Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present

The Complete Mystery of Madeleine McCann™ :: Professional and Featured blogs :: Featured professional blogs

Page 1 of 1 • Share

Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present

Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present

Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present

Popular newspapers in Britain are commonly criticised for providing unsophisticated, distasteful and intrusive journalism, driven by an aggressive pursuit of exclusives and an unscrupulous desire for profit. The revelation that the News of the World hacked the phones of individuals including murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler (a revelation that prompting the closure of the newspaper in July 2011) is an example which helps to explain why attitudes towards tabloids are often so negative. As journalist Jonathan Freedland commented, coverage of the incident painted a picture of a popular press that had ‘slipped out of the gutter and into the sewer’.

In Adrian Bingham and Martin Conboy’s lively and impressive new book plenty of evidence is provided to illustrate the crude focus upon sensation and scandal that has often characterised the popular press since the 1896 launch of Britain’s first morning daily newspaper aimed at the mass market: Alfred Harmsworth’s Daily Mail. However, setting out to explore broad patterns of continuity and change in popular newspapers over the last century, Bingham and Conboy caution against the drawing of simplistic and stereotypically negative conclusions about the role of the press by referring to the wide range of material that the tabloids contained. Indeed, we are told in the introduction that evidence will be provided of ‘when tabloids were progressive and generous, when they provided a powerful voice for ordinary people’, suggesting that ‘tabloid culture is more complex and nuanced than many have given it credit for’ .

The reason why the role of the popular press in 20th-century Britain is deserving of serious and sustained scholarly attention is clearly outlined by Bingham and Conboy in the preface. About 85 per cent of the population saw a newspaper everyday by the early 1950s, and the British people read more newspapers per head than any other nation. The popular press was therefore an important, and a highly successful, force in 20th-century British social and political life, shaping how millions of people were informed about, and made sense of, the world around them. Tabloid Century is concerned with how the popular press represented key public events, institutions and people in addition to how personal and social identities were portrayed. The book is organized into six main chapters, which examine each of the following themes in turn: war; politics; monarchy and celebrity; gender and sexuality; class; and race and nation.

The main source base for Tabloid Century is the content of the market-leading national daily newspapers, such as the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, the Daily Express and the Sun. This methodological approach represents a clear shift away from many more traditional press histories, which ‘focus on the production of newspapers – on the owners, editors, reporters and printers who wrote, packaged or paid for the news – rather than on their content’ (p. vii). Motivated by the ‘cultural turn’, and the acknowledgement that socio-political identities are often linguistic constructions, Tabloid Century is part of an emerging wave of scholarship that has started to place much greater value upon the language and content of popular newspapers as historical source material. The feasibility of this approach has been aided by the digitisation of vast numbers of newspapers in recent years. Although key works in the field are referenced throughout, Bingham and Conboy do not extensively examine these methodological and historiographical developments in Tabloid Century. This is partly because one of the authors’ stated aims was to produce an accessible text that adopts a tone mid-way between the colourful Fleet Street memoirs that they engage with and the more dense academic literature. Furthermore, as the Directors of the Centre for the Study of Journalism and History at the University of Sheffield, Bingham and Conboy’s previous work has already extensively and authoritatively contributed to, and provided commentary on, the more recent approach to historical newspapers that places language and content at the centre of the analysis.

The introduction to Tabloid Century provides a useful context for helping readers to understand the 20th-century development of the ‘tabloid model’. Bingham and Conboy identify three key waves of editorial innovation embraced by newspapers that took on the tabloid characteristics of populism, accessibility and brevity. First, Alfred Harmsworth’s launch of the Daily Mail at the turn of the 20th century, and his application of populist techniques previously used in Sunday newspapers and the American press, heralded the start of the tabloid century. The newspaper soon secured a circulation of a million copies a day. A flourishing popular daily newspaper market developed as the Mail’s successful formula, incorporating gossip columns and human-interest stories, was copied by titles including the Daily Express (launched in 1900). The second wave of editorial innovation during the 1930s started with the relaunch of the left-wing Daily Herald – the newspaper finally embraced human-interest and dramatically increased its use of photographs and advertising. Unlike the Mail and its competitors, which had originally targeted the lower middle classes, the Herald was aimed directly at the unionised working classes. By 1933 the Herald’s increased accessibility had clearly paid off; it became the first newspaper to sell two million copies. The 1930s also saw the reinvention of the Daily Mirror – it became the first newspaper to adopt a recognisably tabloid style. Combining colloquialism, thick black type and bold block headlines with the pursuit of greater sensation, the Mirror’s circulation steadily rose and became Britain’s most popular newspaper in 1949. The final wave of editorial innovation took place in the 1970s, heralded by the 1969 relaunch of the Sun, under the ownership of Rupert Murdoch. In addition to providing sensational celebrity stories, the newspaper included photographs of topless female models, signalling a more brazen treatment of sex. By 1978 the Sun was the nation’s bestselling newspaper, briefly reaching a circulation of four million, and inspiring the launch of a less successful imitation in the Daily Star.

Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of politics and tabloid journalism clearly highlights the need for caution when relying upon simplistic and stereotypically negative preconceptions about the popular press. Popular political journalism was often crude and reductive, and Conservative opinions, rather than voices that challenged the status quo, frequently dominated. But the popular press also launched crusades about issues deemed to directly impact upon the lives of readers – such as living standards and education – and, at times, presented strong political views in a bright and accessible language. Bingham and Conboy identify four broad periods when the press’s balance of political party support altered significantly. The first period, up to the 1930s, saw the market dominated by right-wing newspapers, such as the Mail and the Express. From the 1930s, with the relaunch of the Daily Herald and the reinvention of the Mirror, left-of-centre opinions became more prominent, aiding mid-century reform and reconstruction. The 1970s ushered in the third period. Murdoch’s Sun led a shift to the right, and the press played a significant role in the success of Margaret Thatcher’s administration. Finally, Tony Blair’s wooing of the newspapers and his bid to tone down the left-wing elements of the Labour Party during the 1990s led the press to adopt a more centrist position. This stance first benefitted Blair – with the press adopting front-page headlines such as ‘Blair Kicks Out Lefties’ (p. 91) – and went on to benefit David Cameron’s Conservatives. This tabloid cynicism about the left is also explored in Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of class. From the 1980s the press increasingly indulged public interest in the glamorous lifestyles of celebrities, while simultaneously attacking those identified as ‘welfare scroungers’. This encouraged an individualist culture where collectivism was presented as both outdated and worrying. The newspapers engaged both with readers’ aspirations, and with their concerns about the perils of an interfering state.

It is always difficult for historians to measure the actual impact of newspaper content upon readers who could ignore, resist or misunderstand material aiming, for example, to influence their political views. However, Bingham and Conboy convincingly argue that massive circulation figures make it hard to deny the newspapers’ significance in terms of subtly framing issues, helping to set agendas for debate, and enabling certain people and institutions to dominate discussion. The fact that central political figures such as Thatcher, Blair and Cameron worked hard to gain the support of the newspapers shows that they certainly believed in the power of the popular press to influence large sections of public opinion.

In their discussion of war and the popular press, Bingham and Conboy again caution against the drawing of simplistic conclusions – namely, that tabloids always provided jingoistic, uncritical reportage of conflict. During the total wars of the first half of the 20th century, the press did play a key role in the mobilisation of the nation, sustaining morale and uniting readers, especially following the introduction of the Ministry of information and increasing censorship. Nevertheless, reportage of some of the more remote wars of later years suggests a more complex picture. Criticism of engagements in the Middle East understandably grew in the popular press as military operations dragged on and became increasingly costly. However, the Mirror, under the editorship of Piers Morgan, opposed British involvement in the Iraq War from the beginning in 2003. The Mirror’s ‘No War’ slogan was projected onto the Houses of Parliament and the newspaper heavily supported the anti-war protests in London.

A balanced approach to the source material is again taken in the discussion of gender and sexuality in the press. When Harmsworth launched the Mail in 1896 he reached out to previously neglected female readers by providing material on fashion, housewifery and motherhood. However, in the decade after the First World War, the popular press provided a wide range of representations of women that extended far beyond domesticity. The Mail encouraged great interest in the activities of ‘flappers’, and the press provided reports of women as first-time voters, entering public and professional roles, dancing, smoking and driving. However, representations of women in the press were increasingly sexualised by the middle decades of the century, especially when female ‘pin-ups’ were introduced as a form of titillation for men. The topless ‘Page 3 girl’ became a regular feature in the Sun from 1970 – this was at a time when the women’s movement was starting to pay closer attention to media sexism and crude gender stereotyping. The male dominance of newsrooms was also scrutinised, and by the end of the century some talented women, such as Rebekah Brooks, had risen to positions of editorial authority. Nevertheless, much remains unchanged and tabloids still seek to appeal to women primarily through lifestyle and celebrity journalism. With regard to sexuality, there was an expectation that tabloid readers were heterosexual and alternative sexualities were marginalised or ridiculed by the newspapers for much of the 20th century. The tabloid reportage of the emergence of HIV/AIDS in the early 1980s underlined remaining prejudices, although during the 1990s and 2000s greater tolerance slowly emerged.

The theme of change features heavily in Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of monarchy and celebrity. Press representations and human-interest discussions of public figures are examined to help consider the changing boundaries of public and private. Pride, patriotism and deference marked the popular press’s coverage of the monarchy from 1897, (when the Mail enthusiastically reported upon the celebrations of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee), up to the Second World War. Particularly from the late 1970s, however, there was a growing willingness, especially by Murdoch’s Sun, to expose members of the royal family to the same level of scrutiny as celebrities. This press intrusiveness was symbolised by the excessive pursuit of Princess Diana. Diana’s charm and beauty made her irresistible to the newspapers, which also circulated stories of affairs, arguments with Prince Charles and suicide attempts. The press’s pursuit of other public figures was also characterised by increasing intrusiveness into their private lives – the ‘kiss-and-tell’ story developed into a central ingredient of the tabloid model during the 1980s. The foundation of the Press Complaints Commission in 1990 did little to curb the newspapers’ competitive instincts. Private detectives were paid to investigate stories and phone hacking was widespread by the late 1990s.

The theme of striking continuity dominates Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of race and nation. The number of black and Asian journalists working on the mainstream press slowly increased into the 21st century. Yet very few held positions of editorial authority, serving to underline the white metropolitan English outlook of the tabloids. Tabloids have continuously used the language of race and nation to unite diverse mass readerships that cross boundaries of class, gender and age. In the second half of the century racialised and derogatory language did become increasingly less acceptable. The Sun was praised by the Commission for Racial Equality for its reportage of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 – the newspaper had sought to emphasise that Al-Qaeda did not represent Islam. However, beneath the surface, the stereotyping of immigrants as threatening ‘outsiders’ has been continuous. When 120,000 Jews entered Britain between 1880 and 1914 the press provided fierce warnings about the ‘intolerable nuisance’ that these ‘aliens’ who ‘naturally have no British patriotism’ posed to the British way of life (p. 204). In a similarly sensationalist style, in 2003 the Express provided 22 front-page stories about asylum-seekers and refugees over a period of 31 days, printing headlines such as ‘Asylum War Criminals on Our Streets’, and ‘Asylum: Tidal Wave of Crime’.

Throughout Tabloid Century important consideration is given to very recent press controversies and trends. Newspaper circulation figures have been declining since the final decades of the 20th century, and have continued to fall sharply in the 21st century. However, Bingham and Conboy convincingly argue that this fall reflects the success, rather than the failure, of the tabloid model. Other media forms, namely broadcasting, magazines and the internet, have embraced tabloid elements of speed, brevity, accessibility and controversy. The reduction of the boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture has also led to the populist priorities of the tabloids to being taken up by a wide range of media forms. This so-called ‘tabloidisation’ of the media has made it more difficult for the newspapers to find distinctive stories and retain loyal readers. Strategies such as the hacking of phones stemmed from the pressure that the tabloids faced to obtain exclusives and to keep ahead of the competition. Yet, paradoxically, it is also this cut-throat journalism that has served to severely damage the standing of the tabloids, causing reader trust ratings to fall and contributing to their decline in power and influence.

Overall, the key strength of this ambitious and engaging new book is the authors’ ability to skilfully trace patterns and changes in press representations of British society throughout this period of over 100 years. This was undoubtedly a huge undertaking considering the sheer volume of source material available to sift through and analyse, with six editions of the daily newspapers produced each week. Bingham and Conboy acknowledge that the drawback of providing such breadth in a single book is that much material is left out or passed over rapidly, with some important newspaper content, such as sport and crime reportage, receiving only limited attention. Nevertheless, the much-needed overview provided in Tabloid Century stimulates interest and encourages a more thoughtful and less dismissive approach towards the tabloid press as source material for historians. Tabloid Century is vital reading for scholars and general readers interested in how the popular press shaped, and was shaped by, 20th-century British social and political life, and for those interested in where the tabloid press that we have today came from.

https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/1825

Popular newspapers in Britain are commonly criticised for providing unsophisticated, distasteful and intrusive journalism, driven by an aggressive pursuit of exclusives and an unscrupulous desire for profit. The revelation that the News of the World hacked the phones of individuals including murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler (a revelation that prompting the closure of the newspaper in July 2011) is an example which helps to explain why attitudes towards tabloids are often so negative. As journalist Jonathan Freedland commented, coverage of the incident painted a picture of a popular press that had ‘slipped out of the gutter and into the sewer’.

In Adrian Bingham and Martin Conboy’s lively and impressive new book plenty of evidence is provided to illustrate the crude focus upon sensation and scandal that has often characterised the popular press since the 1896 launch of Britain’s first morning daily newspaper aimed at the mass market: Alfred Harmsworth’s Daily Mail. However, setting out to explore broad patterns of continuity and change in popular newspapers over the last century, Bingham and Conboy caution against the drawing of simplistic and stereotypically negative conclusions about the role of the press by referring to the wide range of material that the tabloids contained. Indeed, we are told in the introduction that evidence will be provided of ‘when tabloids were progressive and generous, when they provided a powerful voice for ordinary people’, suggesting that ‘tabloid culture is more complex and nuanced than many have given it credit for’ .

The reason why the role of the popular press in 20th-century Britain is deserving of serious and sustained scholarly attention is clearly outlined by Bingham and Conboy in the preface. About 85 per cent of the population saw a newspaper everyday by the early 1950s, and the British people read more newspapers per head than any other nation. The popular press was therefore an important, and a highly successful, force in 20th-century British social and political life, shaping how millions of people were informed about, and made sense of, the world around them. Tabloid Century is concerned with how the popular press represented key public events, institutions and people in addition to how personal and social identities were portrayed. The book is organized into six main chapters, which examine each of the following themes in turn: war; politics; monarchy and celebrity; gender and sexuality; class; and race and nation.

The main source base for Tabloid Century is the content of the market-leading national daily newspapers, such as the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, the Daily Express and the Sun. This methodological approach represents a clear shift away from many more traditional press histories, which ‘focus on the production of newspapers – on the owners, editors, reporters and printers who wrote, packaged or paid for the news – rather than on their content’ (p. vii). Motivated by the ‘cultural turn’, and the acknowledgement that socio-political identities are often linguistic constructions, Tabloid Century is part of an emerging wave of scholarship that has started to place much greater value upon the language and content of popular newspapers as historical source material. The feasibility of this approach has been aided by the digitisation of vast numbers of newspapers in recent years. Although key works in the field are referenced throughout, Bingham and Conboy do not extensively examine these methodological and historiographical developments in Tabloid Century. This is partly because one of the authors’ stated aims was to produce an accessible text that adopts a tone mid-way between the colourful Fleet Street memoirs that they engage with and the more dense academic literature. Furthermore, as the Directors of the Centre for the Study of Journalism and History at the University of Sheffield, Bingham and Conboy’s previous work has already extensively and authoritatively contributed to, and provided commentary on, the more recent approach to historical newspapers that places language and content at the centre of the analysis.

The introduction to Tabloid Century provides a useful context for helping readers to understand the 20th-century development of the ‘tabloid model’. Bingham and Conboy identify three key waves of editorial innovation embraced by newspapers that took on the tabloid characteristics of populism, accessibility and brevity. First, Alfred Harmsworth’s launch of the Daily Mail at the turn of the 20th century, and his application of populist techniques previously used in Sunday newspapers and the American press, heralded the start of the tabloid century. The newspaper soon secured a circulation of a million copies a day. A flourishing popular daily newspaper market developed as the Mail’s successful formula, incorporating gossip columns and human-interest stories, was copied by titles including the Daily Express (launched in 1900). The second wave of editorial innovation during the 1930s started with the relaunch of the left-wing Daily Herald – the newspaper finally embraced human-interest and dramatically increased its use of photographs and advertising. Unlike the Mail and its competitors, which had originally targeted the lower middle classes, the Herald was aimed directly at the unionised working classes. By 1933 the Herald’s increased accessibility had clearly paid off; it became the first newspaper to sell two million copies. The 1930s also saw the reinvention of the Daily Mirror – it became the first newspaper to adopt a recognisably tabloid style. Combining colloquialism, thick black type and bold block headlines with the pursuit of greater sensation, the Mirror’s circulation steadily rose and became Britain’s most popular newspaper in 1949. The final wave of editorial innovation took place in the 1970s, heralded by the 1969 relaunch of the Sun, under the ownership of Rupert Murdoch. In addition to providing sensational celebrity stories, the newspaper included photographs of topless female models, signalling a more brazen treatment of sex. By 1978 the Sun was the nation’s bestselling newspaper, briefly reaching a circulation of four million, and inspiring the launch of a less successful imitation in the Daily Star.

Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of politics and tabloid journalism clearly highlights the need for caution when relying upon simplistic and stereotypically negative preconceptions about the popular press. Popular political journalism was often crude and reductive, and Conservative opinions, rather than voices that challenged the status quo, frequently dominated. But the popular press also launched crusades about issues deemed to directly impact upon the lives of readers – such as living standards and education – and, at times, presented strong political views in a bright and accessible language. Bingham and Conboy identify four broad periods when the press’s balance of political party support altered significantly. The first period, up to the 1930s, saw the market dominated by right-wing newspapers, such as the Mail and the Express. From the 1930s, with the relaunch of the Daily Herald and the reinvention of the Mirror, left-of-centre opinions became more prominent, aiding mid-century reform and reconstruction. The 1970s ushered in the third period. Murdoch’s Sun led a shift to the right, and the press played a significant role in the success of Margaret Thatcher’s administration. Finally, Tony Blair’s wooing of the newspapers and his bid to tone down the left-wing elements of the Labour Party during the 1990s led the press to adopt a more centrist position. This stance first benefitted Blair – with the press adopting front-page headlines such as ‘Blair Kicks Out Lefties’ (p. 91) – and went on to benefit David Cameron’s Conservatives. This tabloid cynicism about the left is also explored in Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of class. From the 1980s the press increasingly indulged public interest in the glamorous lifestyles of celebrities, while simultaneously attacking those identified as ‘welfare scroungers’. This encouraged an individualist culture where collectivism was presented as both outdated and worrying. The newspapers engaged both with readers’ aspirations, and with their concerns about the perils of an interfering state.

It is always difficult for historians to measure the actual impact of newspaper content upon readers who could ignore, resist or misunderstand material aiming, for example, to influence their political views. However, Bingham and Conboy convincingly argue that massive circulation figures make it hard to deny the newspapers’ significance in terms of subtly framing issues, helping to set agendas for debate, and enabling certain people and institutions to dominate discussion. The fact that central political figures such as Thatcher, Blair and Cameron worked hard to gain the support of the newspapers shows that they certainly believed in the power of the popular press to influence large sections of public opinion.

In their discussion of war and the popular press, Bingham and Conboy again caution against the drawing of simplistic conclusions – namely, that tabloids always provided jingoistic, uncritical reportage of conflict. During the total wars of the first half of the 20th century, the press did play a key role in the mobilisation of the nation, sustaining morale and uniting readers, especially following the introduction of the Ministry of information and increasing censorship. Nevertheless, reportage of some of the more remote wars of later years suggests a more complex picture. Criticism of engagements in the Middle East understandably grew in the popular press as military operations dragged on and became increasingly costly. However, the Mirror, under the editorship of Piers Morgan, opposed British involvement in the Iraq War from the beginning in 2003. The Mirror’s ‘No War’ slogan was projected onto the Houses of Parliament and the newspaper heavily supported the anti-war protests in London.

A balanced approach to the source material is again taken in the discussion of gender and sexuality in the press. When Harmsworth launched the Mail in 1896 he reached out to previously neglected female readers by providing material on fashion, housewifery and motherhood. However, in the decade after the First World War, the popular press provided a wide range of representations of women that extended far beyond domesticity. The Mail encouraged great interest in the activities of ‘flappers’, and the press provided reports of women as first-time voters, entering public and professional roles, dancing, smoking and driving. However, representations of women in the press were increasingly sexualised by the middle decades of the century, especially when female ‘pin-ups’ were introduced as a form of titillation for men. The topless ‘Page 3 girl’ became a regular feature in the Sun from 1970 – this was at a time when the women’s movement was starting to pay closer attention to media sexism and crude gender stereotyping. The male dominance of newsrooms was also scrutinised, and by the end of the century some talented women, such as Rebekah Brooks, had risen to positions of editorial authority. Nevertheless, much remains unchanged and tabloids still seek to appeal to women primarily through lifestyle and celebrity journalism. With regard to sexuality, there was an expectation that tabloid readers were heterosexual and alternative sexualities were marginalised or ridiculed by the newspapers for much of the 20th century. The tabloid reportage of the emergence of HIV/AIDS in the early 1980s underlined remaining prejudices, although during the 1990s and 2000s greater tolerance slowly emerged.

The theme of change features heavily in Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of monarchy and celebrity. Press representations and human-interest discussions of public figures are examined to help consider the changing boundaries of public and private. Pride, patriotism and deference marked the popular press’s coverage of the monarchy from 1897, (when the Mail enthusiastically reported upon the celebrations of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee), up to the Second World War. Particularly from the late 1970s, however, there was a growing willingness, especially by Murdoch’s Sun, to expose members of the royal family to the same level of scrutiny as celebrities. This press intrusiveness was symbolised by the excessive pursuit of Princess Diana. Diana’s charm and beauty made her irresistible to the newspapers, which also circulated stories of affairs, arguments with Prince Charles and suicide attempts. The press’s pursuit of other public figures was also characterised by increasing intrusiveness into their private lives – the ‘kiss-and-tell’ story developed into a central ingredient of the tabloid model during the 1980s. The foundation of the Press Complaints Commission in 1990 did little to curb the newspapers’ competitive instincts. Private detectives were paid to investigate stories and phone hacking was widespread by the late 1990s.

The theme of striking continuity dominates Bingham and Conboy’s discussion of race and nation. The number of black and Asian journalists working on the mainstream press slowly increased into the 21st century. Yet very few held positions of editorial authority, serving to underline the white metropolitan English outlook of the tabloids. Tabloids have continuously used the language of race and nation to unite diverse mass readerships that cross boundaries of class, gender and age. In the second half of the century racialised and derogatory language did become increasingly less acceptable. The Sun was praised by the Commission for Racial Equality for its reportage of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 – the newspaper had sought to emphasise that Al-Qaeda did not represent Islam. However, beneath the surface, the stereotyping of immigrants as threatening ‘outsiders’ has been continuous. When 120,000 Jews entered Britain between 1880 and 1914 the press provided fierce warnings about the ‘intolerable nuisance’ that these ‘aliens’ who ‘naturally have no British patriotism’ posed to the British way of life (p. 204). In a similarly sensationalist style, in 2003 the Express provided 22 front-page stories about asylum-seekers and refugees over a period of 31 days, printing headlines such as ‘Asylum War Criminals on Our Streets’, and ‘Asylum: Tidal Wave of Crime’.

Throughout Tabloid Century important consideration is given to very recent press controversies and trends. Newspaper circulation figures have been declining since the final decades of the 20th century, and have continued to fall sharply in the 21st century. However, Bingham and Conboy convincingly argue that this fall reflects the success, rather than the failure, of the tabloid model. Other media forms, namely broadcasting, magazines and the internet, have embraced tabloid elements of speed, brevity, accessibility and controversy. The reduction of the boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture has also led to the populist priorities of the tabloids to being taken up by a wide range of media forms. This so-called ‘tabloidisation’ of the media has made it more difficult for the newspapers to find distinctive stories and retain loyal readers. Strategies such as the hacking of phones stemmed from the pressure that the tabloids faced to obtain exclusives and to keep ahead of the competition. Yet, paradoxically, it is also this cut-throat journalism that has served to severely damage the standing of the tabloids, causing reader trust ratings to fall and contributing to their decline in power and influence.

Overall, the key strength of this ambitious and engaging new book is the authors’ ability to skilfully trace patterns and changes in press representations of British society throughout this period of over 100 years. This was undoubtedly a huge undertaking considering the sheer volume of source material available to sift through and analyse, with six editions of the daily newspapers produced each week. Bingham and Conboy acknowledge that the drawback of providing such breadth in a single book is that much material is left out or passed over rapidly, with some important newspaper content, such as sport and crime reportage, receiving only limited attention. Nevertheless, the much-needed overview provided in Tabloid Century stimulates interest and encourages a more thoughtful and less dismissive approach towards the tabloid press as source material for historians. Tabloid Century is vital reading for scholars and general readers interested in how the popular press shaped, and was shaped by, 20th-century British social and political life, and for those interested in where the tabloid press that we have today came from.

https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/1825

____________________

“ The secret of life is honesty and fair dealing. If you can fake that, you've got it made" - Groucho Marx

Verdi- ex moderator

- Posts : 34684

Activity : 41936

Likes received : 5932

Join date : 2015-02-02

Location : Flossery

Re: Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present

Re: Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present

Private Eye

Fifty years of filth

Hackwatch , Issue 1510

FROM “Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster” to “Up Yours Delors”, the Sun spent the whole of last week revelling in the front-page splashes, scoops and scandals of the past five decades as it celebrated its 50th anniversary. Here are a few that didn’t make the cut…

FROM “Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster” to “Up Yours Delors”, the Sun spent the whole of last week revelling in the front-page splashes, scoops and scandals of the past five decades as it celebrated its 50th anniversary. Here are a few that didn’t make the cut…

April 1974: Four years after the paper begins the tradition of soft porn at the breakfast table, “17-year-old Jerry Hall from Dallas, Texas”, makes her bare-breasted Page 3 debut. “Watch the Sun for more pictures of Jerry,” the paper warns – but the “Sun Super Girl” goes one better 42 years later by marrying the proprietor, Rupert Murdoch!

November 1982: Proving it is the patriotic paper that really backs Our Boys in the Falklands, the Sun fabricates a “world exclusive” interview with the widow of a Victoria Cross recipient killed in action. When war hero Simon Weston declines an interview request three years later, the paper repeats the trick with a cuts-job so exploitative the executive who commissioned it was suspended for a month.

February 1987: The Sun accuses Elton John of holding bondage orgies with rent boys, and then steps up a campaign of vitriol against him in September by claiming he’d had his pet dogs “silenced by a horrific operation”, despite them barking at the photographer sent to take photos of them. The following year the paper admits it was all nonsense, pays him a record £1m in damages, and prints a grovelling front-page apology beneath the headline “SORRY ELTON!”

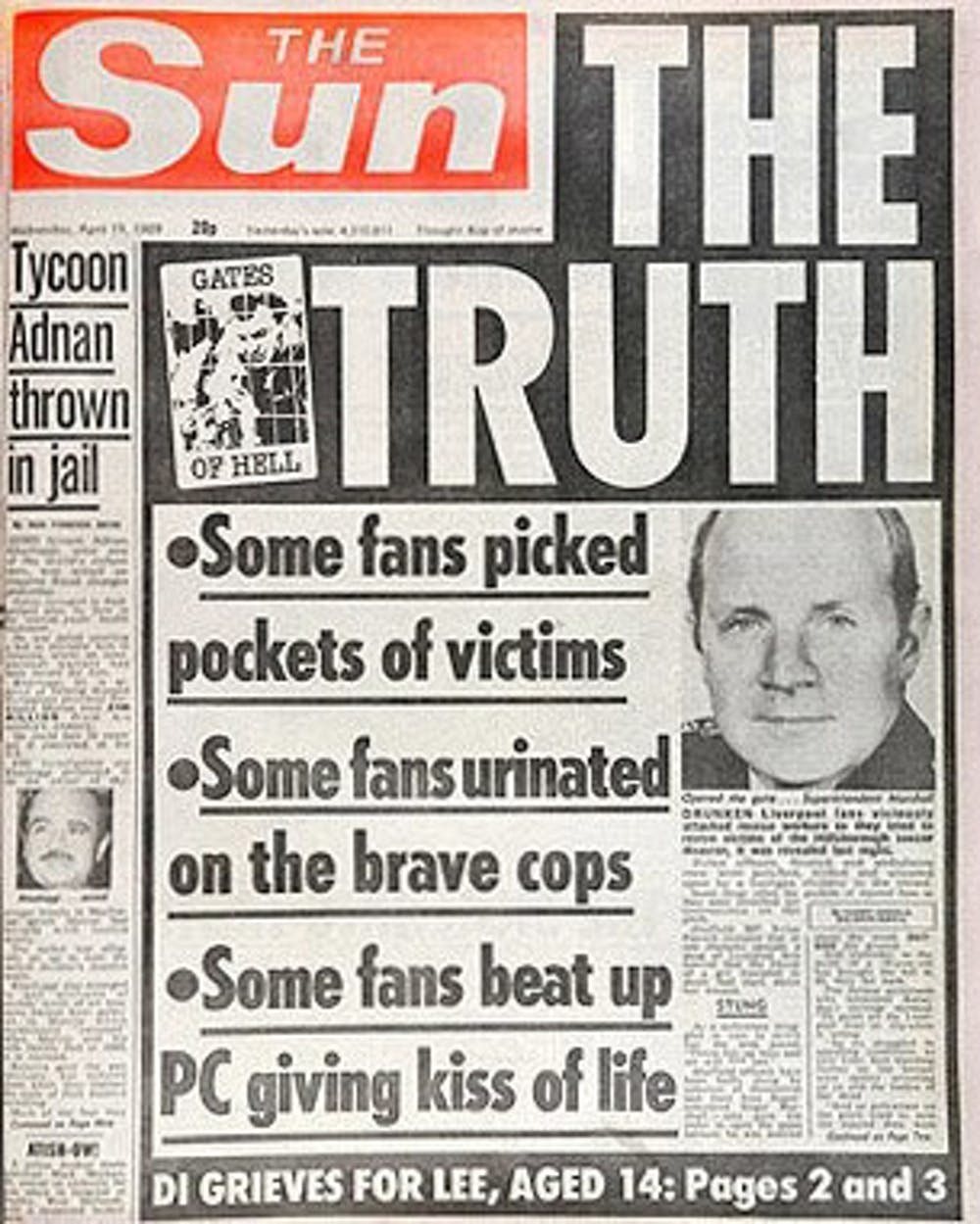

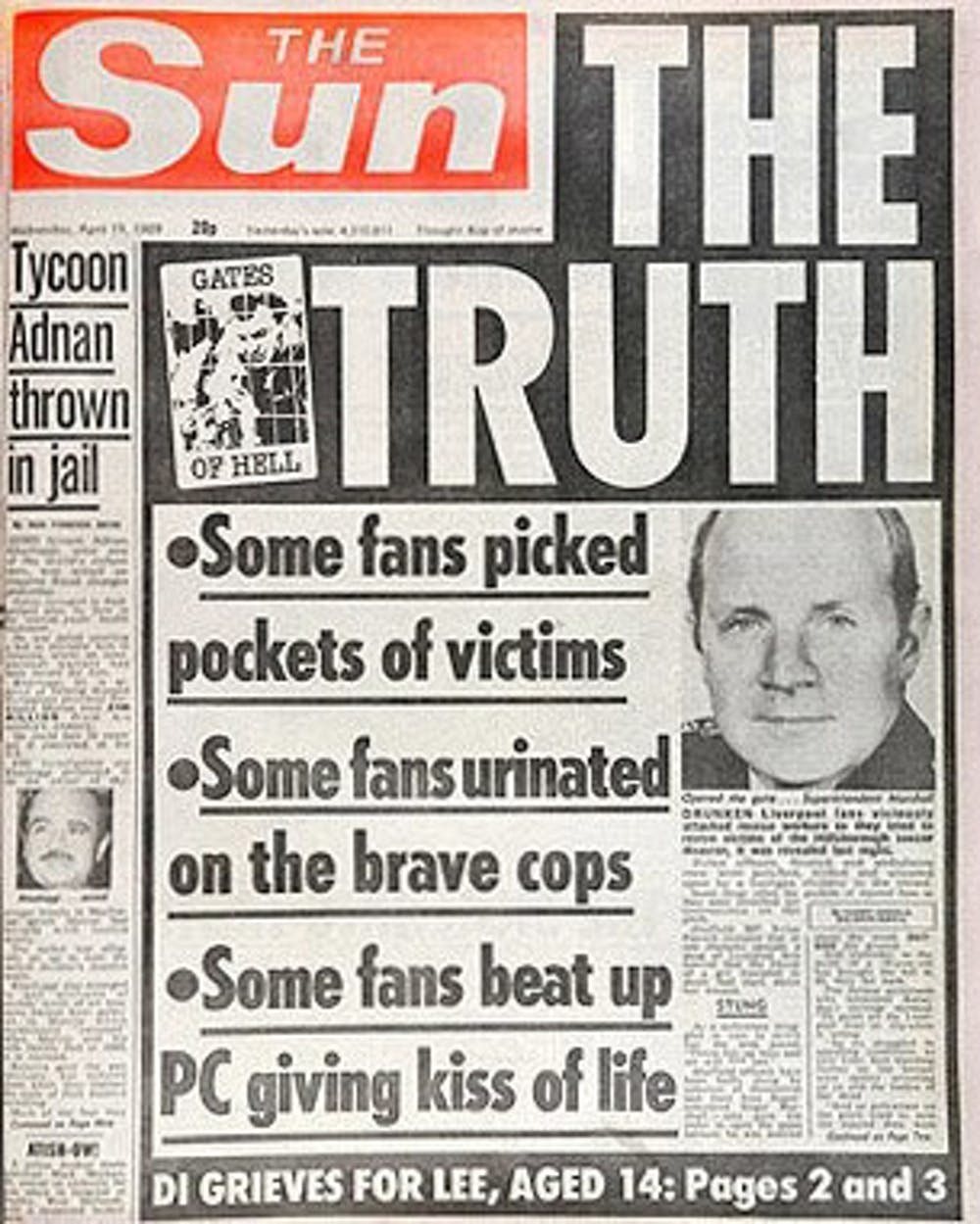

April 1989: A notorious front page prepared by editor Kelvin MacKenzie (above) presents the exact opposite of the truth about the Hillsborough disaster. That November, with HIV diagnoses and deaths both on the rise, the paper prints the equally inaccurate and dangerous claim: “Straight Sex Cannot Give You Aids – Official.”

November 1998: “Sun speaks its mind – TELL US THE TRUTH TONY – Are we being run by a gay mafia?” demands the paper’s front page after several members of Tony Blair’s cabinet are revealed – against their wishes – to be gay. Following outrage, a screeching reverse-ferret: “From now on the Sun will not out homosexuals unless there is major public interest reason to do so,” editor David Yelland promises.

January 2010: News International chief executive Rebekah Brooks hits on a perfect method to dissuade publicist Max Clifford from suing the News of the World over the repeated hacking of his phone: “She got Max to agree £200,000 per annum to represent the Sun/do business with the Sun,” company minutes record. “She could physically turn up with cash to see him.” Clifford, who liked to boast of his ability to keep damaging stories out of the tabloids, is convicted of multiple sex offences four years later.

July 2011: In an attempt to distract attention from the News of the World hacking scandal, management at News International begin grassing up Sun reporters to the police for paying public officials in return for stories. Several journalists are arrested in dawn raids and held on bail for months on end. Two attempt suicide. At least 21 people who gave stories to the Sun, and should have had their identities protected in perpetuity as confidential sources, receive criminal convictions and several of them go to jail. The juries in several trials are told that all payments were encouraged, and authorised by, senior executives at the paper, but that paperwork demonstrating this has mysteriously gone missing. All the journalists are acquitted.

September 2018: After bullishly insisting all the way to the courtroom doors that it would be defending itself against accusations of phone-hacking on the Sun (as opposed to the ones it long since gave up denying on the late News of the World), News Group Newspapers crumbles and settles 15 such cases – but without making any “admission of liability” as regards the still-existing paper.

Fifty years of filth

Hackwatch , Issue 1510

FROM “Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster” to “Up Yours Delors”, the Sun spent the whole of last week revelling in the front-page splashes, scoops and scandals of the past five decades as it celebrated its 50th anniversary. Here are a few that didn’t make the cut…

FROM “Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster” to “Up Yours Delors”, the Sun spent the whole of last week revelling in the front-page splashes, scoops and scandals of the past five decades as it celebrated its 50th anniversary. Here are a few that didn’t make the cut…April 1974: Four years after the paper begins the tradition of soft porn at the breakfast table, “17-year-old Jerry Hall from Dallas, Texas”, makes her bare-breasted Page 3 debut. “Watch the Sun for more pictures of Jerry,” the paper warns – but the “Sun Super Girl” goes one better 42 years later by marrying the proprietor, Rupert Murdoch!

November 1982: Proving it is the patriotic paper that really backs Our Boys in the Falklands, the Sun fabricates a “world exclusive” interview with the widow of a Victoria Cross recipient killed in action. When war hero Simon Weston declines an interview request three years later, the paper repeats the trick with a cuts-job so exploitative the executive who commissioned it was suspended for a month.

February 1987: The Sun accuses Elton John of holding bondage orgies with rent boys, and then steps up a campaign of vitriol against him in September by claiming he’d had his pet dogs “silenced by a horrific operation”, despite them barking at the photographer sent to take photos of them. The following year the paper admits it was all nonsense, pays him a record £1m in damages, and prints a grovelling front-page apology beneath the headline “SORRY ELTON!”

April 1989: A notorious front page prepared by editor Kelvin MacKenzie (above) presents the exact opposite of the truth about the Hillsborough disaster. That November, with HIV diagnoses and deaths both on the rise, the paper prints the equally inaccurate and dangerous claim: “Straight Sex Cannot Give You Aids – Official.”

November 1998: “Sun speaks its mind – TELL US THE TRUTH TONY – Are we being run by a gay mafia?” demands the paper’s front page after several members of Tony Blair’s cabinet are revealed – against their wishes – to be gay. Following outrage, a screeching reverse-ferret: “From now on the Sun will not out homosexuals unless there is major public interest reason to do so,” editor David Yelland promises.

January 2010: News International chief executive Rebekah Brooks hits on a perfect method to dissuade publicist Max Clifford from suing the News of the World over the repeated hacking of his phone: “She got Max to agree £200,000 per annum to represent the Sun/do business with the Sun,” company minutes record. “She could physically turn up with cash to see him.” Clifford, who liked to boast of his ability to keep damaging stories out of the tabloids, is convicted of multiple sex offences four years later.

July 2011: In an attempt to distract attention from the News of the World hacking scandal, management at News International begin grassing up Sun reporters to the police for paying public officials in return for stories. Several journalists are arrested in dawn raids and held on bail for months on end. Two attempt suicide. At least 21 people who gave stories to the Sun, and should have had their identities protected in perpetuity as confidential sources, receive criminal convictions and several of them go to jail. The juries in several trials are told that all payments were encouraged, and authorised by, senior executives at the paper, but that paperwork demonstrating this has mysteriously gone missing. All the journalists are acquitted.

September 2018: After bullishly insisting all the way to the courtroom doors that it would be defending itself against accusations of phone-hacking on the Sun (as opposed to the ones it long since gave up denying on the late News of the World), News Group Newspapers crumbles and settles 15 such cases – but without making any “admission of liability” as regards the still-existing paper.

Similar topics

Similar topics» Scandalized Britain ponders press reform

» Madeleine in Paraguay 2 - This ridiculous story DOES make Britain's mainstream press, after all

» Olive Press: HUNDREDS RUN AGAINST ‘FAKE NEWS’ ON WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY IN MALAGA ON SPAIN’S COSTA DEL SOL

» Joana Morais

» COPS CRACK MADELEINE MCCANN CODES

» Madeleine in Paraguay 2 - This ridiculous story DOES make Britain's mainstream press, after all

» Olive Press: HUNDREDS RUN AGAINST ‘FAKE NEWS’ ON WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY IN MALAGA ON SPAIN’S COSTA DEL SOL

» Joana Morais

» COPS CRACK MADELEINE MCCANN CODES

The Complete Mystery of Madeleine McCann™ :: Professional and Featured blogs :: Featured professional blogs

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum