Dr Con Man

Page 1 of 1 • Share

Dr Con Man

Dr Con Man

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/sep/01/paolo-macchiarini-scientist-surgeon-rise-and-fall

'Macchiarini’s deceit was so outlandish, Vanity Fair sought the opinion of the Harvard professor Ronald Schouten, an expert on psychopaths, who gave this diagnosis-at-a-distance: “Macchiarini is the extreme form of a con man. He’s clearly bright and has accomplishments, but he can’t contain himself. There’s a void in his personality that he seems to want to fill by conning more and more people.”'

'Macchiarini’s deceit was so outlandish, Vanity Fair sought the opinion of the Harvard professor Ronald Schouten, an expert on psychopaths, who gave this diagnosis-at-a-distance: “Macchiarini is the extreme form of a con man. He’s clearly bright and has accomplishments, but he can’t contain himself. There’s a void in his personality that he seems to want to fill by conning more and more people.”'

roy rovers- Posts : 473

Activity : 538

Likes received : 51

Join date : 2012-03-04

Re: Dr Con Man

Re: Dr Con Man

Don't forget this bit Mr Rovers:

"Which left a big, burning question in the air: if Macchiarini was a pathological liar in matters of love, what about his medical research? Was he conning his patients, his colleagues and the scientific community?"

And...

"If there is a moral to this tale, it’s that we need to be wary of medical messiahs with their promises of salvation."

Or pathological liars that tell tall tales of abduction for that matter

"Which left a big, burning question in the air: if Macchiarini was a pathological liar in matters of love, what about his medical research? Was he conning his patients, his colleagues and the scientific community?"

And...

"If there is a moral to this tale, it’s that we need to be wary of medical messiahs with their promises of salvation."

Or pathological liars that tell tall tales of abduction for that matter

____________________

PeterMac's FREE e-book

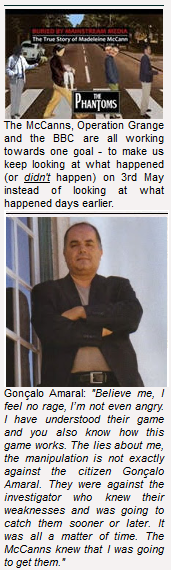

Gonçalo Amaral: The truth of the lie

CMOMM & MMRG Blog

MAGA

MAGA

MBGA

MBGA

A wise man once said:

"Be careful who you let on to your ship,

because some people will sink the whole ship

just because they can't be the Captain."

Re: Dr Con Man

Re: Dr Con Man

I watched the expose documentary which followed some of Macchiarini's operations last year. He came across as extemely charismatic but extremely dangerous.

Part of the programme followed a young mother who'd had a serious car accident which resulted in partial wind pipe removal and a permanent tracheostomy (hole in neck to enable breathing and speech). She was leading a reasonably normal life. Macchiarini constantly reassured the frightened woman that everything would be fine. It wasn't. She died soon after the operation when the grafted wind pipe failed.

During the programme, I can't remember if it was with the above patient or not, Macchiarini was scheduled to perform a high profile transplant. Several wind pipes had been grown but a day before the operation it was drawn to Macchiarini's attention, on camera, that none were of good enough quality to safely proceed. A doctor in his team asked for his opinion and with apparently little consideration he is seen deciding on the best of the samples and basically saying, 'that one will do'. It had already been stated that it wasn't either thick enough or long enough. The patient died soon after the procedure.

Human life seems cheap to this man. If he was at all suitable to be a doctor of any sort (never mind a surgeon) he would have stopped himself after the first death/failure. He came across as an egotist and someone who soaked up the adulation. He continues to refuse to accept that he has done anything wrong.

Even when his patients were consistently dropping dead no one stopped him. He had an answer for everything/everyone. His confidence and arrogance never waivered and he had many high profile friends. Remarkably this resulted in him carrying on doing what he was doing despite the constant failures.

The following extract from The Guardian article sums up the importance of friends in high places (until, that is, public pressure becomes just too strong):

With Macchiarini’s exploits endorsed by management and breathlessly reported in the media, it was all too easy to jump on that bandwagon.

And difficult to jump off. In early 2014, four Karolinska doctors defied the reigning culture of silence by complaining about Macchiarini. In their view, he was grossly misrepresenting his results and the health of his patients. An independent investigator agreed. But the vice-chancellor of Karolinska Institute, Anders Hamsten, wasn’t bound by this judgement. He officially cleared Macchiarini of scientific misconduct, allowing merely that he’d sometimes acted “without due care”.

For their efforts, the whistleblowers were punished. When Macchiarini accused one of them, Karl-Henrik Grinnemo, of stealing his work in a grant application, Hamsten found him guilty. As Grinnemo recalls, it nearly destroyed his career: “I didn’t receive any new grants. No one wanted to collaborate with me. We were doing good research, but it didn’t matter … I thought I was going to lose my lab, my staff – everything.”

This went on for three years until, just recently, Grinnemo was cleared of all wrongdoing.

The Macchiarini scandal claimed many of his powerful friends. The vice-chancellor, Anders Hamsten, resigned. So did Karolinska’s dean of research. Likewise the secretary-general of the Nobel Committee. The university board was dismissed and even Harriet Wallberg, who’d moved on to become the chancellor for all Swedish universities, lost her job.

Part of the programme followed a young mother who'd had a serious car accident which resulted in partial wind pipe removal and a permanent tracheostomy (hole in neck to enable breathing and speech). She was leading a reasonably normal life. Macchiarini constantly reassured the frightened woman that everything would be fine. It wasn't. She died soon after the operation when the grafted wind pipe failed.

During the programme, I can't remember if it was with the above patient or not, Macchiarini was scheduled to perform a high profile transplant. Several wind pipes had been grown but a day before the operation it was drawn to Macchiarini's attention, on camera, that none were of good enough quality to safely proceed. A doctor in his team asked for his opinion and with apparently little consideration he is seen deciding on the best of the samples and basically saying, 'that one will do'. It had already been stated that it wasn't either thick enough or long enough. The patient died soon after the procedure.

Human life seems cheap to this man. If he was at all suitable to be a doctor of any sort (never mind a surgeon) he would have stopped himself after the first death/failure. He came across as an egotist and someone who soaked up the adulation. He continues to refuse to accept that he has done anything wrong.

Even when his patients were consistently dropping dead no one stopped him. He had an answer for everything/everyone. His confidence and arrogance never waivered and he had many high profile friends. Remarkably this resulted in him carrying on doing what he was doing despite the constant failures.

The following extract from The Guardian article sums up the importance of friends in high places (until, that is, public pressure becomes just too strong):

With Macchiarini’s exploits endorsed by management and breathlessly reported in the media, it was all too easy to jump on that bandwagon.

And difficult to jump off. In early 2014, four Karolinska doctors defied the reigning culture of silence by complaining about Macchiarini. In their view, he was grossly misrepresenting his results and the health of his patients. An independent investigator agreed. But the vice-chancellor of Karolinska Institute, Anders Hamsten, wasn’t bound by this judgement. He officially cleared Macchiarini of scientific misconduct, allowing merely that he’d sometimes acted “without due care”.

For their efforts, the whistleblowers were punished. When Macchiarini accused one of them, Karl-Henrik Grinnemo, of stealing his work in a grant application, Hamsten found him guilty. As Grinnemo recalls, it nearly destroyed his career: “I didn’t receive any new grants. No one wanted to collaborate with me. We were doing good research, but it didn’t matter … I thought I was going to lose my lab, my staff – everything.”

This went on for three years until, just recently, Grinnemo was cleared of all wrongdoing.

The Macchiarini scandal claimed many of his powerful friends. The vice-chancellor, Anders Hamsten, resigned. So did Karolinska’s dean of research. Likewise the secretary-general of the Nobel Committee. The university board was dismissed and even Harriet Wallberg, who’d moved on to become the chancellor for all Swedish universities, lost her job.

skyrocket- Posts : 755

Activity : 1537

Likes received : 732

Join date : 2015-06-18

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum