The Lindbergh kidnapping

Page 1 of 1 • Share

The Lindbergh kidnapping

The Lindbergh kidnapping

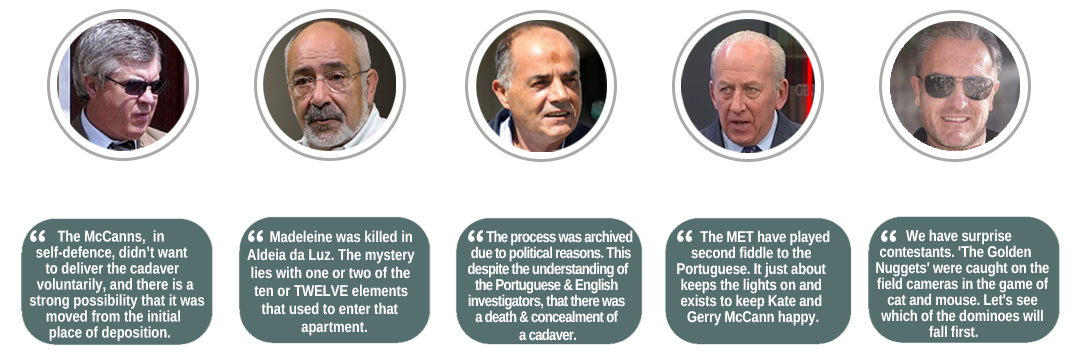

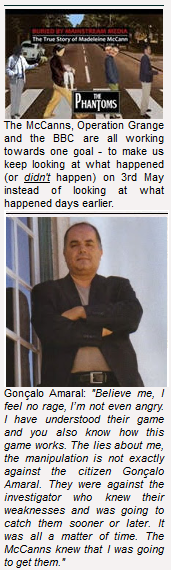

On the Amazon site in respect of the new "Looking for Madeleine" book by Summers and Swan we have this extract:

The 2007 disappearance of a three-year-old Madeleine McCann from her bed in Portugal proved an instant, worldwide sensation. There's been nothing like it since America's Lindbergh kidnapping eighty years ago.

But what is this all about? It actually looks very interesting, and well worth a bit of research.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

The kidnapping of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., the son of famous aviator [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] and [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], was one of the most highly publicized crimes of the 20th century. The 20-month-old toddler was abducted from his family home in [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], on the evening of March 1, 1932.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] Over two months later, on May 12, 1932, his body was discovered a short distance from the Lindberghs' home in neighboring [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.].[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] A medical examination determined that the cause of death was a massive skull fracture.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

After an investigation that lasted more than two years, [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] was arrested and charged with the crime. In a trial that was held from January 2 to February 13, 1935, Hauptmann was found guilty of murder in the first degree and sentenced to death. He was executed by [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] at the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] on April 3, 1936. Hauptmann proclaimed his innocence to the end.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Newspaper writer [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] called the kidnapping and subsequent trial "the biggest story since the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]".[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.][You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] The crime spurred [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] to pass the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], commonly called the "Lindbergh Law", which made transporting a kidnapping victim across state lines a [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.].[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Not finding Charles Lindbergh Jr. with his mother, the nurse came down to talk with Mr. Lindbergh, who was in the library just below the baby's room in the southeast corner of the house. Charles Lindbergh went immediately to the child's room to see for himself that the baby was gone. As he searched the room, he found a white envelope on the window sill above the radiator.

Lindbergh took his gun and went around the house looking for intruders. In 20 minutes, the local police were on the way to the home, along with the media and the family's lawyer. Later that night, one tire print was discovered in the mud caused by the rainy weather conditions earlier that day. Shortly after the police had begun searching near the perimeter of the house, they discovered three pieces of a ladder in a nearby bush that appeared intelligently designed but crudely constructed.

After midnight, a fingerprint expert arrived at the home to examine the note left on the window sill and the ladder. The ladder had 400 partial fingerprints and some footprints left behind. However, most were of no value to the investigation due to the surge of media and police that were present within the first 30 to 60 minutes after the first call for help. During the fingerprint discovery process, not a single usable fingerprint was found in the room, none from Mr. and Mrs. Lindbergh, none from the baby, and none from Betty Gow. There were smudges found proving that the nursery was not wiped clean as suggested by some authors. Getting any solid evidence outside the house proved to be virtually impossible. The ransom note that was found by Lindbergh was opened and read by the police after they arrived. The brief, handwritten letter was riddled with spelling mistakes and grammatical irregularities:

Word of the kidnapping spread quickly, and, along with police, the well-connected and well-intentioned arrived at the Lindbergh estate. There were military colonels offering their aid, though only one had law enforcement expertise: [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. The other colonels were [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], a [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] lawyer; [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] (a.k.a. "Wild Bill" Donovan, a hero of the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] who would later head the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]). Lindbergh and these men believed that the kidnapping was perpetrated by organized crime figures. The letter, they thought, seemed written by someone who spoke German as his native language. Charles Lindbergh, at this time, used his influence to control the direction of the investigation.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

They contacted Mickey Rosner, a Broadway hanger-on rumored to know mobsters. Rosner, in turn, brought in two [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] owners: Salvatore "Salvy" Spitale and Irving Bitz. Lindbergh quickly endorsed the duo and appointed them his intermediaries to deal with the mob.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Several organized crime figures – notably [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], Willie Moretti, Joe Adonis and Longy Zwillman — spoke from prison, offering to help return the baby to his family in exchange for money or for legal favors. Specifically, Capone offered assistance in return for being released from prison under the pretense that his assistance would be more effective. This was quickly denied by the authorities.

The morning after the kidnapping, U.S. President [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] was notified of the crime. Though the case did not seem to have any grounds for federal involvement (kidnapping then being classified as a local crime), Hoover declared that he would "move Heaven and Earth" to recover the missing child. The [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] (not yet called the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]) was authorized to investigate the case, while the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] and the Washington, D.C., police were told their services might be required. New Jersey officials announced a $25,000 reward for the safe return of "Little Lindy". The Lindbergh family offered an additional $50,000 reward of their own. The total reward of $75,000 was made even more significant by the fact that the offer was made during the early days of the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.].

A few days after the kidnapping, a new ransom letter arrived at the Lindbergh home via the mail. Postmarked in [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], the letter was genuine, carrying the perforated red and blue marks.

A second ransom note then arrived by mail, also postmarked from Brooklyn. Then, a third letter was mailed. It too came from Brooklyn. This letter warned that since the police were now involved in the case, the ransom had been raised to $70,000.

On May 12, 1932, delivery truck driver William Allen pulled his truck to the side of a road about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of the Lindbergh home near the hamlet of [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] in neighboring Hopewell Township.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] He went to a grove of trees to relieve himself, and there he discovered the body of a toddler.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] Allen notified the police, who took the body to a morgue in nearby [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]. The body was badly decomposed, and it was discovered that the skull was badly fractured. The body looked like it had been chewed on and attacked by various animals as well as indications that someone had made an attempt to hastily bury the body.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.][You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] Lindbergh and Gow quickly identified the baby as the missing infant based on the overlapping toes of the right foot and the shirt that Gow had made for the baby. They surmised that the child had been killed by a blow to the head. Mr. Lindbergh was insistent on having the body cremated afterward.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Once the U.S. Congress learned that the child was dead, legislation was rushed making kidnapping a federal crime. The FBI could now aid the case more directly.

In June 1932, officials began to suspect an "inside job" perpetrated by someone the Lindberghs trusted. Suspicions fell upon Violet Sharp, a British household servant at the Morrow home. She had given contradictory testimony regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping. It was reported that she appeared nervous and suspicious when questioned.

She committed suicide on June 10, 1932,[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] by ingesting a silver polish that contained [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] just prior to what would have been her fourth time being questioned.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.][You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] After her alibi was confirmed, it was later determined that the possible threat of losing her job and the intense questioning had driven her to commit suicide. At the time, the police investigators were criticized for what some felt were the "heavy handed" police tactics used.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Following the death of Violet Sharp, John Condon was also questioned by police. Condon's home was searched as well, but nothing was found that tied Condon to the crime. Charles Lindbergh stood by Condon during this time as well

Erastus Mead Hudson was a fingerprint expert who knew the then-rare silver nitrate process of collecting fingerprints off wood and other surfaces on which the previous powder method could not detect fingerprints. He found that Hauptmann's fingerprints were not on the wood, even in places that the man who made the ladder would have had to touch. Upon reporting this to a police officer and stating that they must look further, the officer said, "Good God, don't tell us that, Doctor!" The ladder was then washed of all fingerprints, and Schwarzkopf refused to make it public that Hauptmann's prints were not on the ladder.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Several books have been written proclaiming Hauptmann's innocence. These books variously criticize the police for allowing the crime scenes to become contaminated, Lindbergh and his associates for interfering with the investigation, Hauptmann's trial lawyers for ineffectively representing him, and the reliability of the witnesses and the physical evidence presented at the trial. [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], in particular, questioned much of the evidence, such as the origin of the ladder and the testimony of many of the witnesses. A recent book on the case, A Talent to Deceive by British investigative writer William Norris, not only declares Hauptmann's innocence but also accuses Lindbergh of a cover-up of the killer's true identity. The book points the finger of blame at Dwight Morrow, Jr., Lindbergh's brother-in-law.[[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]] No proof is offered, however.

At least one modern author disagrees with these theories. Jim Fisher, a former FBI agent and professor at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania,[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] has written two books on the subject, The Lindbergh Case (1987)[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] and The Ghosts of Hopewell (1999)[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] to address, at least in part, what he calls a "revision movement" regarding the case.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] In these texts, he provides an interpretation discussing both the pros and cons of the evidence presented at trial. He summarizes his conclusions thus: "Today, the Lindbergh phenomena [[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]] is a giant hoax perpetrated by people who are taking advantage of an uninformed and cynical public. Notwithstanding all of the books, TV programs, and legal suits, Hauptmann is as guilty today as he was in 1932 when he kidnapped and killed the son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lindbergh."

In 2005, the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] television program [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] conducted a re-examination of the physical evidence in the kidnapping using more modern scientific techniques. Kelvin Keraga concluded that the ladder used in the kidnapping was made from wood that had previously been part of Hauptmann's attic. Three forensic document examiners, Grant Sperry, Gideon Epstein, and Peter E. Baier, PhD, worked independently of each other. Sperry concluded that it was "highly probable" that the kidnapper's notes were written by Hauptmann. Epstein concluded that "there was overwhelming evidence that the notes were written by one person and that one person was Richard Bruno Hauptmann.

Baier wrote that Hauptmann "probably" wrote the notes, but Baier said,"Looking at all these findings no definite and unambiguous conclusion can be drawn." The program concluded that Hauptmann had indeed been guilty but it noted that many questions remained, such as how he could have known that the Lindberghs would be remaining in Hopewell during the week.

Several authors have suggested that Charles Lindbergh, the father, was responsible for the kidnapping. In 2010, Jim Bahm, author of the book Beneath the Winter Sycamores about the Lindbergh Kidnapping, implied that the baby was physically disabled and Charles Lindbergh wanted to have someone else raise the child in Germany. In the book, after 10 days, the baby died of pneumonia, and the kidnapping plot blew up in Lindbergh's face.

Robert Zorn's 2012 book, Cemetery John, proposes that Hauptmann was the foot soldier in a conspiracy with two other German-born men, John and Walter Knoll. Zorn's father, economist Eugene Zorn, had been investigating an incident from his teen years that convinced him he had witnessed the conspiracy being discussed. After the elder Zorn's death, son Robert continued the investigation

The 2007 disappearance of a three-year-old Madeleine McCann from her bed in Portugal proved an instant, worldwide sensation. There's been nothing like it since America's Lindbergh kidnapping eighty years ago.

But what is this all about? It actually looks very interesting, and well worth a bit of research.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

The kidnapping of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., the son of famous aviator [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] and [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], was one of the most highly publicized crimes of the 20th century. The 20-month-old toddler was abducted from his family home in [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], on the evening of March 1, 1932.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] Over two months later, on May 12, 1932, his body was discovered a short distance from the Lindberghs' home in neighboring [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.].[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] A medical examination determined that the cause of death was a massive skull fracture.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

After an investigation that lasted more than two years, [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] was arrested and charged with the crime. In a trial that was held from January 2 to February 13, 1935, Hauptmann was found guilty of murder in the first degree and sentenced to death. He was executed by [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] at the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] on April 3, 1936. Hauptmann proclaimed his innocence to the end.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Newspaper writer [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] called the kidnapping and subsequent trial "the biggest story since the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]".[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.][You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] The crime spurred [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] to pass the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], commonly called the "Lindbergh Law", which made transporting a kidnapping victim across state lines a [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.].[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

The crime[[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]]

At 8:00 PM on the 1st of March 1932, Betty Gow, the nurse of the family, put Charles Lindbergh Jr., then 20 months old, to bed in his crib. She wrapped the baby in a blanket and fastened it with two large pins to prevent him from moving during sleep. Around 9:30 PM, Charles Lindbergh Sr., the baby's father, heard a noise that made him think that the slats from the full orange crate in the kitchen had broken off and fallen. However, at 10:00 PM, Betty Gow returned to the baby's bedroom to discover that he was not in his crib. She asked Mrs. Lindbergh, who had just come out of her bath, if the baby was with her.Not finding Charles Lindbergh Jr. with his mother, the nurse came down to talk with Mr. Lindbergh, who was in the library just below the baby's room in the southeast corner of the house. Charles Lindbergh went immediately to the child's room to see for himself that the baby was gone. As he searched the room, he found a white envelope on the window sill above the radiator.

Lindbergh took his gun and went around the house looking for intruders. In 20 minutes, the local police were on the way to the home, along with the media and the family's lawyer. Later that night, one tire print was discovered in the mud caused by the rainy weather conditions earlier that day. Shortly after the police had begun searching near the perimeter of the house, they discovered three pieces of a ladder in a nearby bush that appeared intelligently designed but crudely constructed.

The investigation[[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]]

First on the scene was Chief Harry Wolfe of the nearby [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] police. Wolfe was soon joined by [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] officers. The police searched the home and scoured the surrounding area for miles.After midnight, a fingerprint expert arrived at the home to examine the note left on the window sill and the ladder. The ladder had 400 partial fingerprints and some footprints left behind. However, most were of no value to the investigation due to the surge of media and police that were present within the first 30 to 60 minutes after the first call for help. During the fingerprint discovery process, not a single usable fingerprint was found in the room, none from Mr. and Mrs. Lindbergh, none from the baby, and none from Betty Gow. There were smudges found proving that the nursery was not wiped clean as suggested by some authors. Getting any solid evidence outside the house proved to be virtually impossible. The ransom note that was found by Lindbergh was opened and read by the police after they arrived. The brief, handwritten letter was riddled with spelling mistakes and grammatical irregularities:

Word of the kidnapping spread quickly, and, along with police, the well-connected and well-intentioned arrived at the Lindbergh estate. There were military colonels offering their aid, though only one had law enforcement expertise: [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. The other colonels were [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], a [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] lawyer; [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] (a.k.a. "Wild Bill" Donovan, a hero of the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] who would later head the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]). Lindbergh and these men believed that the kidnapping was perpetrated by organized crime figures. The letter, they thought, seemed written by someone who spoke German as his native language. Charles Lindbergh, at this time, used his influence to control the direction of the investigation.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

They contacted Mickey Rosner, a Broadway hanger-on rumored to know mobsters. Rosner, in turn, brought in two [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] owners: Salvatore "Salvy" Spitale and Irving Bitz. Lindbergh quickly endorsed the duo and appointed them his intermediaries to deal with the mob.

[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Several organized crime figures – notably [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], Willie Moretti, Joe Adonis and Longy Zwillman — spoke from prison, offering to help return the baby to his family in exchange for money or for legal favors. Specifically, Capone offered assistance in return for being released from prison under the pretense that his assistance would be more effective. This was quickly denied by the authorities.

The morning after the kidnapping, U.S. President [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] was notified of the crime. Though the case did not seem to have any grounds for federal involvement (kidnapping then being classified as a local crime), Hoover declared that he would "move Heaven and Earth" to recover the missing child. The [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] (not yet called the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]) was authorized to investigate the case, while the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] and the Washington, D.C., police were told their services might be required. New Jersey officials announced a $25,000 reward for the safe return of "Little Lindy". The Lindbergh family offered an additional $50,000 reward of their own. The total reward of $75,000 was made even more significant by the fact that the offer was made during the early days of the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.].

A few days after the kidnapping, a new ransom letter arrived at the Lindbergh home via the mail. Postmarked in [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], the letter was genuine, carrying the perforated red and blue marks.

A second ransom note then arrived by mail, also postmarked from Brooklyn. Then, a third letter was mailed. It too came from Brooklyn. This letter warned that since the police were now involved in the case, the ransom had been raised to $70,000.

Discovery of the body[[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]]

On May 12, 1932, delivery truck driver William Allen pulled his truck to the side of a road about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of the Lindbergh home near the hamlet of [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] in neighboring Hopewell Township.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] He went to a grove of trees to relieve himself, and there he discovered the body of a toddler.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] Allen notified the police, who took the body to a morgue in nearby [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]. The body was badly decomposed, and it was discovered that the skull was badly fractured. The body looked like it had been chewed on and attacked by various animals as well as indications that someone had made an attempt to hastily bury the body.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.][You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] Lindbergh and Gow quickly identified the baby as the missing infant based on the overlapping toes of the right foot and the shirt that Gow had made for the baby. They surmised that the child had been killed by a blow to the head. Mr. Lindbergh was insistent on having the body cremated afterward.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Once the U.S. Congress learned that the child was dead, legislation was rushed making kidnapping a federal crime. The FBI could now aid the case more directly.

In June 1932, officials began to suspect an "inside job" perpetrated by someone the Lindberghs trusted. Suspicions fell upon Violet Sharp, a British household servant at the Morrow home. She had given contradictory testimony regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping. It was reported that she appeared nervous and suspicious when questioned.

She committed suicide on June 10, 1932,[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] by ingesting a silver polish that contained [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] just prior to what would have been her fourth time being questioned.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.][You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] After her alibi was confirmed, it was later determined that the possible threat of losing her job and the intense questioning had driven her to commit suicide. At the time, the police investigators were criticized for what some felt were the "heavy handed" police tactics used.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Following the death of Violet Sharp, John Condon was also questioned by police. Condon's home was searched as well, but nothing was found that tied Condon to the crime. Charles Lindbergh stood by Condon during this time as well

Review of the evidence

Erastus Mead Hudson was a fingerprint expert who knew the then-rare silver nitrate process of collecting fingerprints off wood and other surfaces on which the previous powder method could not detect fingerprints. He found that Hauptmann's fingerprints were not on the wood, even in places that the man who made the ladder would have had to touch. Upon reporting this to a police officer and stating that they must look further, the officer said, "Good God, don't tell us that, Doctor!" The ladder was then washed of all fingerprints, and Schwarzkopf refused to make it public that Hauptmann's prints were not on the ladder.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]

Several books have been written proclaiming Hauptmann's innocence. These books variously criticize the police for allowing the crime scenes to become contaminated, Lindbergh and his associates for interfering with the investigation, Hauptmann's trial lawyers for ineffectively representing him, and the reliability of the witnesses and the physical evidence presented at the trial. [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.], in particular, questioned much of the evidence, such as the origin of the ladder and the testimony of many of the witnesses. A recent book on the case, A Talent to Deceive by British investigative writer William Norris, not only declares Hauptmann's innocence but also accuses Lindbergh of a cover-up of the killer's true identity. The book points the finger of blame at Dwight Morrow, Jr., Lindbergh's brother-in-law.[[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]] No proof is offered, however.

At least one modern author disagrees with these theories. Jim Fisher, a former FBI agent and professor at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania,[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] has written two books on the subject, The Lindbergh Case (1987)[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] and The Ghosts of Hopewell (1999)[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] to address, at least in part, what he calls a "revision movement" regarding the case.[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] In these texts, he provides an interpretation discussing both the pros and cons of the evidence presented at trial. He summarizes his conclusions thus: "Today, the Lindbergh phenomena [[You must be registered and logged in to see this link.]] is a giant hoax perpetrated by people who are taking advantage of an uninformed and cynical public. Notwithstanding all of the books, TV programs, and legal suits, Hauptmann is as guilty today as he was in 1932 when he kidnapped and killed the son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lindbergh."

In 2005, the [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] television program [You must be registered and logged in to see this link.] conducted a re-examination of the physical evidence in the kidnapping using more modern scientific techniques. Kelvin Keraga concluded that the ladder used in the kidnapping was made from wood that had previously been part of Hauptmann's attic. Three forensic document examiners, Grant Sperry, Gideon Epstein, and Peter E. Baier, PhD, worked independently of each other. Sperry concluded that it was "highly probable" that the kidnapper's notes were written by Hauptmann. Epstein concluded that "there was overwhelming evidence that the notes were written by one person and that one person was Richard Bruno Hauptmann.

Baier wrote that Hauptmann "probably" wrote the notes, but Baier said,"Looking at all these findings no definite and unambiguous conclusion can be drawn." The program concluded that Hauptmann had indeed been guilty but it noted that many questions remained, such as how he could have known that the Lindberghs would be remaining in Hopewell during the week.

Several authors have suggested that Charles Lindbergh, the father, was responsible for the kidnapping. In 2010, Jim Bahm, author of the book Beneath the Winter Sycamores about the Lindbergh Kidnapping, implied that the baby was physically disabled and Charles Lindbergh wanted to have someone else raise the child in Germany. In the book, after 10 days, the baby died of pneumonia, and the kidnapping plot blew up in Lindbergh's face.

Robert Zorn's 2012 book, Cemetery John, proposes that Hauptmann was the foot soldier in a conspiracy with two other German-born men, John and Walter Knoll. Zorn's father, economist Eugene Zorn, had been investigating an incident from his teen years that convinced him he had witnessed the conspiracy being discussed. After the elder Zorn's death, son Robert continued the investigation

Similar topics

Similar topics» 'Anti-McCann' websites plotted to kidnap one of Madeleine's siblings - Daily Mail INCLUDES TWEETS FROM JERRY LAWTON RE MICHAEL WRIGHT TESTIMONY

» Sunday Express - Is this the moment of Madeleine McCann's kidnapping?

» Express today - is this the moment of Madeleine McCann's kidnapping

» Baby Siwaphiwe's mother arrested for FAKE kidnapping

» Dad ‘killed baby son, then faked kidnapping to cover-up the killing’

» Sunday Express - Is this the moment of Madeleine McCann's kidnapping?

» Express today - is this the moment of Madeleine McCann's kidnapping

» Baby Siwaphiwe's mother arrested for FAKE kidnapping

» Dad ‘killed baby son, then faked kidnapping to cover-up the killing’

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum