One or two interesting parallels

Page 1 of 1 • Share

One or two interesting parallels

One or two interesting parallels

Everyone focussing in the wrong direction. Reviews made assumptions. Endless false sightings, Possible suspect discounted early on, Fantasist,

Telegraph

How a piece of Sellotape unlocked one of Britain’s most notorious cold cases

Rikki Neave’s murder dominated headlines in 1994, but his killer wasn’t brought to justice – until a detective took a fresh look at his coat

ByCharlotte Lytton

29 April 2022 • 5:00am

A year after the horrific murder of Jamie Bulger, Rikki’s death meant pressure was on the police to ensure another child killer wasn’t walking the streets.

A 28-year-old piece of Sellotape brought one of Britain’s most notorious cold cases to a close last week. The ‘taping’, pressed on to the coat of six-year-old Rikki Neave and stored in an archive decades ago, picked up fibres that would ultimately be linked to James Watson, then 13, who followed the younger boy into a Peterborough woodland in 1994 – and strangled him from behind with the zip of his coat. Watson had then allegedly stripped Neave naked and arranged him in a star pose, possibly for his own “sexual gratification”.

Justice was served just days ago when Watson was found guilty of murder in “the most complex and challenging investigation that I’ve ever been involved in,” says Paul Fullwood, former assistant chief constable for Cambridgeshire Police and senior lead investigator. A “career detective,” Fullwood – who retired in 2020, but sat in the Old Bailey every day of this year’s three-month trial – is “very, very proud of the outcome”.

The case had dominated news headlines at the time. A year after the horrific murder of Jamie Bulger, Rikki’s death meant pressure was on the police to ensure another child killer wasn’t walking the streets. The case became more “iconic” still when Ruth Neave, the boy’s mother, was charged with murder and child cruelty six months later. Neave was sentenced to seven years in prison following a highly public trial that painted a harrowing picture of life on the Welland Estate for Rikki – classified as “at-risk” by social services – and his sisters, who were routinely abused by their “wholly unfit” mother. Following another trial in 1996, the murder charge was rescinded and she was released in 2000.

Had Neave’s treatment of her son not been so brutal, Rikki’s case could have looked very different, Fullwood, 52, believes. The murder “should have been reviewed a lot more times” than it was, he says, but the fact that Neave was behind the push to reinvestigate held things back, as even though she had been acquitted “there was always a feeling around this case that Ruth may have done it”.

Fullwood adds that many were “uneasy around potential reinvestigation of this case, because this brought back a lot of bad memories for lots and lots of people – there was still a little bit of unconscious bias”. Had she not remained so inextricably linked with child cruelty in both officers’ and public minds – a mother convicted of scrawling “idiot” across her son's head, squirting washing up liquid in his mouth and beating her children – “then there might have been a different outcome”.

His own involvement began eight years ago, when Fullwood agreed to meet Neave, now 53, and her partner at Parkside Police Station in Cambridge. He went “with a completely open mind because I was never involved in the original investigation... I had no baggage”. He agreed to conduct a proper review and, five months later, Fullwood was confident that reopening the case could secure a conviction. In June 2015, a press conference and public appeal launched Operation Mansell, with a further call for information broadcast on BBC Crimewatch five months later.

Reopening the case meant two main hurdles: combing through the oceans of information a public case yields, such as 15,000 documents and endless false sightings, and handling decades-old evidence – much of which had either been destroyed or returned to the family in the mid-Nineties. Almost everything was gone, Rikki’s body cremated; DNA detection “wasn’t even on the radar” by the time of his murder. But digging through the forensic archives found papers, “and within the papers were envelopes, and within the envelopes were Sellotape tapings,” Fullwood remembers.

Using modern forensic techniques, foreign fibres from those tapings were found to match Watson’s, a “billion to one”. But that alone could not be enough to convict him.

However, Watson’s name had already been identified by Mansell officers as one of many needing “more thorough” questioning than they had originally received in 1994.

Indeed, letting him slip through the net was one of a litany of issues with the original case. “I think it was tricky for them because they discounted James Watson early doors. They discounted him very, very quickly. And a lot of the focus was on Ruth Neave. And I think that took them down the wrong path,” Fullwood says of the “tunnel vision” that reigned among investigating officers in 1994.

He says that it was only in 2013 that “we really professionalised major crime”; that now, murders like Rikki’s being handled by local detectives, rather than experts further afield, would never happen. “It was a different era. We are far better trained now and far more experienced… [the officers] tried to do the best job they could at the time with the people that they had. I just think that they made the wrong decisions.”

That “cracked trial” almost 30 years ago saw hard lessons learnt, Fullwood adds, along with the sacking of social services staff who had failed to protect Rikki and his sisters.

Fullwood believes that the focus on Rikki's mother, Ruth Neave, gave the police officers ‘tunnel vision’

By 2016, Operation Mansell led to the arrest of Watson on suspicion of murder. Already a serial offender, he was bailed and fled to Portugal, posting photos of himself on the beach and bragging to local papers about how easily he had fled. The Crown Prosecution Service had told Watson that no further action would likely be taken against him due to a lack of evidence, but Fullwood urged the Neaves to appeal via the Victims Right to Review scheme, which they won, with the murder charge issued in February 2020. Due to legal issues and Covid delays, the trial began at the Old Bailey in January this year.

Last Thursday was a particularly challenging day in court for Fullwood, who has “built my entire retirement around this case”. Watson – who has been charged with other offences including sexually assaulting a man in 2018 – appeared in court every day except the trial’s conclusion. His insistence on providing “evidence” – such as references to a fence that didn’t exist, or stating that his father had been an officer with Cambridgeshire police – only further cemented Fullwood’s belief that “he’s a dangerous, manipulative individual”; one who “tried to be one step ahead of the police” in a bid to “escape and evade justice”.

The more Watson spoke, the more of a “fantasist” he made himself out to be, Fullwood says. “I was convinced before, but even more convinced listening to his evidence.”

It had been a mammoth three months featuring 151 witnesses, which is “unheard of”, Fullwood says, pointing out that the case became a cause celebre again as “there aren’t many cases in UK policing history where you have a murder trial, the mother charged with a murder, then acquitted, then we as the police coming back again saying we’re going to try and re-investigate it. And we come up with completely different suspects.” Around three times bigger than the average murder investigation, he says Rikki’s case is second only in complexity to “the very, very tragic case of Soham”, in which 10-year-olds Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman were killed in 2002.

Extensive deliberations in court had left Fullwood expecting a hung jury; he began contingency planning, mooting a retrial in April 2023, preparing to call the family with news that the outcome may be bad and phoning senior people in the CPS to let them know that there was “absolutely no doubt… we would have [gone to court] again, and again, and again”.

Paul Fullwood retired in 2020, but sat in the Old Bailey every day of this year’s three-month trial

During deliberations, Fullwood was walking down the Millennium Bridge to clear his head when his phone began buzzing: the verdict was about to be read. When they announced they had found Watson, 41, guilty, Fullwood grabbed the leg of the senior officer next to him: “We were all in disbelief and amazement that we finally got there.” Watson had been absent in the morning but appeared that afternoon via video link from Belmarsh prison, and “didn’t flinch” at the verdict, Fullwood remembers of those “surreal” few moments. (Watson will be sentenced on May 9.)

The next day, he met Ruth Neave, who is suffering ill health and had been watching the proceedings via a video link, at the police station, where she hugged Fullwood and thanked him for finally bringing justice for her son. Her three daughters, who do not have a relationship with their mother, shared their relief privately with him, too. While he is thrilled to “bring some sort of closure” to the Neave family, Fullwood’s last hope for this case is that Watson’s conviction may bring about reconciliation.

“They may never ever be a perfect family, they may never ever be a harmonious family,” he says. “But there might be some middle ground there.”

Telegraph

How a piece of Sellotape unlocked one of Britain’s most notorious cold cases

Rikki Neave’s murder dominated headlines in 1994, but his killer wasn’t brought to justice – until a detective took a fresh look at his coat

ByCharlotte Lytton

29 April 2022 • 5:00am

A year after the horrific murder of Jamie Bulger, Rikki’s death meant pressure was on the police to ensure another child killer wasn’t walking the streets.

A 28-year-old piece of Sellotape brought one of Britain’s most notorious cold cases to a close last week. The ‘taping’, pressed on to the coat of six-year-old Rikki Neave and stored in an archive decades ago, picked up fibres that would ultimately be linked to James Watson, then 13, who followed the younger boy into a Peterborough woodland in 1994 – and strangled him from behind with the zip of his coat. Watson had then allegedly stripped Neave naked and arranged him in a star pose, possibly for his own “sexual gratification”.

Justice was served just days ago when Watson was found guilty of murder in “the most complex and challenging investigation that I’ve ever been involved in,” says Paul Fullwood, former assistant chief constable for Cambridgeshire Police and senior lead investigator. A “career detective,” Fullwood – who retired in 2020, but sat in the Old Bailey every day of this year’s three-month trial – is “very, very proud of the outcome”.

The case had dominated news headlines at the time. A year after the horrific murder of Jamie Bulger, Rikki’s death meant pressure was on the police to ensure another child killer wasn’t walking the streets. The case became more “iconic” still when Ruth Neave, the boy’s mother, was charged with murder and child cruelty six months later. Neave was sentenced to seven years in prison following a highly public trial that painted a harrowing picture of life on the Welland Estate for Rikki – classified as “at-risk” by social services – and his sisters, who were routinely abused by their “wholly unfit” mother. Following another trial in 1996, the murder charge was rescinded and she was released in 2000.

Had Neave’s treatment of her son not been so brutal, Rikki’s case could have looked very different, Fullwood, 52, believes. The murder “should have been reviewed a lot more times” than it was, he says, but the fact that Neave was behind the push to reinvestigate held things back, as even though she had been acquitted “there was always a feeling around this case that Ruth may have done it”.

Fullwood adds that many were “uneasy around potential reinvestigation of this case, because this brought back a lot of bad memories for lots and lots of people – there was still a little bit of unconscious bias”. Had she not remained so inextricably linked with child cruelty in both officers’ and public minds – a mother convicted of scrawling “idiot” across her son's head, squirting washing up liquid in his mouth and beating her children – “then there might have been a different outcome”.

His own involvement began eight years ago, when Fullwood agreed to meet Neave, now 53, and her partner at Parkside Police Station in Cambridge. He went “with a completely open mind because I was never involved in the original investigation... I had no baggage”. He agreed to conduct a proper review and, five months later, Fullwood was confident that reopening the case could secure a conviction. In June 2015, a press conference and public appeal launched Operation Mansell, with a further call for information broadcast on BBC Crimewatch five months later.

Reopening the case meant two main hurdles: combing through the oceans of information a public case yields, such as 15,000 documents and endless false sightings, and handling decades-old evidence – much of which had either been destroyed or returned to the family in the mid-Nineties. Almost everything was gone, Rikki’s body cremated; DNA detection “wasn’t even on the radar” by the time of his murder. But digging through the forensic archives found papers, “and within the papers were envelopes, and within the envelopes were Sellotape tapings,” Fullwood remembers.

Using modern forensic techniques, foreign fibres from those tapings were found to match Watson’s, a “billion to one”. But that alone could not be enough to convict him.

However, Watson’s name had already been identified by Mansell officers as one of many needing “more thorough” questioning than they had originally received in 1994.

Indeed, letting him slip through the net was one of a litany of issues with the original case. “I think it was tricky for them because they discounted James Watson early doors. They discounted him very, very quickly. And a lot of the focus was on Ruth Neave. And I think that took them down the wrong path,” Fullwood says of the “tunnel vision” that reigned among investigating officers in 1994.

He says that it was only in 2013 that “we really professionalised major crime”; that now, murders like Rikki’s being handled by local detectives, rather than experts further afield, would never happen. “It was a different era. We are far better trained now and far more experienced… [the officers] tried to do the best job they could at the time with the people that they had. I just think that they made the wrong decisions.”

That “cracked trial” almost 30 years ago saw hard lessons learnt, Fullwood adds, along with the sacking of social services staff who had failed to protect Rikki and his sisters.

Fullwood believes that the focus on Rikki's mother, Ruth Neave, gave the police officers ‘tunnel vision’

By 2016, Operation Mansell led to the arrest of Watson on suspicion of murder. Already a serial offender, he was bailed and fled to Portugal, posting photos of himself on the beach and bragging to local papers about how easily he had fled. The Crown Prosecution Service had told Watson that no further action would likely be taken against him due to a lack of evidence, but Fullwood urged the Neaves to appeal via the Victims Right to Review scheme, which they won, with the murder charge issued in February 2020. Due to legal issues and Covid delays, the trial began at the Old Bailey in January this year.

Last Thursday was a particularly challenging day in court for Fullwood, who has “built my entire retirement around this case”. Watson – who has been charged with other offences including sexually assaulting a man in 2018 – appeared in court every day except the trial’s conclusion. His insistence on providing “evidence” – such as references to a fence that didn’t exist, or stating that his father had been an officer with Cambridgeshire police – only further cemented Fullwood’s belief that “he’s a dangerous, manipulative individual”; one who “tried to be one step ahead of the police” in a bid to “escape and evade justice”.

The more Watson spoke, the more of a “fantasist” he made himself out to be, Fullwood says. “I was convinced before, but even more convinced listening to his evidence.”

It had been a mammoth three months featuring 151 witnesses, which is “unheard of”, Fullwood says, pointing out that the case became a cause celebre again as “there aren’t many cases in UK policing history where you have a murder trial, the mother charged with a murder, then acquitted, then we as the police coming back again saying we’re going to try and re-investigate it. And we come up with completely different suspects.” Around three times bigger than the average murder investigation, he says Rikki’s case is second only in complexity to “the very, very tragic case of Soham”, in which 10-year-olds Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman were killed in 2002.

Extensive deliberations in court had left Fullwood expecting a hung jury; he began contingency planning, mooting a retrial in April 2023, preparing to call the family with news that the outcome may be bad and phoning senior people in the CPS to let them know that there was “absolutely no doubt… we would have [gone to court] again, and again, and again”.

Paul Fullwood retired in 2020, but sat in the Old Bailey every day of this year’s three-month trial

During deliberations, Fullwood was walking down the Millennium Bridge to clear his head when his phone began buzzing: the verdict was about to be read. When they announced they had found Watson, 41, guilty, Fullwood grabbed the leg of the senior officer next to him: “We were all in disbelief and amazement that we finally got there.” Watson had been absent in the morning but appeared that afternoon via video link from Belmarsh prison, and “didn’t flinch” at the verdict, Fullwood remembers of those “surreal” few moments. (Watson will be sentenced on May 9.)

The next day, he met Ruth Neave, who is suffering ill health and had been watching the proceedings via a video link, at the police station, where she hugged Fullwood and thanked him for finally bringing justice for her son. Her three daughters, who do not have a relationship with their mother, shared their relief privately with him, too. While he is thrilled to “bring some sort of closure” to the Neave family, Fullwood’s last hope for this case is that Watson’s conviction may bring about reconciliation.

“They may never ever be a perfect family, they may never ever be a harmonious family,” he says. “But there might be some middle ground there.”

____________________

PeterMac's FREE e-book

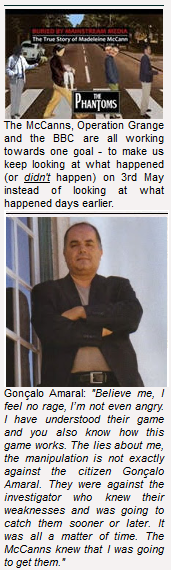

Gonçalo Amaral: The truth of the lie

CMOMM & MMRG Blog

MAGA

MAGA

MBGA

MBGA

Re: One or two interesting parallels

Re: One or two interesting parallels

It's a shame that a case which is investigated 'as though it took place in the U.K.' isn't included.

CaKeLoveR- Forum support

- Posts : 5001

Activity : 5065

Likes received : 72

Join date : 2022-02-19

Similar topics

Similar topics» LISA IRWIN, 10 months: parents make tearful plea - AND - Aaliyah Lunsford, missing in U.S., aged 3: LATEST

» The contradictions in the evidence of Leonor Cipriano - and a summary of her 15 lies in court

» Uncanny parallels

» Uncanny parallels: Huntley -v- McCann

» Some disturbing parallels: Study finds psychopaths, narcissists, sadists and others all share a 'dark core' of humanity

» The contradictions in the evidence of Leonor Cipriano - and a summary of her 15 lies in court

» Uncanny parallels

» Uncanny parallels: Huntley -v- McCann

» Some disturbing parallels: Study finds psychopaths, narcissists, sadists and others all share a 'dark core' of humanity

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum