the supposed culprits. For any journalist, that would have been at least as important a fact to reveal to the public as the photofits themselves.

Yet the most important area of journalism in the UK – the BBC, which accounts for over 60% of all news consumption – has remained silent on the revelations in the Sunday Times. Even the BBC website, with over 900 stories related to the disappearance over the years, has not found room for that startling information (though you can find links to the Daily Star’s website, which repeated much of the Sunday Times material on October 28th). It would be dismaying if some kind of misguided loyalty to the non-journalists at Crimewatch was inhibiting the 8,000 BBC staff who work in its news division.

It is, of course, just possible that Crimewatch was itself duped by the McCanns: but I doubt it. Instead, the editor chose to join the McCanns in trying to dupe the public. Neither option shows the BBC in a good light. Whatever the failings over the two Newsnight items – the untransmitted one on Jimmy Savile, the transmitted one that libelled Lord McAlpine – no-one can argue that there was any definite intention to mislead the public. Sadly, the same cannot be said of October’s Crimewatch.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/ourbeeb/crimewatch-dupers-or-duped/

Guest- Guest

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Madeleine McCann: The Earliest Account of the Abduction

By Jason Michael - 2nd December 2016

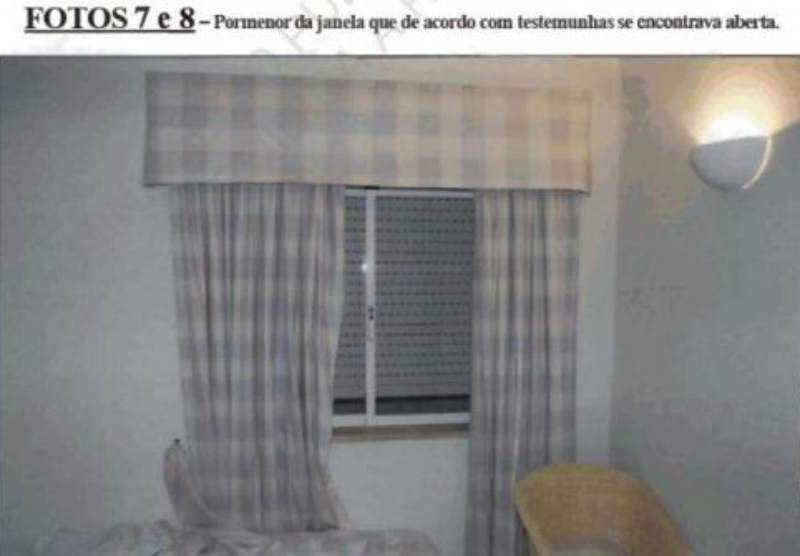

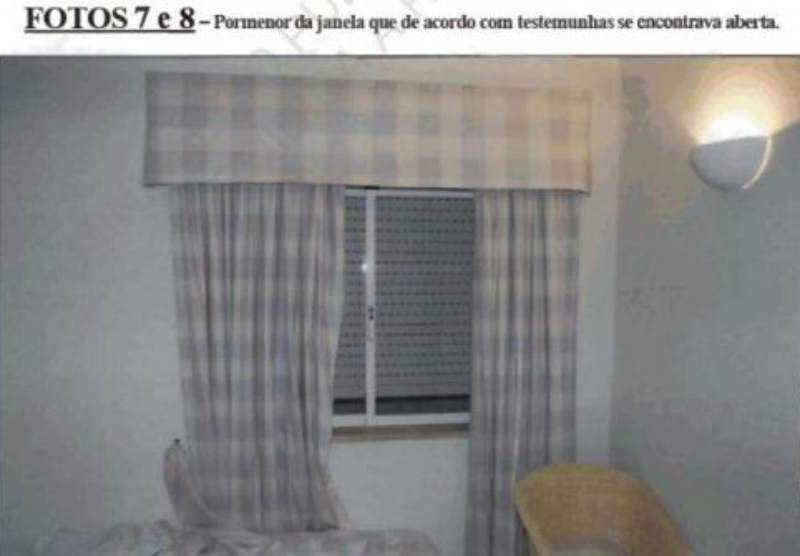

In the earliest reports of the abduction of “Maddie” McCann her parents said that the shutters and window to her room had been forced open. After forensic investigation this was found not to have been the case. How can this discrepancy be explained?

At the Ocean Summer Club resort on the Portuguese Algarve on the chilly windless evening of Thursday 3 May 2007 a three year old girl was reported missing from apartment 5A by her parents Gerry and Kate McCann. Madeleine had been left sleeping in her bedroom, along with her siblings – twins – Amelie and Sean, from about half past eight in the evening until ten while Gerry and Kate enjoyed an evening meal with friends a short distance away at the resort’s Tapas Restaurant. Close to ten o’clock that night Kate returned to the apartment alone to check on her children. On discovering that “Maddie” was not in her bed, Kate claims to have searched the two-bedroom apartment before alerting her husband and friends at the restaurant that her daughter was missing.

We know, from the account of the resort manager John Hill, that the police were called from the reception and that many residents came together to conduct a search around the resort for the missing child. At this point in the story everything seems quite normal. We have a distraught mother looking for her young daughter, a call to the police, and other concerned holiday makers offering their help to look for the missing girl. But rather quickly the story begins to get confused. Kate and Gerry’s versions of events change in significant detail over the first twenty-four hours, ultimately raising the suspicions of the Portuguese authorities. The entire case now amounts to a huge corpus of evidence; books, and newspaper articles, but for the moment we will focus on the initial report.

On the night before giving her first formal statement to the police – the Polícia Judiciária – the following morning (Friday 5 May 2007) Kate, quite naturally, made a telephone call to her father, Brian Healy, back in England. According to a report in the Guardian newspaper (5 May 2007) Gerry McCann explained to his father-in-law during this conversation what had happened. “The shutters to the room had been broken,” Mr. Healy recalls Gerry telling him, “they were jemmied up and [Madeleine] was gone.”

A person or persons unknown had used some implement to crowbar open the external aluminium blackout blinds and forced open the window to the children’s room at apartment 5A before climbing in to snatch the sleeping toddler from her bed. This is a significant piece of information, and one which was repeated to at least three other people that same night; Gerry McCann’s sister Trisha Cameron, Madeleine’s godfather Jon Corner, and Kate McCann’s friend Gill Renwick. Each of these people stated this version of events to the British media the following morning.

During an interview with the BBC Trish Cameron said that “the front door was lying open, the windows had been tampered with, the shutters had been jemmied open… and Madeleine was missing.” Gill Renwick, on a phone in to GMTV, gave the same details, as did Jon Corner in his interviews with the Independent and the Mirror newspapers. It is safe to say that this was the version of events first reported by the McCanns on the night that their daughter was taken. With one seemingly minor difference this was the same account Gerry gave to the Polícia Judiciária in his 11.15 statement the next morning.

In this interview Gerry, who was interviewed alone, told the Portuguese police that his wife – Kate McCann – had opened the front door with a key; contradicting the report that the front door was lying open. He went on to state that she found that “the door to the children’s bedroom was completely open, the window was also open, the blinds were raised and the curtains were drawn open.” There was no mention in this interview that the front door was wide open, and what might appear here to be a simple confusion becomes, over the next few days, to be the first alteration in the significant details of the discovery that Madeleine was missing. All that remains consistent in Gerry and Kate’s testimony from that night to this is the singular fact that their daughter was missing.

Gerry, in a strange concession, was allowed to remain in the interview room while his wife was being interviewed. She remarks in her book that he placed his hand on her shoulder from time to time and gave her hand the odd reassuring squeeze. Considering that both would later be made “Arguidos” or suspects in the case, this is a truly extraordinary allowance on the part of the investigators. In this interview Kate was adamant that the windows and curtains in the room were closed and that the shutters were fully down and locked.

It was John Hill, the manager of the Ocean Summer Club, who first commented that “there was no sign” of a forced entry. From what he could see there was no damage to the exterior shutters and that the windows had not been forced open. According to him there was no damage whatsoever. The police and the forensic experts came to the same conclusion. Chief Inspector Olegario Sousa determined that the window locking mechanism made it almost impossible for them to be opened from the outside without causing considerable damage, and that there was no damage to the window or the lock. After inspecting the shutters he agreed with the manager’s assessment that no one had tampered with them. Even the British forensic investigator, Professor David Barclay, concluded that this was impossible and that no forensic evidence was found on them or the windows.

In their second interviews with the Polícia Judiciária the details presented by Gerry and Kate would be completely different from those given during their first interviews and the accounts they had first relayed back to family and friends in the UK. Without more evidence it is not easy to explain these discrepancies, but that they exist is reason enough to look more closely at the events of the night of the disappearance. We must be critical of the accounts of the McCanns and pay more attention to the statements given by their friends at the time.

One Year Later, McCanns Renew Appeal

https://randompublicjournal.com/2016/12/02/madeleine-mccann-the-earliest-account-of-the-abduction/

By Jason Michael - 2nd December 2016

In the earliest reports of the abduction of “Maddie” McCann her parents said that the shutters and window to her room had been forced open. After forensic investigation this was found not to have been the case. How can this discrepancy be explained?

At the Ocean Summer Club resort on the Portuguese Algarve on the chilly windless evening of Thursday 3 May 2007 a three year old girl was reported missing from apartment 5A by her parents Gerry and Kate McCann. Madeleine had been left sleeping in her bedroom, along with her siblings – twins – Amelie and Sean, from about half past eight in the evening until ten while Gerry and Kate enjoyed an evening meal with friends a short distance away at the resort’s Tapas Restaurant. Close to ten o’clock that night Kate returned to the apartment alone to check on her children. On discovering that “Maddie” was not in her bed, Kate claims to have searched the two-bedroom apartment before alerting her husband and friends at the restaurant that her daughter was missing.

We know, from the account of the resort manager John Hill, that the police were called from the reception and that many residents came together to conduct a search around the resort for the missing child. At this point in the story everything seems quite normal. We have a distraught mother looking for her young daughter, a call to the police, and other concerned holiday makers offering their help to look for the missing girl. But rather quickly the story begins to get confused. Kate and Gerry’s versions of events change in significant detail over the first twenty-four hours, ultimately raising the suspicions of the Portuguese authorities. The entire case now amounts to a huge corpus of evidence; books, and newspaper articles, but for the moment we will focus on the initial report.

On the night before giving her first formal statement to the police – the Polícia Judiciária – the following morning (Friday 5 May 2007) Kate, quite naturally, made a telephone call to her father, Brian Healy, back in England. According to a report in the Guardian newspaper (5 May 2007) Gerry McCann explained to his father-in-law during this conversation what had happened. “The shutters to the room had been broken,” Mr. Healy recalls Gerry telling him, “they were jemmied up and [Madeleine] was gone.”

A person or persons unknown had used some implement to crowbar open the external aluminium blackout blinds and forced open the window to the children’s room at apartment 5A before climbing in to snatch the sleeping toddler from her bed. This is a significant piece of information, and one which was repeated to at least three other people that same night; Gerry McCann’s sister Trisha Cameron, Madeleine’s godfather Jon Corner, and Kate McCann’s friend Gill Renwick. Each of these people stated this version of events to the British media the following morning.

During an interview with the BBC Trish Cameron said that “the front door was lying open, the windows had been tampered with, the shutters had been jemmied open… and Madeleine was missing.” Gill Renwick, on a phone in to GMTV, gave the same details, as did Jon Corner in his interviews with the Independent and the Mirror newspapers. It is safe to say that this was the version of events first reported by the McCanns on the night that their daughter was taken. With one seemingly minor difference this was the same account Gerry gave to the Polícia Judiciária in his 11.15 statement the next morning.

In this interview Gerry, who was interviewed alone, told the Portuguese police that his wife – Kate McCann – had opened the front door with a key; contradicting the report that the front door was lying open. He went on to state that she found that “the door to the children’s bedroom was completely open, the window was also open, the blinds were raised and the curtains were drawn open.” There was no mention in this interview that the front door was wide open, and what might appear here to be a simple confusion becomes, over the next few days, to be the first alteration in the significant details of the discovery that Madeleine was missing. All that remains consistent in Gerry and Kate’s testimony from that night to this is the singular fact that their daughter was missing.

Gerry, in a strange concession, was allowed to remain in the interview room while his wife was being interviewed. She remarks in her book that he placed his hand on her shoulder from time to time and gave her hand the odd reassuring squeeze. Considering that both would later be made “Arguidos” or suspects in the case, this is a truly extraordinary allowance on the part of the investigators. In this interview Kate was adamant that the windows and curtains in the room were closed and that the shutters were fully down and locked.

It was John Hill, the manager of the Ocean Summer Club, who first commented that “there was no sign” of a forced entry. From what he could see there was no damage to the exterior shutters and that the windows had not been forced open. According to him there was no damage whatsoever. The police and the forensic experts came to the same conclusion. Chief Inspector Olegario Sousa determined that the window locking mechanism made it almost impossible for them to be opened from the outside without causing considerable damage, and that there was no damage to the window or the lock. After inspecting the shutters he agreed with the manager’s assessment that no one had tampered with them. Even the British forensic investigator, Professor David Barclay, concluded that this was impossible and that no forensic evidence was found on them or the windows.

In their second interviews with the Polícia Judiciária the details presented by Gerry and Kate would be completely different from those given during their first interviews and the accounts they had first relayed back to family and friends in the UK. Without more evidence it is not easy to explain these discrepancies, but that they exist is reason enough to look more closely at the events of the night of the disappearance. We must be critical of the accounts of the McCanns and pay more attention to the statements given by their friends at the time.

One Year Later, McCanns Renew Appeal

https://randompublicjournal.com/2016/12/02/madeleine-mccann-the-earliest-account-of-the-abduction/

Guest- Guest

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Exactly the sort of thing a half decent Investigative Journalist would have discovered for him/her-self in the first 48 hours.

Laurenceldt likes this post

Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

The photofit on the left looks like Russell O'Brian to me.

crusader- Forum support

- Posts : 6808

Activity : 7159

Likes received : 345

Join date : 2019-03-12

Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Madeleine McCann's abductors should beware, the police will not give up

By Jim Gamble

Mon 14 Oct 2013 17.30 BST

This is not the time to criticise parenting or policing, it is time to pause and consider the developments in the case

A social worker once told me that when faced with a highly emotive child protection situation, the most important thing is having the presence of mind to pause. As Kipling put it, to "keep your head when all about you/ Are losing theirs." Pausing to plan a response in a crisis is critical.

When Madeleine McCann went missing in 2007, police in Portugal were faced with a difficult and highly charged scenario, no doubt made more complex by parental anxiety, along with language and cultural differences. As those first few hours disappeared in confusion and miscommunication, valuable minutes will have been lost. As hours turned to days there was little sense of pause, planning or direction, but no shortage of offers to help. There wasn't a policing agency in the UK that did not want to do all that it could to assist in the search for the little girl, whose picture was embedded in the public's conscience.

As the months rolled by with no sign of Madeleine, for a period of time her parents became aguidos, suspects, in the investigation. The only unusual thing about that was that it did not happen earlier; investigators always clear the ground beneath their feet and in doing this you look at the parents.

Many people have opinions about Kate and Gerry McCann. The rights and wrongs of their meal at the tapas bar and their approach to checking on the children. I am of the view that there but for the grace of God go I. For those perfect parents who have never left their children for a moment, think on this: if that was a lapse, they have paid a terrible price for it and they are still living the nightmare. No one but the person who took Madeleine is to blame for what has happened to her.

Others ask why all the attention for one child when so many go missing? They confuse children pushed or pulled from their homes in the UK by unhappy circumstances, sexual predators and so-called friends, with cases like Madeleine and Ben Needham. In the first instance the majority of those who go missing in the UK return home within 72 hours. They need greater attention, more resources and focus but their circumstances are different. Cases like Ben Needham and Madeleine, missing and suspected abducted abroad, are thankfully rare.

As the Metropolitan police investigation begins to gather pace, we have heard of new persons of interest, thousands of lines of inquiry, including highly valuable telecoms data and, critically, a much-improved working relationship with their Portuguese colleagues. All of that must be welcomed and while there will come a point to reflect on why some of this has taken so long, this is not that time.

Whether you were in Praia De Luz in May 2007 or not, you might hold the key, that piece of information which identifies a person or event, possibly even a phone number. Pause for a moment and consider the significant developments the police are sharing. Listen to the new timeline and look at the efit images. Someone out there knows, or has harboured suspicions, in either case now is the time to come forward.

The person or people responsible have an uncomfortable week ahead. They probably thought they had weathered the storm but it's time for them to start looking over their shoulder again. Thanks to her parents' persistent campaigning, the search for Madeleine goes on.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/14/madeleine-mccann-abductors-police

By Jim Gamble

Mon 14 Oct 2013 17.30 BST

This is not the time to criticise parenting or policing, it is time to pause and consider the developments in the case

A social worker once told me that when faced with a highly emotive child protection situation, the most important thing is having the presence of mind to pause. As Kipling put it, to "keep your head when all about you/ Are losing theirs." Pausing to plan a response in a crisis is critical.

When Madeleine McCann went missing in 2007, police in Portugal were faced with a difficult and highly charged scenario, no doubt made more complex by parental anxiety, along with language and cultural differences. As those first few hours disappeared in confusion and miscommunication, valuable minutes will have been lost. As hours turned to days there was little sense of pause, planning or direction, but no shortage of offers to help. There wasn't a policing agency in the UK that did not want to do all that it could to assist in the search for the little girl, whose picture was embedded in the public's conscience.

As the months rolled by with no sign of Madeleine, for a period of time her parents became aguidos, suspects, in the investigation. The only unusual thing about that was that it did not happen earlier; investigators always clear the ground beneath their feet and in doing this you look at the parents.

Many people have opinions about Kate and Gerry McCann. The rights and wrongs of their meal at the tapas bar and their approach to checking on the children. I am of the view that there but for the grace of God go I. For those perfect parents who have never left their children for a moment, think on this: if that was a lapse, they have paid a terrible price for it and they are still living the nightmare. No one but the person who took Madeleine is to blame for what has happened to her.

Others ask why all the attention for one child when so many go missing? They confuse children pushed or pulled from their homes in the UK by unhappy circumstances, sexual predators and so-called friends, with cases like Madeleine and Ben Needham. In the first instance the majority of those who go missing in the UK return home within 72 hours. They need greater attention, more resources and focus but their circumstances are different. Cases like Ben Needham and Madeleine, missing and suspected abducted abroad, are thankfully rare.

As the Metropolitan police investigation begins to gather pace, we have heard of new persons of interest, thousands of lines of inquiry, including highly valuable telecoms data and, critically, a much-improved working relationship with their Portuguese colleagues. All of that must be welcomed and while there will come a point to reflect on why some of this has taken so long, this is not that time.

Whether you were in Praia De Luz in May 2007 or not, you might hold the key, that piece of information which identifies a person or event, possibly even a phone number. Pause for a moment and consider the significant developments the police are sharing. Listen to the new timeline and look at the efit images. Someone out there knows, or has harboured suspicions, in either case now is the time to come forward.

The person or people responsible have an uncomfortable week ahead. They probably thought they had weathered the storm but it's time for them to start looking over their shoulder again. Thanks to her parents' persistent campaigning, the search for Madeleine goes on.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/14/madeleine-mccann-abductors-police

Guest- Guest

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

My months with Madeleine

By Bridget O'Donnell

Fri 14 Dec 2007 11.54 GMT

It was a welcome spring break, a chance to relax at a child-friendly resort in Portugal. Soon Bridget O'Donnell and her partner were making friends with another holidaying family while their three-year-old daughters played together. But then Madeleine McCann went missing and everyone was sucked into a nightmare

We lay by the members-only pool staring at the sky. Round and round, the helicopters clacked and roared. Their cameras pointed down at us, mocking the walled and gated enclave. Circles rippled out across the pool. It was the morning after Madeleine went.

Six days earlier we had landed at Faro airport. The coach was full of people like us, parents lugging multiple toddler/baby combinations. All of us had risen at dawn, rushed along motorways and hurtled across the sky in search of the modern solution to our exhaustion - the Mark Warner kiddie club. I travelled with my partner Jes, our three-year-old daughter, and our nine-month-old baby son. Praia da Luz was the nearest Mark Warner beach resort and this was the cheapest week of the year - a bargain bucket trip, for a brief lie-down.

Excitedly, we were shown to our apartments. Ours was on the fourth floor, overlooking a family and toddler pool, opposite a restaurant and bar called the Tapas. I worried about the height of the balcony. Should we ask for one on the ground floor? Was I a paranoid parent? Should I make a fuss, or just enjoy the view?

We could see the beach and a big blue sky. We went outside to explore.

We settled in over the following days. There was a warm camaraderie among the parents, a shared happy weariness and deadpan banter. Our children made friends in the kiddie club and at the drop-off, we would joke about the fact that there were 10 blonde three-year-old girls in the group. They were bound to boss around the two boys.

The children went sailing and swimming, played tennis and learned a dance routine for the end-of-week show. Each morning, our daughter ran ahead of us to get to the kiddie club. She was having a wonderful time. Jes signed up for tennis lessons. I read a book. He made friends. I read another book.

The Mark Warner nannies brought the children to the Tapas restaurant to have tea at the end of each day. It was a friendly gathering. The parents would stand and chat by the pool. We talked about the children, about what we did at home. We were hopeful about a change in the weather. We eyed our children as they played. We didn't see anyone watching.

Some of the parents were in a larger group. Most of them worked for the NHS and had met many years before in Leicestershire. Now they lived in different parts of the UK, and this holiday was their opportunity to catch up, to introduce their children, to reunite. They booked a large table every night in the Tapas. We called them "the Doctors". Sometimes we would sit out on our balcony and their laughter would float up around us. One man was the joker. He had a loud Glaswegian accent. He was Gerry McCann. He played tennis with Jes.

One morning, I saw Gerry and his wife Kate on their balcony, chatting to their friends on the path below. Privately I was glad we didn't get their apartment. It was on a corner by the road and people could see in. They were exposed.

In the evenings, babysitting at the resort was a dilemma. "Sit-in" babysitters were available but were expensive and in demand, and Mark Warner blurb advised us to book well in advance. The other option was the babysitting service at the kiddie club, which was a 10-minute walk from the apartment. The children would watch a cartoon together and then be put to bed. You would then wake them, carry them back and put them to bed again in the apartment. After taking our children to dinner a couple of times, we decided on the Wednesday night to try the service at the club.

We had booked a table for two at Tapas and were placed next to the Doctors' regular table. One by one, they started to arrive. The men came first. Gerry McCann started chatting across to Jes about tennis. Gerry was outgoing, a wisecracker, but considerate and kind, and he invited us to join them. We discussed the children. He told us they were leaving theirs sleeping in the apartments. While they chatted on, I ruminated on the pros and cons of this. I admired them, in a way, for not being paranoid parents, but I decided that our apartment was too far off even to contemplate it. Our baby was too young and I would worry about them waking up.

My phone rang as our food arrived; our baby had woken up. I walked the round trip to collect him from the kiddie club, then back to the restaurant. He kept crying and eventually we left our meal unfinished and walked back again to the club to fetch our sleeping daughter. Jes carried her home in a blanket. The next night we stayed in. It was Thursday, May 3.

Earlier that day there had been tennis lessons for the children, with some of the parents watching proudly as their girls ran across the court chasing tennis balls. They took photos. Madeleine must have been there, but I couldn't distinguish her from the others. They all looked the same - all blonde, all pink and pretty.

Jes and Gerry were playing on the next court. Afterwards, we sat by the pool and Gerry and Kate talked enthusiastically to the tennis coach about the following day's tournament. We watched them idly - they had a lot of time for people, they listened. Then Gerry stood up and began showing Kate his new tennis stroke. She looked at him and smiled. "You wouldn't be interested if I talked about my tennis like that," Jes said to me. We watched them some more. Kate was calm, still, quietly beautiful; Gerry was confident, proud, silly, strong. She watched his boyish demonstration with great seriousness and patience. That was the last time I saw them that day. Jes saw Gerry that night.

Our baby would not sleep and at about 8.30pm, Jes took him out for a walk in the buggy to settle him. Gerry was on his way back from checking on his children and the two men stopped to have a chat. They talked about daughters, fathers, families. Gerry was relaxed and friendly. They discussed the babysitting dilemmas at the resort and Gerry said that he and Kate would have stayed in too, if they had not been on holiday in a group. Jes returned to our apartment just before 9.30pm. We ate, drank wine, watched a DVD and then went to bed. On the ground floor, a completely catastrophic event was taking place. On the fourth floor of the next block, we were completely oblivious.

At 1am there was a frantic banging on our door. Jes got up to answer. I stayed listening in the dark. I knew it was bad; it could only be bad. I heard male mumbling, then Jes's voice. "You're joking?" he said. It wasn't the words, it was the tone that made me flinch. He came back in to the room. "Gerry's daughter's been abducted," he said. "She ..." I jumped up and went to check our children. They were there. We sat down. We got up again. Weirdly, I did the washing-up. We wondered what to do. Jes had asked if they needed help searching and was told there was nothing he could do; she had been missing for three hours. Jes felt he should go anyway, but I wanted him to stay with us. I was a coward, afraid to be alone with the children - and afraid to be alone with my thoughts.

I once worked as a producer in the BBC crime unit. I directed many reconstructions and spent my second pregnancy producing new investigations for Crimewatch. Detectives would call me daily, detailing their cases, and some stories stay with me still, such as the ones about a girl being snatched from her bath, or her bike, or her garden and then held in the passenger seat, or stuffed in the boot. There was always a vehicle, and the first few hours were crucial to the outcome. Afterwards, they would be dumped naked in an alley, or at a petrol station with a £10 note to "get a cab back to Mummy". They would be found within an hour or two. Sometimes.

From the balcony we could see some figures scratching at the immense darkness with tiny torch lights. Police cars arrived and we thought that they would take control. We lay on the bed but we could not sleep.

The next morning, we made our way to breakfast and met one of the Doctors, the one who had come round in the night. His young daughter looked up at us from her pushchair. There was no news. They had called Sky television - they didn't know what else to do. He turned away and I could see he was going to weep.

People were crying in the restaurant. Mark Warner had handed out letters informing them what had happened in the night, and we all wondered what to do. Mid-sentence, we would drift in to the middle distance. Tears would brim up and recede.

Our daughter asked us about the kiddie club that day. She had been looking forward to their dance show that afternoon. Jes and I looked at each other. My first instinct was that we should not be parted from our children. Of course we shouldn't; we should strap them to us and not let them out of our sight, ever again. But then we thought: how are we going to explain this to our daughter? Or how, if we spent the day in the village, would we avoid repeatedly discussing what had happened in front of her as we met people on the streets? What does a good parent do? Keep the children close or take a deep breath and let them go a little, pretend this was the same as any other day?

We walked towards the kiddie club. No one else was there. We felt awful, such terrible parents for even considering the idea. Then we saw, waiting inside, some of the Mark Warner nannies. They had been up most of the night but had still turned up to work that day. They were intelligent, thoughtful young women and we liked and trusted them. The dance show was cancelled, but they wanted to put on a normal day for the children. Our daughter ran inside and started painting. Then, behind us, another set of parents arrived looking equally washed out. Then another, and another. We decided, in the end, to leave them for two hours. We put their bags on the pegs and saw the one labelled "Madeleine". Heads bent, we walked away, into the guilty glare of the morning sun.

Locals and holidaymakers had started circulating photocopied pictures of Madeleine, while others continued searching the beaches and village apartments. People were talking about what had happened or sat silently, staring blankly. We didn't see any police.

Later, there was a knock on our apartment door and we let the two men in. One was a uniformed Portuguese policeman, the other his translator. The translator had a squint and sweated slightly. He was breathless, perhaps a little excited. We later found out he was Robert Murat. He reminded me of a boy in my class at school who was bullied.

Through Murat we answered a few questions and gave our details, which the policeman wrote down on the back of a bit of paper. No notebook. Then he pointed to the photocopied picture of Madeleine on the table. "Is this your daughter?" he asked. "Er, no," we said. "That's the girl you are meant to be searching for." My heart sank for the McCanns.

As the day drew on, the media and more police arrived and we watched from our balcony as reporters practised their pieces to camera outside the McCanns' apartment. We then went back inside and watched them on the news.

We had to duck under the police tape with the pushchair to buy a pint of milk. We would roll past sniffer dogs, local police, then national police, local journalists, and then international journalists, TV reporters and satellite vans. A hundred pairs of eyes and a dozen cameras silently swivelled as we turned down the bend. We pretended, for the children's sake, that this was nothing unusual. Later on, our daughter saw herself with Daddy on TV. That afternoon we sat by the members-only pool, watching the helicopters watching us. We didn't know what else to do.

Saturday came, our last day. While we waited for the airport coach to pick us up, we gathered round the toddler pool by Tapas, making small talk in front of the children. I watched my baby son and daughter closely, shamefully grateful that I could.

We had not seen the McCanns since Thursday, when suddenly they appeared by the pool. The surreal limbo of the past two days suddenly snapped back into painful, awful realtime. It was a shock: the physical transformation of these two human beings was sickening - I felt it as a physical blow. Kate's back and shoulders, her hands, her mouth had reshaped themselves in to the angular manifestation of a silent scream. I thought I might cry and turned so that she wouldn't see. Gerry was upright, his lips now drawn into a thin, impenetrable line. Some people, including Jes, tried to offer comfort. Some gave them hugs. Some stared at their feet, words eluding them. We all wondered what to do. That was the last time we saw Gerry and Kate.

The rest of us left Praia da Luz together, an isolated Mark Warner group. The coach, the airport, the plane passed quietly. There were no other passengers except us. We arrived at Gatwick in the small hours of an early May morning. No jokes, no banter, just goodbye. Though we did not know it then, those few days in May were going to dominate the rest of our year.

"Did you have a good trip?" asked the cabbie at Gatwick, instantly underlining the conversational dilemma that would occupy the first few weeks: Do we say "Yes, thanks" and move swiftly on? Or divulge the "yes-but-no-but" truth of our "Maddy" experience? Everybody talks about holidays, they make good conversational currency at work, at the hairdresser's, in the playground. Everybody asked about ours. I would pause and take a breath, deciding whether there was enough time for what was to follow. People were genuinely horrified by what had happened to Madeleine and even by what we had been through (though we thought ourselves fortunate). Their humanity was a balm and a comfort to us; we needed to talk about it, chew it over and share it out, to make it a little easier to swallow.

The British police came round shortly after our return. Jes was pleased to give them a statement. The Portuguese police had never asked.

As the summer months rolled by, we thought the story would slowly and sadly ebb away, but instead it flourished and multiplied, and it became almost impossible to talk about any-thing else. Friends came for dinner and we would actively try to steer the conversation on to a different subject, always to return to Madeleine. Others solicited our thoughts by text message after any major twist or turn in the case. Acquaintances discussed us in the context of Madeleine, calling in the middle of their debates to clarify details.

I found some immunity in a strange, guilty happiness. We had returned unscathed to our humdrum family routine, my life was wonderful, my world was safe, I was lucky, I was blessed. The colours in the park were acute and hyper-real and the sun warmed my face.

At the end of June, the first cloud appeared. A Portuguese journalist called Jes's mobile (he had left his number with the Portuguese police). The journalist, who was writing for a magazine called Sol, called Jes incessantly. We both work in television and cannot claim to be green about the media, but this was a new experience. Jes learned this the hard way. Torn between politeness and wanting to get the journalist off the line without actually saying anything, he had to put the phone down, but he had already said too much. Her article pitched the recollections of "Jeremy Wilkins, television producer" against those of the "Tapas Nine", the group of friends, including the McCanns, whom we had nicknamed the Doctors. The piece was published at the end of June. Throughout July, Sol's testimony meant Jes became incorporated into all the Madeleine chronologies. More clouds began to gather - this time above our house.

In August, the doorbell rang. The man was from the Daily Mail. He asked if Jes was in (he wasn't). After he left I spent an anxious evening analysing what I had said, weighing up the possible consequences. The Sol article had brought the Daily Mail; what would happen next? Two days later, the Mail came for Jes again. This time they had computer printout pictures of a bald, heavy-set man seen lurking in some Praia da Luz holiday snaps. The chatroom implication was that the man was Madeleine's abductor. There was talk on the web, the reporter insinuated, that this man might be Jes. I laughed at the ridiculousness of it all and then realised he was serious. I looked at the pictures, and it wasn't Jes.

Once, Jes's father looked him up on the internet and found that "Jeremy Wilkins, television producer" was referenced on Google more than 70,000 times. There was talk that he was a "lookout" for Gerry and Kate; there was talk that Jes was orchestrating a reality-TV hoax and Madeleine's disappearance was part of the con; there was talk that the Tapas Nine were all swingers. There was a lot of talk.

In early September, Kate and Gerry became official suspects. Their warm tide of support turned decidedly cool. Had they cruelly conned us all? The public needed to know, and who had seen Gerry at around 9pm on the fateful night? Jes.

Tonight with Trevor McDonald, GMTV, the Sun, the News of the World, the Sunday Mirror, the Daily Express, the Evening Standard and the Independent on Sunday began calling. Jes's office stopped putting through calls from people asking to speak to "Jeremy" (only his grandmother calls him that). Some emails told him that he would be "better off" if he spoke to them or he would "regret it" if he didn't, implying that it was in his interest to defend himself - they didn't say what from.

Quietly, we began to worry that Jes might be next in line for some imagined blame or accusation. On a Saturday night in September, he received a call: we were on the front page of the News of the World. They had surreptitiously taken photographs of us, outside the house. There were no more details. We went to bed, but we could not sleep. "Maddie: the secret witness," said the headline, "TV boss holds vital clue to the mystery." Unfortunately, Jes does not hold any such vital clues. In November, he inched through the events of that May night with Leicestershire detectives, but he saw nothing suspicious, nothing that would further the investigation.

Throughout all this, I have always believed that Gerry and Kate McCann are innocent. When they were made suspects, when they were booed at, when one woman told me she was "glad" they had "done it" because it meant that her child was safe, I began to write this article - because I was there, and I believe that woman is wrong. There were no drug-fuelled "swingers" on our holiday; instead, there was a bunch of ordinary parents wearing Berghaus and worrying about sleep patterns. Secure in our banality, none of us imagined we were being watched. One group made a disastrous decision; Madeleine was vulnerable and was chosen. But in the face of such desperate audacity, it could have been any one of us.

And when I stroke my daughter's hair, or feel her butterfly lips on my cheek, I do so in the knowledge of what might have been. But our experience is nothing, an irrelevance, next to the McCanns' unimaginable grief. Their lives will always be touched by this darkness, while the true culprit may never be brought to light.

So my heart goes out to them, Gerry and Kate, the couple we remember from our Portuguese holiday. They had a beautiful daughter, Madeleine, who played and danced with ours at the kiddie club. That's who we remember.

Bridget O'Donnell 2007.

Bridget O'Donnell 2007.

· Bridget O'Donnell is a writer and director. The fee from this article will be donated to the Find Madeleine fund (findmadeleine.com).

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/dec/14/ukcrime.madeleinemccann

By Bridget O'Donnell

Fri 14 Dec 2007 11.54 GMT

It was a welcome spring break, a chance to relax at a child-friendly resort in Portugal. Soon Bridget O'Donnell and her partner were making friends with another holidaying family while their three-year-old daughters played together. But then Madeleine McCann went missing and everyone was sucked into a nightmare

We lay by the members-only pool staring at the sky. Round and round, the helicopters clacked and roared. Their cameras pointed down at us, mocking the walled and gated enclave. Circles rippled out across the pool. It was the morning after Madeleine went.

Six days earlier we had landed at Faro airport. The coach was full of people like us, parents lugging multiple toddler/baby combinations. All of us had risen at dawn, rushed along motorways and hurtled across the sky in search of the modern solution to our exhaustion - the Mark Warner kiddie club. I travelled with my partner Jes, our three-year-old daughter, and our nine-month-old baby son. Praia da Luz was the nearest Mark Warner beach resort and this was the cheapest week of the year - a bargain bucket trip, for a brief lie-down.

Excitedly, we were shown to our apartments. Ours was on the fourth floor, overlooking a family and toddler pool, opposite a restaurant and bar called the Tapas. I worried about the height of the balcony. Should we ask for one on the ground floor? Was I a paranoid parent? Should I make a fuss, or just enjoy the view?

We could see the beach and a big blue sky. We went outside to explore.

We settled in over the following days. There was a warm camaraderie among the parents, a shared happy weariness and deadpan banter. Our children made friends in the kiddie club and at the drop-off, we would joke about the fact that there were 10 blonde three-year-old girls in the group. They were bound to boss around the two boys.

The children went sailing and swimming, played tennis and learned a dance routine for the end-of-week show. Each morning, our daughter ran ahead of us to get to the kiddie club. She was having a wonderful time. Jes signed up for tennis lessons. I read a book. He made friends. I read another book.

The Mark Warner nannies brought the children to the Tapas restaurant to have tea at the end of each day. It was a friendly gathering. The parents would stand and chat by the pool. We talked about the children, about what we did at home. We were hopeful about a change in the weather. We eyed our children as they played. We didn't see anyone watching.

Some of the parents were in a larger group. Most of them worked for the NHS and had met many years before in Leicestershire. Now they lived in different parts of the UK, and this holiday was their opportunity to catch up, to introduce their children, to reunite. They booked a large table every night in the Tapas. We called them "the Doctors". Sometimes we would sit out on our balcony and their laughter would float up around us. One man was the joker. He had a loud Glaswegian accent. He was Gerry McCann. He played tennis with Jes.

One morning, I saw Gerry and his wife Kate on their balcony, chatting to their friends on the path below. Privately I was glad we didn't get their apartment. It was on a corner by the road and people could see in. They were exposed.

In the evenings, babysitting at the resort was a dilemma. "Sit-in" babysitters were available but were expensive and in demand, and Mark Warner blurb advised us to book well in advance. The other option was the babysitting service at the kiddie club, which was a 10-minute walk from the apartment. The children would watch a cartoon together and then be put to bed. You would then wake them, carry them back and put them to bed again in the apartment. After taking our children to dinner a couple of times, we decided on the Wednesday night to try the service at the club.

We had booked a table for two at Tapas and were placed next to the Doctors' regular table. One by one, they started to arrive. The men came first. Gerry McCann started chatting across to Jes about tennis. Gerry was outgoing, a wisecracker, but considerate and kind, and he invited us to join them. We discussed the children. He told us they were leaving theirs sleeping in the apartments. While they chatted on, I ruminated on the pros and cons of this. I admired them, in a way, for not being paranoid parents, but I decided that our apartment was too far off even to contemplate it. Our baby was too young and I would worry about them waking up.

My phone rang as our food arrived; our baby had woken up. I walked the round trip to collect him from the kiddie club, then back to the restaurant. He kept crying and eventually we left our meal unfinished and walked back again to the club to fetch our sleeping daughter. Jes carried her home in a blanket. The next night we stayed in. It was Thursday, May 3.

Earlier that day there had been tennis lessons for the children, with some of the parents watching proudly as their girls ran across the court chasing tennis balls. They took photos. Madeleine must have been there, but I couldn't distinguish her from the others. They all looked the same - all blonde, all pink and pretty.

Jes and Gerry were playing on the next court. Afterwards, we sat by the pool and Gerry and Kate talked enthusiastically to the tennis coach about the following day's tournament. We watched them idly - they had a lot of time for people, they listened. Then Gerry stood up and began showing Kate his new tennis stroke. She looked at him and smiled. "You wouldn't be interested if I talked about my tennis like that," Jes said to me. We watched them some more. Kate was calm, still, quietly beautiful; Gerry was confident, proud, silly, strong. She watched his boyish demonstration with great seriousness and patience. That was the last time I saw them that day. Jes saw Gerry that night.

Our baby would not sleep and at about 8.30pm, Jes took him out for a walk in the buggy to settle him. Gerry was on his way back from checking on his children and the two men stopped to have a chat. They talked about daughters, fathers, families. Gerry was relaxed and friendly. They discussed the babysitting dilemmas at the resort and Gerry said that he and Kate would have stayed in too, if they had not been on holiday in a group. Jes returned to our apartment just before 9.30pm. We ate, drank wine, watched a DVD and then went to bed. On the ground floor, a completely catastrophic event was taking place. On the fourth floor of the next block, we were completely oblivious.

At 1am there was a frantic banging on our door. Jes got up to answer. I stayed listening in the dark. I knew it was bad; it could only be bad. I heard male mumbling, then Jes's voice. "You're joking?" he said. It wasn't the words, it was the tone that made me flinch. He came back in to the room. "Gerry's daughter's been abducted," he said. "She ..." I jumped up and went to check our children. They were there. We sat down. We got up again. Weirdly, I did the washing-up. We wondered what to do. Jes had asked if they needed help searching and was told there was nothing he could do; she had been missing for three hours. Jes felt he should go anyway, but I wanted him to stay with us. I was a coward, afraid to be alone with the children - and afraid to be alone with my thoughts.

I once worked as a producer in the BBC crime unit. I directed many reconstructions and spent my second pregnancy producing new investigations for Crimewatch. Detectives would call me daily, detailing their cases, and some stories stay with me still, such as the ones about a girl being snatched from her bath, or her bike, or her garden and then held in the passenger seat, or stuffed in the boot. There was always a vehicle, and the first few hours were crucial to the outcome. Afterwards, they would be dumped naked in an alley, or at a petrol station with a £10 note to "get a cab back to Mummy". They would be found within an hour or two. Sometimes.

From the balcony we could see some figures scratching at the immense darkness with tiny torch lights. Police cars arrived and we thought that they would take control. We lay on the bed but we could not sleep.

The next morning, we made our way to breakfast and met one of the Doctors, the one who had come round in the night. His young daughter looked up at us from her pushchair. There was no news. They had called Sky television - they didn't know what else to do. He turned away and I could see he was going to weep.

People were crying in the restaurant. Mark Warner had handed out letters informing them what had happened in the night, and we all wondered what to do. Mid-sentence, we would drift in to the middle distance. Tears would brim up and recede.

Our daughter asked us about the kiddie club that day. She had been looking forward to their dance show that afternoon. Jes and I looked at each other. My first instinct was that we should not be parted from our children. Of course we shouldn't; we should strap them to us and not let them out of our sight, ever again. But then we thought: how are we going to explain this to our daughter? Or how, if we spent the day in the village, would we avoid repeatedly discussing what had happened in front of her as we met people on the streets? What does a good parent do? Keep the children close or take a deep breath and let them go a little, pretend this was the same as any other day?

We walked towards the kiddie club. No one else was there. We felt awful, such terrible parents for even considering the idea. Then we saw, waiting inside, some of the Mark Warner nannies. They had been up most of the night but had still turned up to work that day. They were intelligent, thoughtful young women and we liked and trusted them. The dance show was cancelled, but they wanted to put on a normal day for the children. Our daughter ran inside and started painting. Then, behind us, another set of parents arrived looking equally washed out. Then another, and another. We decided, in the end, to leave them for two hours. We put their bags on the pegs and saw the one labelled "Madeleine". Heads bent, we walked away, into the guilty glare of the morning sun.

Locals and holidaymakers had started circulating photocopied pictures of Madeleine, while others continued searching the beaches and village apartments. People were talking about what had happened or sat silently, staring blankly. We didn't see any police.

Later, there was a knock on our apartment door and we let the two men in. One was a uniformed Portuguese policeman, the other his translator. The translator had a squint and sweated slightly. He was breathless, perhaps a little excited. We later found out he was Robert Murat. He reminded me of a boy in my class at school who was bullied.

Through Murat we answered a few questions and gave our details, which the policeman wrote down on the back of a bit of paper. No notebook. Then he pointed to the photocopied picture of Madeleine on the table. "Is this your daughter?" he asked. "Er, no," we said. "That's the girl you are meant to be searching for." My heart sank for the McCanns.

As the day drew on, the media and more police arrived and we watched from our balcony as reporters practised their pieces to camera outside the McCanns' apartment. We then went back inside and watched them on the news.

We had to duck under the police tape with the pushchair to buy a pint of milk. We would roll past sniffer dogs, local police, then national police, local journalists, and then international journalists, TV reporters and satellite vans. A hundred pairs of eyes and a dozen cameras silently swivelled as we turned down the bend. We pretended, for the children's sake, that this was nothing unusual. Later on, our daughter saw herself with Daddy on TV. That afternoon we sat by the members-only pool, watching the helicopters watching us. We didn't know what else to do.

Saturday came, our last day. While we waited for the airport coach to pick us up, we gathered round the toddler pool by Tapas, making small talk in front of the children. I watched my baby son and daughter closely, shamefully grateful that I could.

We had not seen the McCanns since Thursday, when suddenly they appeared by the pool. The surreal limbo of the past two days suddenly snapped back into painful, awful realtime. It was a shock: the physical transformation of these two human beings was sickening - I felt it as a physical blow. Kate's back and shoulders, her hands, her mouth had reshaped themselves in to the angular manifestation of a silent scream. I thought I might cry and turned so that she wouldn't see. Gerry was upright, his lips now drawn into a thin, impenetrable line. Some people, including Jes, tried to offer comfort. Some gave them hugs. Some stared at their feet, words eluding them. We all wondered what to do. That was the last time we saw Gerry and Kate.

The rest of us left Praia da Luz together, an isolated Mark Warner group. The coach, the airport, the plane passed quietly. There were no other passengers except us. We arrived at Gatwick in the small hours of an early May morning. No jokes, no banter, just goodbye. Though we did not know it then, those few days in May were going to dominate the rest of our year.

"Did you have a good trip?" asked the cabbie at Gatwick, instantly underlining the conversational dilemma that would occupy the first few weeks: Do we say "Yes, thanks" and move swiftly on? Or divulge the "yes-but-no-but" truth of our "Maddy" experience? Everybody talks about holidays, they make good conversational currency at work, at the hairdresser's, in the playground. Everybody asked about ours. I would pause and take a breath, deciding whether there was enough time for what was to follow. People were genuinely horrified by what had happened to Madeleine and even by what we had been through (though we thought ourselves fortunate). Their humanity was a balm and a comfort to us; we needed to talk about it, chew it over and share it out, to make it a little easier to swallow.

The British police came round shortly after our return. Jes was pleased to give them a statement. The Portuguese police had never asked.

As the summer months rolled by, we thought the story would slowly and sadly ebb away, but instead it flourished and multiplied, and it became almost impossible to talk about any-thing else. Friends came for dinner and we would actively try to steer the conversation on to a different subject, always to return to Madeleine. Others solicited our thoughts by text message after any major twist or turn in the case. Acquaintances discussed us in the context of Madeleine, calling in the middle of their debates to clarify details.

I found some immunity in a strange, guilty happiness. We had returned unscathed to our humdrum family routine, my life was wonderful, my world was safe, I was lucky, I was blessed. The colours in the park were acute and hyper-real and the sun warmed my face.

At the end of June, the first cloud appeared. A Portuguese journalist called Jes's mobile (he had left his number with the Portuguese police). The journalist, who was writing for a magazine called Sol, called Jes incessantly. We both work in television and cannot claim to be green about the media, but this was a new experience. Jes learned this the hard way. Torn between politeness and wanting to get the journalist off the line without actually saying anything, he had to put the phone down, but he had already said too much. Her article pitched the recollections of "Jeremy Wilkins, television producer" against those of the "Tapas Nine", the group of friends, including the McCanns, whom we had nicknamed the Doctors. The piece was published at the end of June. Throughout July, Sol's testimony meant Jes became incorporated into all the Madeleine chronologies. More clouds began to gather - this time above our house.

In August, the doorbell rang. The man was from the Daily Mail. He asked if Jes was in (he wasn't). After he left I spent an anxious evening analysing what I had said, weighing up the possible consequences. The Sol article had brought the Daily Mail; what would happen next? Two days later, the Mail came for Jes again. This time they had computer printout pictures of a bald, heavy-set man seen lurking in some Praia da Luz holiday snaps. The chatroom implication was that the man was Madeleine's abductor. There was talk on the web, the reporter insinuated, that this man might be Jes. I laughed at the ridiculousness of it all and then realised he was serious. I looked at the pictures, and it wasn't Jes.

Once, Jes's father looked him up on the internet and found that "Jeremy Wilkins, television producer" was referenced on Google more than 70,000 times. There was talk that he was a "lookout" for Gerry and Kate; there was talk that Jes was orchestrating a reality-TV hoax and Madeleine's disappearance was part of the con; there was talk that the Tapas Nine were all swingers. There was a lot of talk.

In early September, Kate and Gerry became official suspects. Their warm tide of support turned decidedly cool. Had they cruelly conned us all? The public needed to know, and who had seen Gerry at around 9pm on the fateful night? Jes.

Tonight with Trevor McDonald, GMTV, the Sun, the News of the World, the Sunday Mirror, the Daily Express, the Evening Standard and the Independent on Sunday began calling. Jes's office stopped putting through calls from people asking to speak to "Jeremy" (only his grandmother calls him that). Some emails told him that he would be "better off" if he spoke to them or he would "regret it" if he didn't, implying that it was in his interest to defend himself - they didn't say what from.

Quietly, we began to worry that Jes might be next in line for some imagined blame or accusation. On a Saturday night in September, he received a call: we were on the front page of the News of the World. They had surreptitiously taken photographs of us, outside the house. There were no more details. We went to bed, but we could not sleep. "Maddie: the secret witness," said the headline, "TV boss holds vital clue to the mystery." Unfortunately, Jes does not hold any such vital clues. In November, he inched through the events of that May night with Leicestershire detectives, but he saw nothing suspicious, nothing that would further the investigation.

Throughout all this, I have always believed that Gerry and Kate McCann are innocent. When they were made suspects, when they were booed at, when one woman told me she was "glad" they had "done it" because it meant that her child was safe, I began to write this article - because I was there, and I believe that woman is wrong. There were no drug-fuelled "swingers" on our holiday; instead, there was a bunch of ordinary parents wearing Berghaus and worrying about sleep patterns. Secure in our banality, none of us imagined we were being watched. One group made a disastrous decision; Madeleine was vulnerable and was chosen. But in the face of such desperate audacity, it could have been any one of us.

And when I stroke my daughter's hair, or feel her butterfly lips on my cheek, I do so in the knowledge of what might have been. But our experience is nothing, an irrelevance, next to the McCanns' unimaginable grief. Their lives will always be touched by this darkness, while the true culprit may never be brought to light.

So my heart goes out to them, Gerry and Kate, the couple we remember from our Portuguese holiday. They had a beautiful daughter, Madeleine, who played and danced with ours at the kiddie club. That's who we remember.

· Bridget O'Donnell is a writer and director. The fee from this article will be donated to the Find Madeleine fund (findmadeleine.com).

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/dec/14/ukcrime.madeleinemccann

Guest- Guest

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

He's disgusting. He has insulted those who never have, and never will, do what the McCann's did, dining while the children were left to fend for themselves. What a bastard.

CaKeLoveR- Forum support

- Posts : 4998

Activity : 5062

Likes received : 72

Join date : 2022-02-19

maebee and sparkyhorrox like this post

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Re: Madeleine McCann: Media Commentary

Unanswered Prayers

After three-year-old Madeleine McCann disappeared on a family vacation in Portugal, her parents pursued a high-stakes strategy: media saturation. It succeeded beyond their wildest imaginings—winning the aid of everyone from J. K. Rowling to the Pope—and failed miserably. Getting the first in-depth interview with Gerry McCann since he and his wife, Kate, were declared suspects, the author re-traces their footsteps to their daughter’s empty bed.

By Judy Bachrach

January 10, 2008

On a hot day last September, four months after their daughter, Madeleine, almost four, vanished from a sleepy resort town in Portugal during a family vacation, Kate and Gerry McCann, both British doctors, opened their villa door to a local policeman.

The policeman’s name was Ricardo, and he had been, relatively speaking, on friendly terms with the couple. He knew their circumstances. Their lives, heavy with grief since their daughter’s disappearance, had undergone a few small improvements. Kate had grown shockingly thin, but at least she was eating regular meals.