The coalescence of journalism and PR in cases like that of Madeleine McCann

Page 1 of 1 • Share

The coalescence of journalism and PR in cases like that of Madeleine McCann

The coalescence of journalism and PR in cases like that of Madeleine McCann

Spin, spin, spin, spin...see highlighted passages below:

We are all in PR now

As journalism flounders, public relations continues to thrive. But

that’s good news for both sides of the divide, argues a PR academic.

It is time to admit that the two disciplines of journalism and PR are two sides of the same coin and that there is now complete freedom of movement between them. What’s more, with PR generally being better remunerated and flourishing, whereas journalism – print and broadcast – seems to be in a constant state of crisis, has public relations emerged from being seen by journalism as a poor and distant relation to taking on the role of a rich and

powerful cousin?

With the continuing growth of jobs in the PR industry – in business, politics, government and with exploding demand for PR online – more and more students who might have been attracted to journalism courses are now opting for PR degrees. Drawn to London, as the centre of European media, they arrive in increasing numbers from all over the world. At Westminster University, some 65 per cent of undergraduate PR students are foreign. In

the MA (PR) course this year, that figure is 100 per cent.

A typical undergraduate applicant is approximately 18 years old, female, and from a

Middle Eastern or former Soviet state. She has zero knowledge of, or prior interest in, the British media, the pool in which she must learn to swim if she is to win her degree, let alone become a successful practitioner. At some point early in the first semester, our student, failing to understand the nuanced persuasion of gift bags, drinks, or a day at the tennis, asks: “Why not just pay them to write our story?”

To help sort out such confusion, public relations courses on offer need journalism as their stablemate. PR students benefit from taking journalism classes, learning to report and write, and hearing from teachers who know the media’s daily routine and requirements intimately, while witnessing their continuing efforts to instill integrity. No one else has the authority – and credibility – of a tutor who has done time on the beat.

It is equally true that today’s young journalist, schooled at university, will deal with public relations operators many times in the normal course of a day – for her entire career – whether she likes it or not. In this world of mutual dependency, some formal study of the other discipline is obviously desirable, if only to appreciate the sophistry of persuasive techniques the budding newshound will encounter. But students of both disciplines will

also soon see for themselves that there are more (and better paid) entry-level jobs in public relations, and that a significant number of high-profile journalists cross over into PR. What’s more, there are journalists-turned-PRs, as well as those who started out in public relations, now occupying the public high-ground: David Cameron and Peter Mandelson come to mind.

Recently it has become a truism that “good communications, positive media relations and a proactive reputation management strategy are critical to all modern organisations in public, private, or third sectors”, says the Chartered Institute of Public Relations 2009.

From church to State to sports clubs to industry, from the socially beneficial to rapacious marketers, it is almost impossible to find an organisational exception to this rule. Bill Gates

famously said he’d spend his last dime on PR, and now all who can afford it seek intermediation when facing journalists. This astonishing fact is hardly due to the saintliness and bottom-line effectiveness of public relations per se, but more likely to the widespread conviction that the press is always out to get you, it always has an (unspoken) agenda, and there is a perceived need to try to level the playing field. An even more profoundly held belief, or fear, is that all reporters and journalists are of Jeremy Paxman-like proportions.

The lure of appearing live on television for a business or charity leader is thus undermined by a dread of looking foolish. Someone else needs to smooth the way, hand-hold, and if necessary, take the rap. And who better than an exjourno? The idea has form as shown by a galaxy of stars, from Andrew Gowers, who left editing the Financial Times to head marketing and communications for Lehman Brothers, now conspicuous in a similar role at BP, to Amanda Platell, making the more unusual return voyage from editing the Sunday

Express to political spin and then back to journalism. The list of tabloid editors crossing over to public relations – David Yelland, Stuart Higgins, Phil Hall and Andy Coulson being the more recent examples – emphasise the drift. Along with the so far exclusive Piers Morgan brand of editor-celebrity,all contribute to the new PR-journalism hybrid.

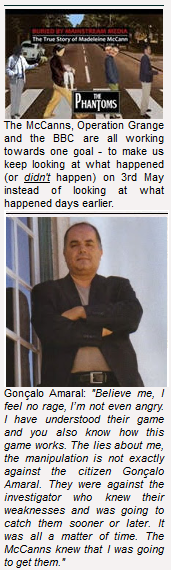

Across all sectors and embedded throughout public relations agencies – including on their boards – former press lions reap the rewards of their well-known faces and bylines. Michael Cole went from BBC TV to Harrods, from where he handled the deaths of Princess Diana and Dodi al-Fayed, victims in one of the biggest stories of the last decade, and on to set up the public relations agency Michael Cole & Company. Sir Nicholas Lloyd, former editor of the Daily Express, also started an agency whose website states: “Brown Lloyd James has unmatched personal contacts with major news editors”, and whose clients are The Daily Telegraph and The Really Useful Group, among others. Clarence Mitchell moved from BBC TV to the Foreign Office and then on via the Madeleine McCann campaign and Freud Communications to the Conservative Party, where he joined a leader and many colleagues from the public relations industry.

PR is now ‘accepted as necessary and legitimate’

Nothing new there. Governments of recent decades all used journalists turned-public relations operators to bridge both worlds at the interstices of politics. But how do these men (and fewer women) justify their new existence? What, apart from the obvious, makes them sleep at night, having jumped from the noble ship of journalism to its seamier cousin?

Here, the greatest exemplar, Alastair Campbell, provides some insight. Looking down his nose he made an expression of disgust when, in 1995, having left the Daily Mirror to become Tony Blair’s press secretary, he was welcomed to the ranks of publicists. But fast forward nine years and the legendary spin doctor told a riveted audience at the International Public Relations Association annual summit: “There is a revolution going on, a lot of it driven by 24-hour news. As the media have grown and adapted, so PR has grown and adapted. PR is now accepted as a necessary and legitimate thing to do. The problem is not with PR, the problem is with politics and spin.”

While doubtless Campbell had many reasons for his U-turn, he nevertheless illustrates a change of heart typical of those on a similar trajectory. After working in both fields, it is easy to see that journalism and PR are not so very different. Both rely on research, fact-digging, and the ability to put across the story to gain maximum impact. Whether it’s simply

relations, is introduced to PR students early, but curiously not to budding journalists unless they are taking PR modules. He repays some thinking.

Bernays, like most democrats, maintained that the efficient running of society relied on the media to argue agendas and counter-agendas. A man of strategic insight and tactical masterstrokes (think Alastair Campbell and Sir Tim Bell combined, with a dash of his distant cousin Matthew Freud), he further promulgated the beneficial social role of professional persuasion. Airing alternative and minority viewpoints that the press may overlook could change society for the greater good, he argued.

It is hard to look back dispassionately on his 1928 Torches of Freedom march in New York City to get your own by-line on the front page, or to sell more copies of your paper,

or to sell your client’s product or service, many of the same skills are required. With more and more journalists operating as freelances, add on the necessary skill to pitch to an editor and that’s exactly the same ability as PRs need – thick skin and all.

So where does this leave the student of either craft? Unlike journalism, there is a scarcity of PR literature to draw on for prospective students seeking informed opinion (in itself, unlikely) and many students apply with only a vague notion of the course on which they’re embarking. Applicants in interviews sometimes cite influencing public opinion – occasionally for social benefit – although more usually they opt for clients’ commercial gain. But few have any idea how well informed they must be if they are to be effective.

Bernays maintained that in a fractured society – one we might call multicultural today – social causes need publicity, and wrote: “Symbols need to be attached to proposals… to make them less abstract and more marketable. Circumstances need to be created to dramatize their importance and also get the attention of newspapers. The press is vitally important because newspaper coverage can re-translate these pro-social ideas so that

they become fact with [the] power to influence large bodies of people.”

Branded “the assassin of democracy” and vilified for manipulating the press, Bernays’s reputation, along with other publicists in the first half of the last century, took a direct hit after the Second World War. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter is said to have described Bernays as a “professional poisoner of the public mind, exploiter of foolishness, fanaticism and self-interest”.

His brand of public persuasion was seen as the inspiration for Nazi propaganda, and Bernays himself, acceding to this ruinous post-war view, said that effective propaganda must have, at its core, the truth: “But, it is more than that. It is also about shaping or creating events to demonstrate that truth.”

A veneer of respectability

But PR’s ability to change perception, presaged by Bernays, is now commonplace: Unilever’s resoundingly successful commercial Dove soap “Campaign for Real Beauty” and, in social marketing – with society as the beneficiary rather than the initiating organisation – anti-smoking, contraception, AIDs, and drink-driving campaigns, among countless others, give PR a veneer of social respectability. Interestingly, it is in some editorial suites that the last bastions stand, and public relations is still verboten.

Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre famously never lunches with PRs, although some of those operating on his behalf beyond his door occasionally do, even if holding their noses. Nevertheless reporters need data and contacts and publicists need reporters. It works both ways. A widespread modus operandi exists among professionals based on a shared understanding of the omnipresent pressure of an insatiable 24-hour media market. Given their proximity, the consequent growth in free movement between the two disciplines is hardly surprising.

With luck and time, the workplace reality will be reflected in higher education, particularly in journalism schools, where students facing an uncertain future could benefit from greater appreciation and integration. In its latest employment survey (March this year) recruitment specialists Reed.co.uk’s figures show that demand for those working in marketing and PR bucks the general trend and continues to rise; a glimmer of hope in an otherwise adverse story. CBI figures corroborate the finding, showing a continuing steady rise in these sectors. As professional purveyors of information, it is surely good news for those on both sides of the ancient divide that part of the market is buoyant, offering jobs for both prospective

journalism and public relations practitioners.

Trish Evans is a former journalist and PR strategist who runs the BA Public

Relations degree course at the University of Westminster, London.

Posted by British Journalism Review @ 4.02am on 5 June, 2010

We are all in PR now

As journalism flounders, public relations continues to thrive. But

that’s good news for both sides of the divide, argues a PR academic.

It is time to admit that the two disciplines of journalism and PR are two sides of the same coin and that there is now complete freedom of movement between them. What’s more, with PR generally being better remunerated and flourishing, whereas journalism – print and broadcast – seems to be in a constant state of crisis, has public relations emerged from being seen by journalism as a poor and distant relation to taking on the role of a rich and

powerful cousin?

With the continuing growth of jobs in the PR industry – in business, politics, government and with exploding demand for PR online – more and more students who might have been attracted to journalism courses are now opting for PR degrees. Drawn to London, as the centre of European media, they arrive in increasing numbers from all over the world. At Westminster University, some 65 per cent of undergraduate PR students are foreign. In

the MA (PR) course this year, that figure is 100 per cent.

A typical undergraduate applicant is approximately 18 years old, female, and from a

Middle Eastern or former Soviet state. She has zero knowledge of, or prior interest in, the British media, the pool in which she must learn to swim if she is to win her degree, let alone become a successful practitioner. At some point early in the first semester, our student, failing to understand the nuanced persuasion of gift bags, drinks, or a day at the tennis, asks: “Why not just pay them to write our story?”

To help sort out such confusion, public relations courses on offer need journalism as their stablemate. PR students benefit from taking journalism classes, learning to report and write, and hearing from teachers who know the media’s daily routine and requirements intimately, while witnessing their continuing efforts to instill integrity. No one else has the authority – and credibility – of a tutor who has done time on the beat.

It is equally true that today’s young journalist, schooled at university, will deal with public relations operators many times in the normal course of a day – for her entire career – whether she likes it or not. In this world of mutual dependency, some formal study of the other discipline is obviously desirable, if only to appreciate the sophistry of persuasive techniques the budding newshound will encounter. But students of both disciplines will

also soon see for themselves that there are more (and better paid) entry-level jobs in public relations, and that a significant number of high-profile journalists cross over into PR. What’s more, there are journalists-turned-PRs, as well as those who started out in public relations, now occupying the public high-ground: David Cameron and Peter Mandelson come to mind.

Recently it has become a truism that “good communications, positive media relations and a proactive reputation management strategy are critical to all modern organisations in public, private, or third sectors”, says the Chartered Institute of Public Relations 2009.

From church to State to sports clubs to industry, from the socially beneficial to rapacious marketers, it is almost impossible to find an organisational exception to this rule. Bill Gates

famously said he’d spend his last dime on PR, and now all who can afford it seek intermediation when facing journalists. This astonishing fact is hardly due to the saintliness and bottom-line effectiveness of public relations per se, but more likely to the widespread conviction that the press is always out to get you, it always has an (unspoken) agenda, and there is a perceived need to try to level the playing field. An even more profoundly held belief, or fear, is that all reporters and journalists are of Jeremy Paxman-like proportions.

The lure of appearing live on television for a business or charity leader is thus undermined by a dread of looking foolish. Someone else needs to smooth the way, hand-hold, and if necessary, take the rap. And who better than an exjourno? The idea has form as shown by a galaxy of stars, from Andrew Gowers, who left editing the Financial Times to head marketing and communications for Lehman Brothers, now conspicuous in a similar role at BP, to Amanda Platell, making the more unusual return voyage from editing the Sunday

Express to political spin and then back to journalism. The list of tabloid editors crossing over to public relations – David Yelland, Stuart Higgins, Phil Hall and Andy Coulson being the more recent examples – emphasise the drift. Along with the so far exclusive Piers Morgan brand of editor-celebrity,all contribute to the new PR-journalism hybrid.

Across all sectors and embedded throughout public relations agencies – including on their boards – former press lions reap the rewards of their well-known faces and bylines. Michael Cole went from BBC TV to Harrods, from where he handled the deaths of Princess Diana and Dodi al-Fayed, victims in one of the biggest stories of the last decade, and on to set up the public relations agency Michael Cole & Company. Sir Nicholas Lloyd, former editor of the Daily Express, also started an agency whose website states: “Brown Lloyd James has unmatched personal contacts with major news editors”, and whose clients are The Daily Telegraph and The Really Useful Group, among others. Clarence Mitchell moved from BBC TV to the Foreign Office and then on via the Madeleine McCann campaign and Freud Communications to the Conservative Party, where he joined a leader and many colleagues from the public relations industry.

PR is now ‘accepted as necessary and legitimate’

Nothing new there. Governments of recent decades all used journalists turned-public relations operators to bridge both worlds at the interstices of politics. But how do these men (and fewer women) justify their new existence? What, apart from the obvious, makes them sleep at night, having jumped from the noble ship of journalism to its seamier cousin?

Here, the greatest exemplar, Alastair Campbell, provides some insight. Looking down his nose he made an expression of disgust when, in 1995, having left the Daily Mirror to become Tony Blair’s press secretary, he was welcomed to the ranks of publicists. But fast forward nine years and the legendary spin doctor told a riveted audience at the International Public Relations Association annual summit: “There is a revolution going on, a lot of it driven by 24-hour news. As the media have grown and adapted, so PR has grown and adapted. PR is now accepted as a necessary and legitimate thing to do. The problem is not with PR, the problem is with politics and spin.”

While doubtless Campbell had many reasons for his U-turn, he nevertheless illustrates a change of heart typical of those on a similar trajectory. After working in both fields, it is easy to see that journalism and PR are not so very different. Both rely on research, fact-digging, and the ability to put across the story to gain maximum impact. Whether it’s simply

relations, is introduced to PR students early, but curiously not to budding journalists unless they are taking PR modules. He repays some thinking.

Bernays, like most democrats, maintained that the efficient running of society relied on the media to argue agendas and counter-agendas. A man of strategic insight and tactical masterstrokes (think Alastair Campbell and Sir Tim Bell combined, with a dash of his distant cousin Matthew Freud), he further promulgated the beneficial social role of professional persuasion. Airing alternative and minority viewpoints that the press may overlook could change society for the greater good, he argued.

It is hard to look back dispassionately on his 1928 Torches of Freedom march in New York City to get your own by-line on the front page, or to sell more copies of your paper,

or to sell your client’s product or service, many of the same skills are required. With more and more journalists operating as freelances, add on the necessary skill to pitch to an editor and that’s exactly the same ability as PRs need – thick skin and all.

So where does this leave the student of either craft? Unlike journalism, there is a scarcity of PR literature to draw on for prospective students seeking informed opinion (in itself, unlikely) and many students apply with only a vague notion of the course on which they’re embarking. Applicants in interviews sometimes cite influencing public opinion – occasionally for social benefit – although more usually they opt for clients’ commercial gain. But few have any idea how well informed they must be if they are to be effective.

Bernays maintained that in a fractured society – one we might call multicultural today – social causes need publicity, and wrote: “Symbols need to be attached to proposals… to make them less abstract and more marketable. Circumstances need to be created to dramatize their importance and also get the attention of newspapers. The press is vitally important because newspaper coverage can re-translate these pro-social ideas so that

they become fact with [the] power to influence large bodies of people.”

Branded “the assassin of democracy” and vilified for manipulating the press, Bernays’s reputation, along with other publicists in the first half of the last century, took a direct hit after the Second World War. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter is said to have described Bernays as a “professional poisoner of the public mind, exploiter of foolishness, fanaticism and self-interest”.

His brand of public persuasion was seen as the inspiration for Nazi propaganda, and Bernays himself, acceding to this ruinous post-war view, said that effective propaganda must have, at its core, the truth: “But, it is more than that. It is also about shaping or creating events to demonstrate that truth.”

A veneer of respectability

But PR’s ability to change perception, presaged by Bernays, is now commonplace: Unilever’s resoundingly successful commercial Dove soap “Campaign for Real Beauty” and, in social marketing – with society as the beneficiary rather than the initiating organisation – anti-smoking, contraception, AIDs, and drink-driving campaigns, among countless others, give PR a veneer of social respectability. Interestingly, it is in some editorial suites that the last bastions stand, and public relations is still verboten.

Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre famously never lunches with PRs, although some of those operating on his behalf beyond his door occasionally do, even if holding their noses. Nevertheless reporters need data and contacts and publicists need reporters. It works both ways. A widespread modus operandi exists among professionals based on a shared understanding of the omnipresent pressure of an insatiable 24-hour media market. Given their proximity, the consequent growth in free movement between the two disciplines is hardly surprising.

With luck and time, the workplace reality will be reflected in higher education, particularly in journalism schools, where students facing an uncertain future could benefit from greater appreciation and integration. In its latest employment survey (March this year) recruitment specialists Reed.co.uk’s figures show that demand for those working in marketing and PR bucks the general trend and continues to rise; a glimmer of hope in an otherwise adverse story. CBI figures corroborate the finding, showing a continuing steady rise in these sectors. As professional purveyors of information, it is surely good news for those on both sides of the ancient divide that part of the market is buoyant, offering jobs for both prospective

journalism and public relations practitioners.

Trish Evans is a former journalist and PR strategist who runs the BA Public

Relations degree course at the University of Westminster, London.

Posted by British Journalism Review @ 4.02am on 5 June, 2010

Tony Bennett- Investigator

- Posts : 16926

Activity : 24792

Likes received : 3749

Join date : 2009-11-25

Age : 77

Location : Shropshire

Similar topics

Similar topics» Pat Brown: TEN MISSING AND MURDERED CHILDREN'S CASES THAT HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH MADELEINE MCCANN

» Are police any closer to finding Madeleine? Watch Oxygen's Madeleine McCann: 10 Years Later on Sat., Nov. 4

» Suranne Jones will play the mother of an abducted ten-year-old girl in a stage drama with chilling similarities to the Madeleine McCann and Milly Dowler cases.

» Rate My Teachers: Philomena McCann, Ullapool - not many of the McCann clan left with a decent reputation, having disposed of Madeleine Beth McCann's corpse somewhere

» Historical crimes – like the 2007 disappearance of Maddie McCann - will be put on hold as police prioritise cases where there is a 'critical' need to investigate.

» Are police any closer to finding Madeleine? Watch Oxygen's Madeleine McCann: 10 Years Later on Sat., Nov. 4

» Suranne Jones will play the mother of an abducted ten-year-old girl in a stage drama with chilling similarities to the Madeleine McCann and Milly Dowler cases.

» Rate My Teachers: Philomena McCann, Ullapool - not many of the McCann clan left with a decent reputation, having disposed of Madeleine Beth McCann's corpse somewhere

» Historical crimes – like the 2007 disappearance of Maddie McCann - will be put on hold as police prioritise cases where there is a 'critical' need to investigate.

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum